Save

Empathy has become a buzzword.

It’s generally a good idea to be weary of buzzwords. Empathy is no exception.

My first encounter with the word was more than 10 years ago. I was a few years out of college and a close friend was suffering from bipolar depression. Out of a sincere desire to help, I sought out a psychiatrist.

At our first meeting, the psychiatrist recommended I empathize with my friend. I asked her how, and she requested that I first learn to listen. “Listen?” I asked myself. “I surely know how to do that already!” I thought to myself.

I was wrong.

Turns out, I had mistook “listening” with mere perception. I thought what constituted “listening,” was the act of paying attention to what others were saying without interrupting them.

This was not the case.

Perception was insufficient without appropriate interpretation and inquiry.

Let me illustrate this point by sharing an excerpt from my book, Realizing Empathy: An Inquiry into the meaning of Making, describing an experience I had with woodworking:

The sun is shining through the floor-to-ceiling windows of the woodshop. I am standing across a tall piece of wood, clamped to the workbench. I hear mallets banging and clamps clanging, as I move my Japanese saw back and forth, along the top of the wood, hoping to cut out a couple notches for joinery.

I am in the zone, guiding the saw, shooting for a straight line, until I notice an instructor standing all the way across the room, staring at me in perfect stillness.

“Yes?” I look up, feeling self-conscious.

“You know…” The instructor responds, as I stand upright to hear his next words. “If you listen, the wood will tell you how you’re doing. It is very honest.” I stand staring, unsure of how to interpret his Zen master-like comment. “Do it again,” the instructor suggests, as he starts to walk toward me. “And this time, listen.”

I lean over and start to saw, as I take note of the sound of the blade rubbing against the wood.

I hear nothing of significance.

“Now…” The instructor interrupts, as he reaches in, unclamps the wood, lowers it, and clamps it again. Less than two inches of the tall piece of wood is now revealed above the workbench. “Try again. And listen carefully.”

I reposition my saw, and slowly start to move it back and forth, quickly, establishing a steady rhythm.

And then I hear it.

Or should I say I don’t hear it. The rumbling noise, that is. I guess it was a rumbling noise. I am now thinking in hindsight. With the noise gone, all I am left with is what sounds like my teeth biting into an apple.

“Oh wow! I hear it now. That’s amazing!” I blurt out in awe in the absence of sound.

In retrospect, the moment he lowered the wood, I should have realized what I had done. I had clamped the wood too high, allowing it to vibrate, making a noise similar to that of a heavy piece of furniture being dragged across the floor.

The instructor was right.

The wood was being honest.

But until now, I was not listening.

Or more precisely, I heard the sound, but I was so busy trying to get the wood to saw straight, that I didn’t try to understand what the sound meant. Or worse yet, I assumed I did, because I thought the sound of sawing was, well … the sound of sawing. That if there could be any differences in sound, that they were meaningless. When in fact, they were meaningless because I didn’t think they could be different. And because I didn’t think they could be different, I didn’t care enough to listen. And without listening, I could perceive no differences, leaving behind an echo of wasted honesty.

The signals we perceive from “others,” be it human beings or a piece of wood, are often interpreted in the context most immediately available to our minds. That context, however, is one of many different contexts with which that signal can be interpreted.

Have you ever read a book as a teenager then read it again as an adult? Were you surprised at how you had missed the so-called “hidden meanings” now in “plain sight?” If so, that’s in large part because you have developed a broader and more nuanced choices of context with which to interpret the book’s content. In an interview captured inside Realizing Empathy, Dr. Lewis Lipsitt, one of the pioneers of child psychology at Brown University, refers to this process as maturation. It’s a phenomenon where what we once assumed to know takes on more subtlety and nuance, thus changes in meaning.

What we once assumed to know takes on more subtlety and nuance, thus changes in meaning.

