Save

UX is a relatively nascent discipline: a boisterous, hopeful, opinionated, and insightful young adult who sometimes lacks perspective.

Need evidence? Just yesterday personas were a UX designers’ BFF, but today? Well, not so much.

There’s been some gossip about how they are ‘fakes’ and really don’t help build empathy.

Some have even called for their total abandonment. What’s behind this trajectory from love to hate? Is there hope for personas as real empathy builders?

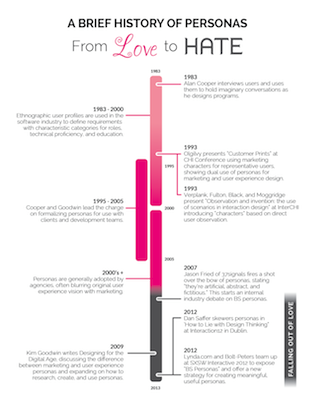

A Brief History of Personas

30 years ago, Alan Cooper talked with actual software users and leveraged the insights from these conversations when designing user interfaces. This was the birthplace of personas as we known them. Recalling these people’s traits, characteristics, and abilities helped Cooper imagine their responses to his design ideas. (Click timeline for full-sized image.)

Other creatives joined in. In 1993 Olgilvy wrote about “Customer Prints,” using marketing characteristics for representative users. That same year, Verplank, Fulton, Black, and Moggridge presented “Observation and Invention: the use of scenarios in interaction design” at InterCHI which introduced “characters” based on direct user observation.

Over the next 10 years, Cooper, Kim Goodwin, and others wrote about personas and how to create them. The software industry adopted personas slowly: first the pioneering HCI folks took interest, then forward-thinking agencies picked them up as a way to understand users. Personas spread as an integral way of representing users during the design and development process.

Problems in Personaland

As their use spread, the distinction between marketing and UX personas blurred, for several reasons. This blurring sowed seeds of discontent around personas that erupted in the maturing UX world in 2007, calling into question personas’ purpose and usefulness. Here’s what happened:

Half-Baked Personas

Early persona-adopter designers and researchers soon learned how hard it was to sell design research both within an organization and to outside clients. Research can be expensive, it’s hard to show immediate ROI, and it takes precious time at the beginning of the design and development process.

This led to the first type of problem persona: the half-baked persona. Research was gathered as it was possible—maybe instead of getting 15 contextual inquiries, five user interviews were performed. Or, if that wasn’t possible, two quick phone interviews and a reliance on available marketing data.

These personas weren’t entirely made up, but they weren’t built on a wealth of first-hand user research. It was easy to produce deceivingly authoritative personas based on this thin information. Details pulled from the consumer studies available were used and embellished upon. Assumptions were made and logos were pasted under “Brand Affinities.” Designers wanted the feeling of having rich personas, but they didn’t have the design research findings to back them up.

Empty Personas

Worse than the half-baked persona is the second type of problem persona: the truly fictional one. Based only on marketing data or the opinions of company stakeholders, whether they’d ever met a real user or not, fictional personas poisoned the pool.

They had no grounding in direct user research, were usually drenched in superfluous details, and they could be smelled from across the office. When presented with a fictional persona, product development teams usually take one look, smile sadly, nod, and get on with their business. And so, the hatred of “BS personas” was born.

Looking for the Fix

Even if designers are able to get funding for their coveted research, there are still problems. When creating personas, it’s easy to take shortcuts during analysis and the personas wrung out of it are shoved into user categories that are irrelevant to the current design problem.

These personas are often too specific, focusing on traits that don’t inform design decisions. For example, when redesigning customer support tracking software, do we need to know if Customer Service Sue is married or single? Isn’t it more important that first-hand user research surfaces insights that not all support reps seem to have the same motivations? Inexperienced reps are focused on their performance numbers—the number of tickets they can close in a day—while experienced reps pay little attention to their stats: they are confident about their performance and instead focus on providing great customer service. These are the sorts of revelations that can lead to real innovation.

How to Get Back to that Loving Feeling

Good personas that enable us to have extended role-play with our users serve a need that isn’t currently filled by anything else. If the design community throws personas in the trash, they’re back to square one: the standard old argument around the product team table based on everyone’s personal opinion. The user is lost in the equation.

So, how can we get back the persona love?

Get Grounded

Good, solid first-person research is at the heart of all useful personas. This includes careful preparation and participant recruiting across a wide variety of potential users. The resulting observations require thoughtful, creative analysis and synthesis that not only boils down what the users are doing and expressing but finds out why: why is this observation true?

