The products we design often change people’s daily behaviors and routines. Not just in the sleazy manipulative ways associated with slick advertising, but in ways that help users take actions they want to take, but struggle with: from exercising more to organizing their inbox. Good UX and UI practices have long focused on how to enable users to take action by removing frictions, making decisions less complex, etc.

Over the last few years, however, we’ve learned more about how the mind makes decisions, which has given us new tools to support action. We’ve seen an explosion of research in behavioral economics with popular books like Nudge, Predictably Irrational, or Blink talking about the heuristics our minds use when confronting complex problems. These build on older traditions in persuasive design and the psychology of judgment and decision making. At the same time, a wave of new technologies is encouraging people to change behavior from Jawbone Up (exercise) to Nest (energy usage) to HelloWallet (personal finance).

I’m a behavioral social scientist, and for the last few years I’ve had the privilege of working with leading researchers around the country, and interviewing dozens of companies in this space to understand how they’re applying behavioral research. I recently wrote a book called Designing for Behavior Change, which codifies key lessons from researchers and practitioners in the field, and provides give step-by-step guidance on how to apply behavioral economics and psychology to product design.

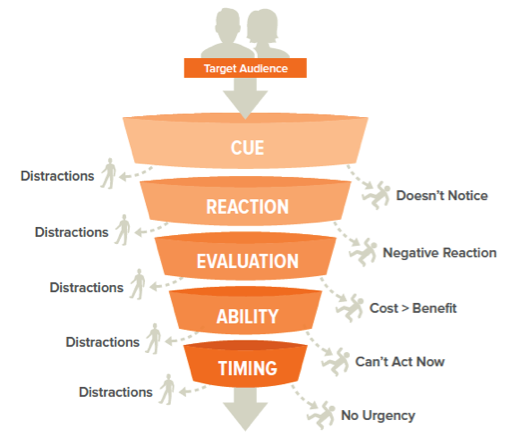

One way that I’ve found to organize and apply the research literature is to think about the preconditions for action: what needs to come together at the moment a user takes action. For example, before the user’s conscious mind starts thinking about taking action, the mind’s automatic and intuitive processing system will react (what psychologists call “System 1” in Dual Process Theory), providing an immediate assessment of whether or not the action is relevant and whether it’s good or bad. There are five such preconditions that need to come together before a user takes action.

Five preconditions for action

Let’s say you’ve developed a new app that helps people exercise more, like RunKeeper or Moves. Imagine one hundred people sitting on their couches, watching TV. They’ve previously downloaded your app onto their phones but when and why would they suddenly get up, load your app, and go for a run?

We assume that somehow users find us, love what we’re doing, and use our products whenever they want

We don’t often think about user behavior in this way. We assume that somehow users find us, love what we’re doing, and use our products whenever they want to. But, behavioral researchers have learned that there’s more to it than that. So, imagine 100 people sitting on 100 couches. What needs to happen for them to use your app right now?

- Cue: Something needs to cue them to think about it. The possibility of going running needs to somehow cross their mind. Maybe a push notification, an SMS invite from a friend, or an ad on TV.

- Reaction: Once cued, the mind will automatically react to the idea, intuitively and emotionally. What do your users think about running? For some, it’s great; for others it’s new and strange. Others still might be embarrassed about being out of shape.

- Evaluation. With conscious awareness, the mind will do a quick cost-benefit analysis. How hard will it be to do, what’s the value for them, what else could they do with their time, etc.? For some people, running is a net negative (maybe it aggravates a knee condition) and for others, it’s great.

- Ability. The person must actually be able to act and know it. The person must know logistically what to do, and have the resources and self-confidence to do it. Some users may not have running shoes, for others it’s raining outside: they can’t run even though they wanted to.

- Timing. The person needs to have a reason to act now, rather than doing something else that’s more urgent. Maybe the user wants to run, but is busy watching TV and procrastinates.

These five things—cue, reaction, evaluation, ability, and timing—are preconditions for executing the action (they also loosely spell the acronym “CREATE,” which is handy since that’s what’s needed to create action). You can think of them as “tests” that any action must pass: all must complete successfully in order for your user to consciously, intentionally, engage in the action: whether it be running or posting a photo online.

The Funnel to CREATE Action is Leaky

You can think about these five tests as a leaky funnel, with two holes in each stage. On one side, people can reject the action because it’s not valuable enough, it’s not urgent, etc. On the other side, they can get distracted and do something else (like answering the phone).

For habitual actions, the process is mercifully shorter because the mind is on auto-pilot, but there’s a catch: People have to choose to do something again and again before it can become a habit. Authors and researchers such as Charles Duhigg, Nir Eyal, and Wendy Wood have done great work exploring how habits function, but you can’t get around the basic problem of choosing to build the habit in the first place. And that takes the five preconditions outlined above.

So How We Can Support Action?

To help users take action, whether it be learning how to use your website or stating to eat healthier, we need to do two things.

- We need design our products to ensure that these five preconditions are met. That includes thinking strategically about how users will interact with the product, ensuring there is a clear call to action, providing urgency, and building up the user’s self-confidence in their ability to act, where needed.

- We need to find the big holes in the funnel and plug them. That means figuring out whether users never even think about the action (a cue problem), if it’s too much of a pain in the butt (evaluation problem) or if they lack urgency (a timing problem).

While there are powerful techniques that can help users overcome behavioral obstacles (e.g., peer comparisons, leveraging loss aversion, careful framing, and priming effects) there’s no secret trick to suddenly “make” people act the way you want them to (anyone that tells you differently is trying to sell you something). Instead, good UX design—based on a deep understanding of the particular needs and challenges your users face, and supported by behavioral tools such as these—can find the right solutions for specific situations.

Image of sprinter leaving starting blocks courtesy Shutterstock.