In much the same way, the woodworking instructor helped me mature by empowering me to learn a new choice of context. One with which I could reinterpret the signals I were perceiving. One with which I could experience and understand the signals differently from before. Without such context coupled with my lack of inquiry, the signals I were perceiving from my sawing could mean nothing more to me than merely an abstract symbol for “the sound of sawing.” I speak more in depth about this topic in the following TEDx talk:

In this talk, I share the story of how unaware I was of my lack of empathy in relation to a piece of wood, my friend, and my professional colleague.

Clarifying Empathy

In the mainstream media, it’s become fashionable to talk about empathy as being about reading people minds or feeling what they are feeling. While this framing is understandable, it comes with the danger of confusing the means with the ends.

The word “empathy” is a translation of a German word “einfühlung.” Einfühlung was a word invented to explain how it is that people can come to experience a sense of unity (often referred to as “oneness”) with a piece of art work. It describes an experience where the boundary between the objectified “self” and “other” blurs without completely disappearing. A metaphor often used to describe the experience was an “entering into” an art object, be it a painting, a sculpture, a novel, or a performance. The metaphor is still used to this day when we speak of “stepping into” other people’s shoes.

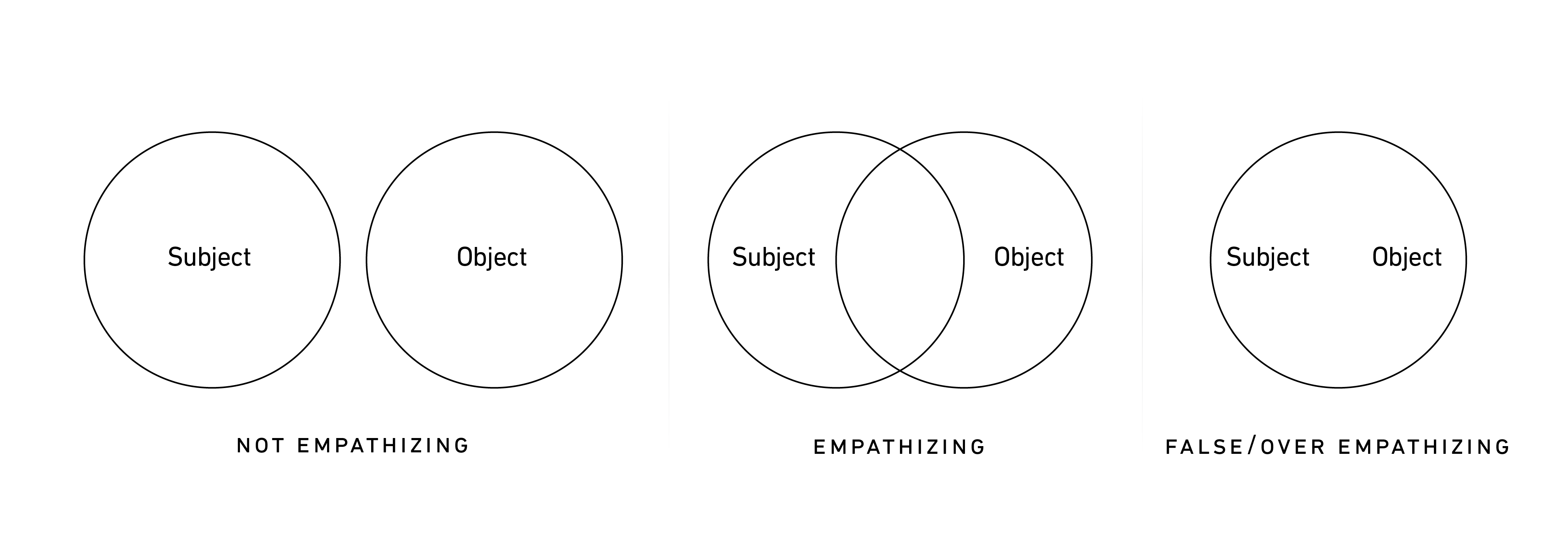

There are three distinct states to note when it comes to empathizing. They are always in relation to an “other.” Not empathizing is when you do not feel a sense of unity with that ”other.” Empathizing is when you do. False or over empathizing is when you confuse your “self” with that “other.” This can often feel overwhelming and unpleasant.