While design researchers advocating best practices have encouraged the addition of personal details to make personas feel more real, Jonathan Grundin wrote about how traits change and that personas should focus on goals, motivations, and expectations. This is especially true when real users switch personas as their context changes. Tying personas to personal characteristics and preferences doesn’t help us in these situations, it distracts us. There’s a fine balance between the goals/motivation/expectation focus and the information that increases the humanity of our personas. This balance must be struck carefully for each design problem—each time personas are sussed out of our messy set of user data.

The resulting personas are the opposite of BS. Real personas get at the core, using the users’ own words heard during research. Real personas are not made in some cookie-cutter template but have morphed and changed through the analysis process to reflect the situation and mindset of a particular user group.

The role-playing conversation held with these motivated characters—whether through scenarios, storyboards, or in discussions—is used to make decisions on feature prioritization and to craft usable designs. The personas talk back. A persona can say, “I don’t care about that. This is what’s important to me.”

Round Out with Real Voices

The presentation of personas should facilitate a deep understanding as well as the ability to scan, parse, and leverage information. Placemat personas are often looked at once and put away forever. Don’t consign your poor users to this fate: there must be an effective vehicle for sharing research findings about targeted end users.

If direct research can be shared, allow actual users to tell their own stories. Use real photos, audio, or video of people in their environment. Instead of inventing stories to bring imaginary people to life, lean on journalistic or documentary techniques to let users have their say in their own words. See how The New York Times lets a woman speak for herself.

User researchers can employ similar methods, bringing together users with similar goals or motivations to tell a collective story. It will be far more memorable to a development team to hear four interviewees describe a goal in similar terms than to scan a single PDF that gets filed away. If the entire team believes in the personas and who they represent, personas are much more likely to be loved and used.

Evangelize Your Personas

Beyond letting the personas speak through real users’ voices, they can be kept alive within an organization by laying some groundwork.

- Name and empower an internal champion to keep personas alive and involved in the process.

- Create persona signifiers for continued use throughout the organization. Despite sometimes feeling goofy, we’ve found giving personas memorable names helps them stick in team member’s minds.

- Create cardboard cutouts, photos, or hats with the personas’ names on them to use when speaking with their voice.

- Present personas to key departments and even the entire company.

- Pair personas with visual storyboards and scenarios as design moves forward.

- Use role-playing and Q&A with personas to answer questions the team has. This helps establish a “culture of asking” instead of making things up based on hearsay or personal opinions in the team.

Conclusion

These steps—solid research, creative analysis, and compelling presentation and rollout—can bring teams back around to a tool that they badly need. Feel free to dump the shallow personas that people roll their eyes at. It’s time to reengage with empathetic work by making your users real, and letting their real voices be heard.

Timeline graphic by Oscar Tellez

Image of hand heart courtesy Shuttertock

- Analytics and Tracking, Business Value and ROI, Contextual User Studies, Customer Experience, Design, Design Tools and Software, Development, Direct Observation Research, Human factors, Information Design and Architecture, Interaction Design, Interface and Navigation Design, Internal Company Dynamics, Marketing and Brand, Personas, Product design, Psychology and Human Behavior, Research Methods and Techniques, Research Tools and Software, Storytelling, Strategy, Usability, User Acceptance Testing, User Adoption, User Reported Feedback, Working With Stakeholders

Kyra Edeker

As principal UX designer for projekt202, Kyra finds joy in taking the initial chaotic soup of requirements, user data, and expectations and distilling it with a goal in mind: to create elegant interfaces and services that makes users' lives better. Kyra has worked with large companies including PayPal, Motorola, Microsoft, and Charles Schwab, as well as startups, non-profits and universities. With all of them she has found that user research makes a positive difference in how teams work together to make successful products.

Jan Moorman

As principal design researcher for projekt202, Jan is responsible for both generative and evaluative user research. Figuring out how to answer design questions demands creativity and willingness to experiment with methods. Her passion for research lies in her fundamental belief that design research can lead to nonobvious insights. She pulls ideas from a diverse set of experiences and industries. Her background and work experience wander from science to art and back. She holds degrees in Fine Art and Computer Science. She has worked in analytical chemistry, software architecture, scientific visualization, performance support and interface design. She believes that the skill of research cannot be completely learned from textbooks and is excited about having the opportunity to mentor and coach students at Austin Center for Design.