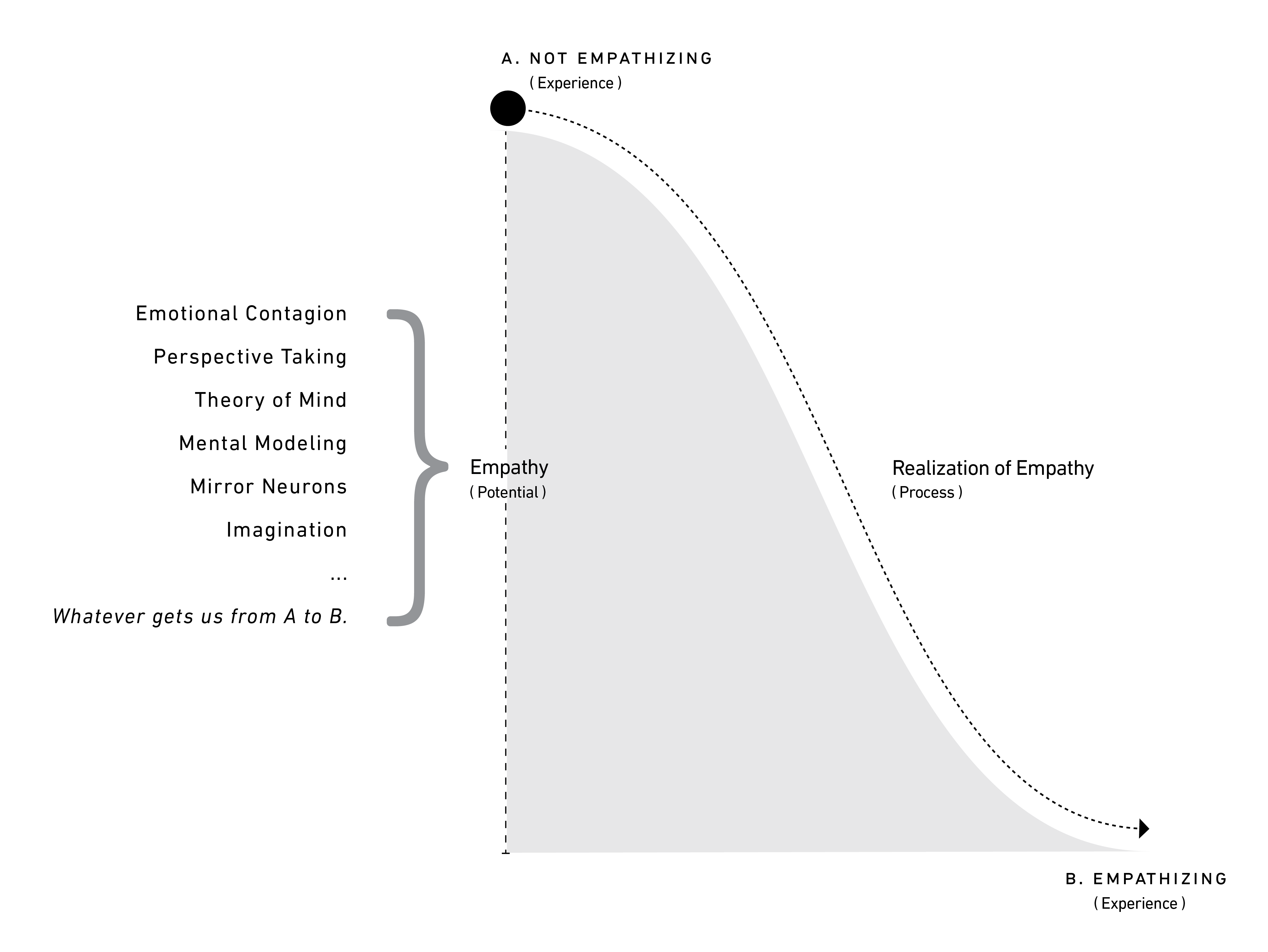

If empathy is a word invented to explain how it is we go from not experiencing a sense of unity with an “other” to experiencing it, reading people’s minds (known as perspective taking or theory of mind) or feeling what they are feeling (known as emotional contagion) may indeed be useful and sometimes even necessary abilities in this journey. Nonetheless, however, they are means to an end. An end signified by the experience of unity.

Imagine rolling a ball down hill. Empathy is a word invented to refer to the potential we have at the top of the hill. Empathizing is an experience that happens when the ball reaches the bottom of the hill. in any interaction with an “other”—be it a person, a piece of wood, or an art work—empathy can take us from “not empathizing” (not experiencing a sense of unity) to “empathizing” (experiencing a sense of unity). There are numerous components to empathy, which scientists are actively debating as we speak.

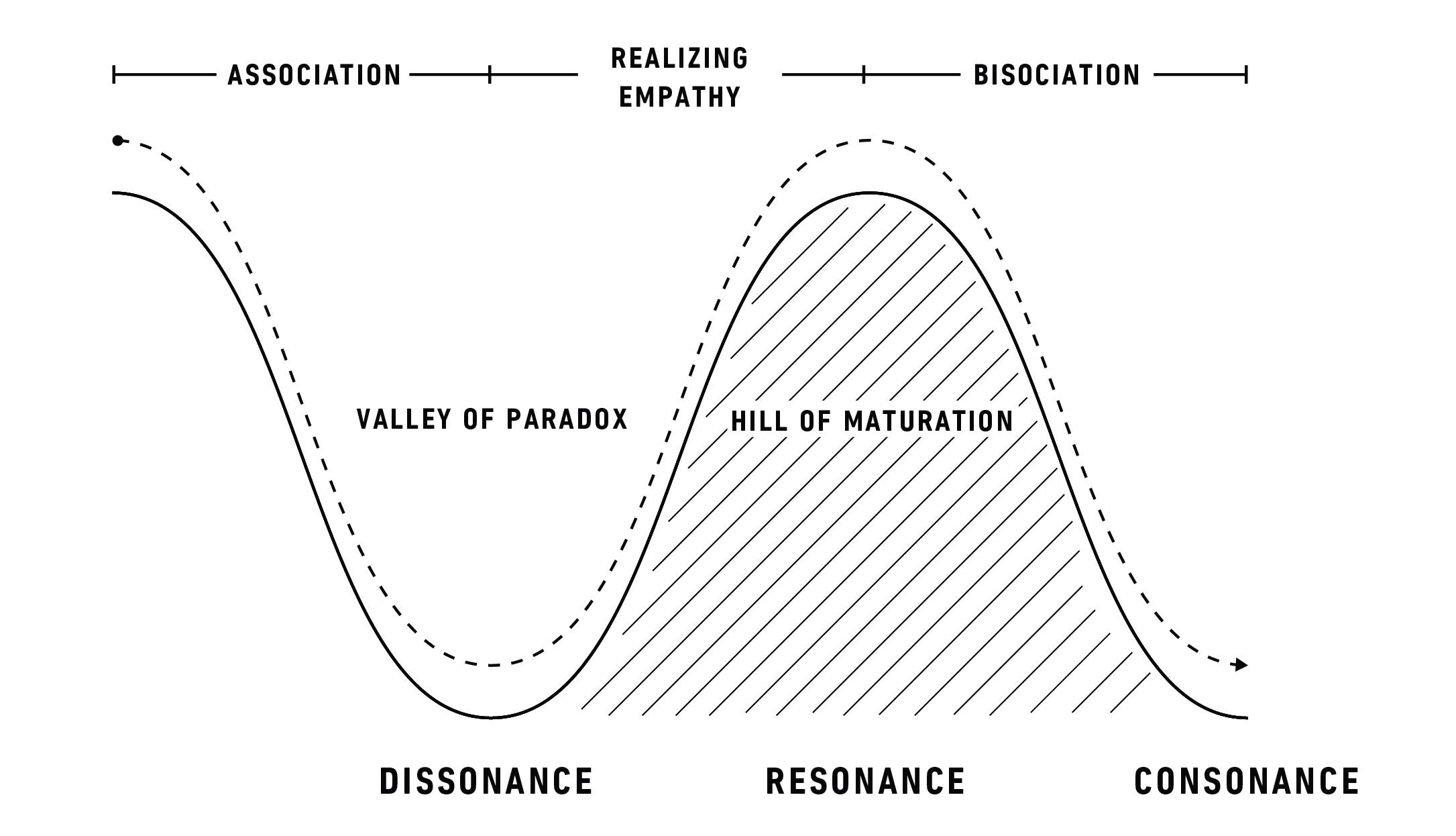

Sometimes empathy realizes “for” us involuntarily and passively. For example, many of us often empathize with fictional characters in this way while watching a film or reading a novel. However, empathy doesn’t always realize this way. Remember a time when you were faced with someone you thought of as being “stupid,” “wrong,” or even “evil.” In these cases empathy will not realize involuntarily.

In Realizing Empathy, I compare the process of making art with the process of coming to empathize with people. I argue that one of the main blocks to our empathy realizing involuntarily is a paradox: a conflict between reality and what our expectation of what reality should be. I also coin the phrase “realizing empathy” to refer to the process of facing an “other” we do not or cannot empathize with, then deliberately developing and practicing the means to do so.

When we encounter an “other” we cannot empathize with, we are at the bottom of a valley, which we have to climb up from, should we wish to empathize with them. I call this process “realizing empathy.” One of the major byproducts of this process is maturation.

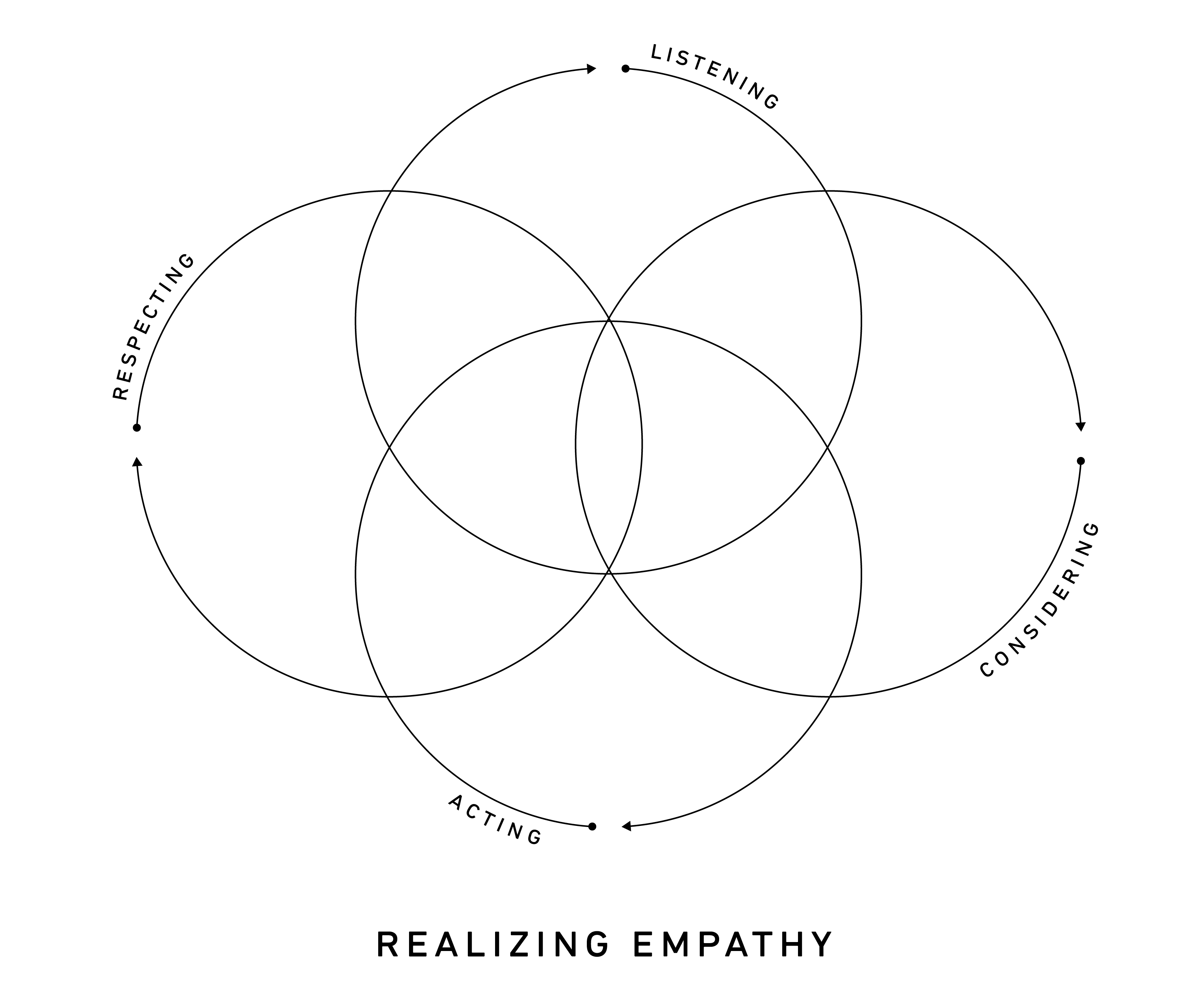

In articulating the practice of realizing empathy, I identify four integrated processes, one of which is the aforementioned “listening.”

Zooming into the process of “realizing empathy,” there are actually four inter-related yet distinct processes that has to work together to make this process possible.

The Role of Empathy in Design

In the design community, we often use the word empathy as if it’s a tool used for acquiring insights. We talk about interviewing, observing, role-playing, or otherwise finding a way to gather knowledge from users to produce better products. This framing is especially valuable in differentiating our human-centered approach from those that care less about user input or participation. However, it’s also unnecessarily limiting and may sometimes even be unethical.

First of all, empathy need not be limited to users. It can apply to our clients. It can apply to our co-workers. It can apply to the materials we use to design and make with. In fact, it can even apply to our so-called “selves.” You may have said to yourself from time to time “I don’t feel like myself today,” or “I don’t really understand myself.” These situations can be thought of as indications of our inability to empathize with our objectified “selves.” Basically, empathy can apply to any object of our perception—whether the object is tangible or not. Seen in this fashion, our work designing products and services is realizing empathy with and across a variety of “others” in an integrated way. In other words, what we call products and services are byproducts of realizing empathy.

Second, insight is better framed as a byproduct of realizing empathy, not the goal. Focusing on acquiring insights or any kind of knowledge from others can turn empathy into a mere tool. If we’re not careful, this can negatively affect the quality of our interactions with “others.” There are differences between interrogation and interview, between understanding to manipulate/take advantage of and understanding to support. On the surface they seem like radically different activities, but once you get deep into it, you start to realize that it is really a fine qualitative line created by the focus and intent of the interaction.

Third, understanding is only one of the ways in which we can get to empathize with “others.” Another way is to simply be in flow with them: to feel a sense of unity with them over a prolonged duration of time. In this case, there need not be any pre-determined goal besides being curious where the interaction may lead us, enough to want to sustain it. This is desired when we want to engage our co-workers to come up with new or unexpected ideas, when we engage our materials to make something new or unexpected, or when we simply want to be present with someone doing much of nothing.

Fourth, once you realize that empathy need not be limited to users and move past the notion of “understanding” as the only way to empathize with others, you’ll start to notice that empathy is not merely about receiving, but also about giving. There are those who wish to frame empathy as lacking in action. This may be valid on a case-by-case basis, but it is not intrinsically true. When I look back at the various areas of art I explored while researching empathy (i.e. acting, dancing, drawing, sculpting, carpentry, etc…) this becomes abundantly clear. Acting, for example, is both empathic in how actors receive the characters and in how they give the performance. At the most technical level, without the actors being empathic in their expression as much as their impression, audiences could not understand what the actors are doing or talking about. At a more qualitative level, if their expressions were not sufficiently empathic, the audiences would intuit that something was off, which can come across as “fake” or “cliché.” The same is true for what we do as designers.

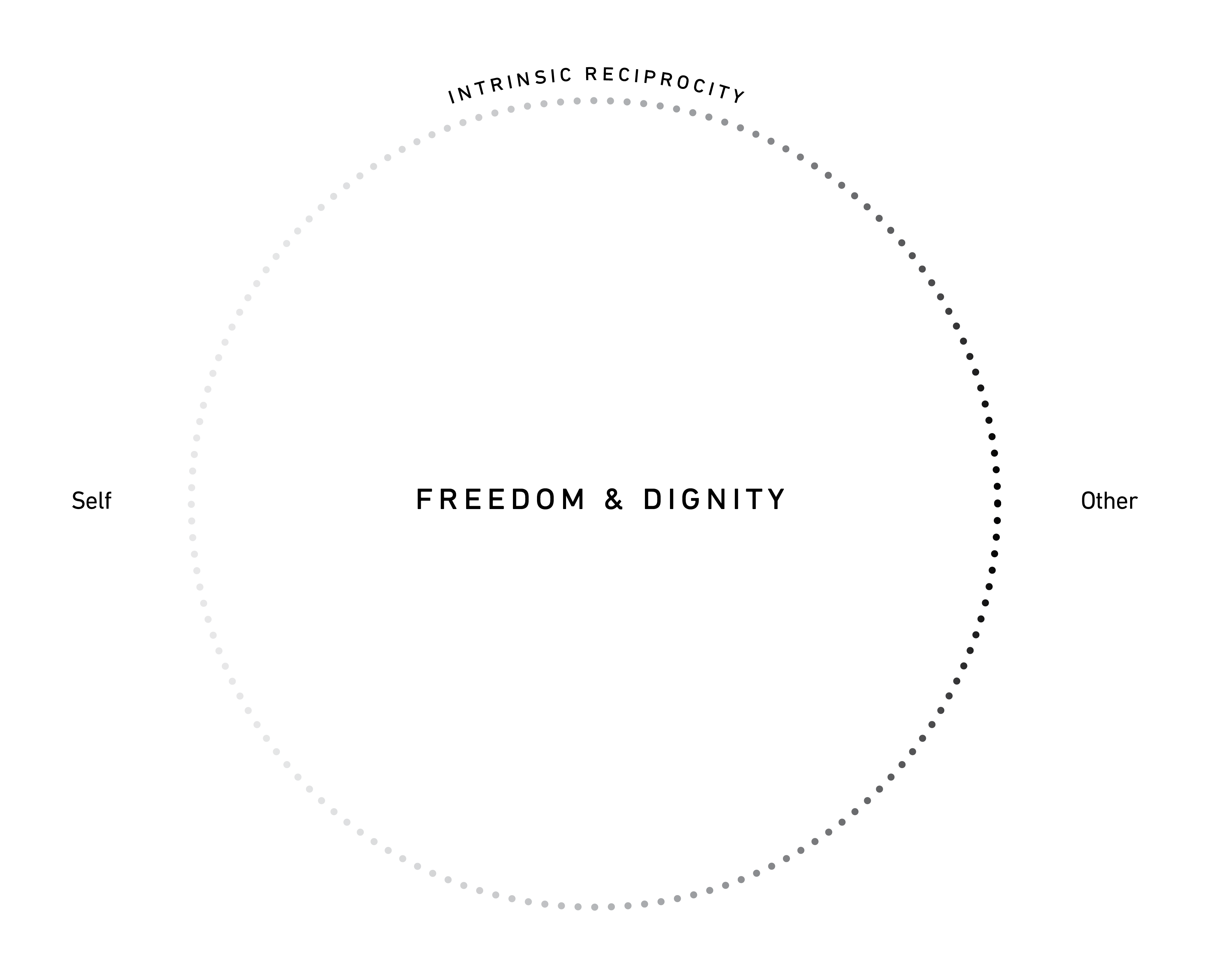

Finally, one of the most beautiful things I’ve learned while researching empathy is that as we realize empathy with “others,” we actually become better at realizing empathy with our “selves.” Have you ever had an experience where you were trying really hard to write clearly for other people, and it actually helped you better understand what you were thinking? How about the time when you tried to teach others something, and it actually helped you better learn the material yourself? Provided that it stems from a genuine and sincere motive, realizing empathy can be intrinsically reciprocal. Not reciprocal in the sense of giving and receiving gifts, but in the sense that the act of giving is in and of itself an act of receiving. This is neither selfish nor altruistic. It is simply a loop that cannot be untangled without losing its meaning.

Concepts of freedom and dignity have often been framed as centered around individuals. Through the lens of empathy both concepts take on a relational meaning that cannot be completed without a loop forming between self and other.

Image of woodworking in progress courtesy Shutterstock.

- Consumer products, Design, Design Tools and Software, Digital Publishing and eBooks, Direct Observation Research, Emotion, Empathy, Human factors, Personal and Professional Development, Product design, Product Releases and Redesigns, Project Management, Psychology and Human Behavior, Research Methods and Techniques, Research Tools and Software, Team Dynamics, Technology

Seung Chan Lim

Seung Chan (Slim) believes people who are in empathic relationships not only have lives that are more healthy & meaningful, but also more creative & effective. As an executive coach & meta-designer, he helps executives (re)design their leadership & organization: a process that challenges them to develop such relationships not only with their team & customers, but also themselves.

Slim has spent 18 years exploring the role of design & empathy in innovation. He has spoken at Harvard Business School, Cornell Johnson School of Management, McGill's Desautels Faculty of Management, Rotman School of Management, SAP TechEd, FUSE, and TEDx. He has also authored an award-winning book titled "Realizing Empathy: An Inquiry into the Meaning of Making." Slim's past clients include American Eagle, Eaton, General Electric, Merill Lynch, Siemens, and Whirlpool. Innovation efforts he's partaken have won awards such as the CES innovation award.

Slim's journey started with helping fortune 500 companies innovate. From this experience, he learned that companies struggling to innovate have to overcome their unawareness & bias toward their customers before they can innovate. The muscle required to do so? Empathy.

Slim then conducted anthropological research on how artists innovate. From this experience, he learned that visual & performing artists struggling to innovate have to overcome their unawareness & bias toward themselves, their subject matters, or their materials before they can innovate. The muscle required to do so? Empathy.

Slim now helps CEOs develop a culture of innovation. From this experience, he sees that CEOs are like artists: mired in so much uncertainty and complexity that it's no wonder they feel lonely, isolated, and anxious. So Slim helps them manage or overcome the unawareness & bias underlying such uncertainty, complexity, loneliness, isolation, and anxiety. Why? So they can more effectively lead their organization through growth & innovation. How? By helping them develop the muscle required to do so. Empathy.