Save

With our eyes on our screens more and more, what’s happening to our public spaces? Are they less congenial, less bustling, less safe? A number of recent books, such as The Circle by Dave Eggers and Ambient Commons by Malcolm McCullough, cast a critical eye at an always-online society. And, in a tragic turn, a San Francisco State University student was killed in September while leaving a crowded train; passengers, engrossed in their devices, hadn’t noticed a man on the train waving a gun around. We asked a panel of UX experts to weigh in on the ramifications of digital cocooning.

With smartphones, we walk around with the capacity to be talking, texting, or tweeting with one another all the time. Yet we’re missing out on what’s happening right in front of us. Why does social media make us, in some sense, antisocial?

Christina Wodtke: Everyone is talking about our need to be connected all the time, but no one (as far as I’ve seen) is talking about our increasing cocooning of ourselves from each other. The police procedural constantly provides us examples of bad things that can happen to us, with shows like “CSI” illustrating that apparently safe people can become our kidnappers and killers. But to be continually hyper-alert is exhausting. So instead we put up digital “do not disturb” signs so we don’t have to deal with strangers, which makes us more vulnerable to significant harm.

They also shield us from the petty guilt of not helping our fellow humans who are less fortunate, such as the homeless and old folks in need of a seat. In San Francisco, where a recent shooting occurred, one is continually asked for money. Even the kindest of us can’t give to everyone who asks, so it becomes easier to hide.

Randy Farmer: Attention is a scarce resource, and it can be dangerous to focus inwardly all the time. I first noticed this before smartphones. Airports used to be social/public spaces (and I liked to spend time interacting with people there) before cell phones and Bluetooth headsets. Now, time spent at airports is seen as “down time” that could be more efficiently used for business/personal relationships (texting), so these public, “third” places are quickly losing their efficacy as a way to interact with the greater community. And it’s only getting worse. The FAA is allowing more use of electronics on flights, and all the parks in NYC have Wi-Fi.

“Down time” used to mean a chance to relax and look around. Now it’s considered “dead time” that needs to be filled. Heads up has become heads down. Sad.

Down time used to mean a chance to relax … Now it’s considered dead time that needs to be filled

Brenda Laurel: At the memorial of the 50th anniversary of the death of Martin Luther King, we saw King’s great speech at the Lincoln Memorial over and over again. I was haunted by a picture of what that moment would have looked like today. Everybody would be taking pictures or texting with their phones. Dr. King might himself have felt isolated. To paraphrase Cassius in Julius Caesar, the fault is not with our cellphones but with ourselves. This is a failure of civility—of plain old manners—as well as a failure of mindfulness. As interaction designers (paradoxically), I think we can make some interventions in this space.

What are some design approaches that could mitigate the effects of digital cocooning?

Christina Wodtke: Design could help this problem in a myriad of ways, from having a “public place” setting that allowed only audio or only visual. When I run or bike, I only listen to porous audio like podcasts so I am alert enough to react to danger. Once we shut off our ears and eyes, we are utterly defenseless. The iPhone already has a “do not disturb” setting; maybe it’s time for a “please disturb” setting.

Design could also help in a much more significant way by reminding us of the humanity of our fellow passengers and making sure places like trains and subway read as safe so people would not feel such a strong urge to psychically hide. Ride a Skytrain in Bangkok. Bangkok has the same degree of homelessness and crime, same varied socioeconomic status of riders, yet the Skytrain feels safe and a only handful of folks hide in electronics. The trains are well designed, well maintained, and comfortable, with many signs reminding you to give seats to children, pregnant ladies, older folks, and monks. As well, there is always a TV on, and while in Bangkok it only shows commercials, I can imagine a world in which news or sports are shown as well, encouraging people to be eyes up. When places feel safe, we can relax and people-watch, and this makes those places even safer. Jane Jacobs, in her amazing treatise The Death and Life of Great American Cities, points out that what makes a place safe is “eyes on the street.” Our public transit needs eyes on each other to keep each other safe.

Randy Farmer: Though technology has been developed to prod us into changing new potentially harmful behaviors (such as smartphones auto-disabling texting while moving in a vehicle), it’s no replacement for changing our culture.

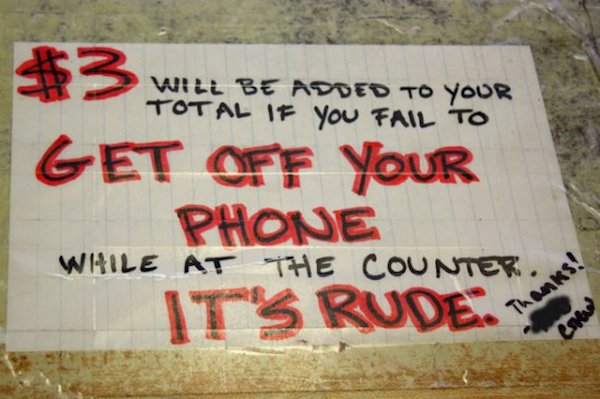

We need to consider designing our environments to remind and teach us how to interact and consciously seek “down time.” Some businesses have taken on the role of etiquette guardians:

Brenda Laurel: Both Christina and Randy make good points. I imagine “public interactives” that might allow us to see together our own public environments and gatherings in different ways. Mindfulness meditation apps already exist (for example, Smiling Mind and Take a Deep Breath). Beyond this, design applications or environment remind us to breathe and be present.

Do you engage with strangers when you’re in a “third space”—standing in line at the post office, waiting out an airplane delay? Or, in those cases, are you grateful to have an electronic device at hand?

Christina Wodtke: Most of the time, my biggest fear is being put into that situation. I’m intensely introverted. On a recent flight back from Prague, the entertainment system was not working. When the food heating system also broke, my neighbors and I started talking. We ended up connecting, but it took a shared misery. As well, it helped that I was playing a game on my iPad. The iPad is a big surface, easy to peek at, and games are inherently social. If I had been watching a movie, especially if I’d had headphones on, my seatmate wouldn’t have used the game as a social object to start a conversation. He was really interested in watching me play Frontier Rush, asked about how to play, and started to suggest moves I should make. (He was a man in his ’70s whose wife was trying to talk him into an iPad. I made the sale that night.) I wonder if the post office or the airlines could create similar play spaces where it would feel safe to connect.

Randy Farmer: Recently I was in a fast-food restaurant and an older woman came in, looking lost and asking for driving directions. The twenty-year-old at the register was at a loss for helping her, even though I am certain he was carrying a smartphone. I was waiting for my order, so he asked me to help her. I quickly loaded my maps app and told her the step-by-step directions (which she wrote with pencil on her physical map). The cashier was grateful and a bit embarrassed that he didn’t know the directions (how would he, growing up without paper maps?) and that he didn’t even know how to handle the social encounter well enough to figure out that he had the solution in his pocket.

Our tools are teaching us a new kind of social helplessness, and also providing us an easy means for escape when we can’t cope with the fact we’re directly interacting less and less. This is a vicious spiral.

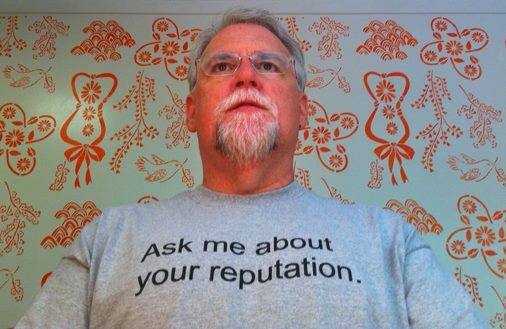

Social rules design has helped in the past and can help us today. Our technologies can, and must, take a role in this, but we must start with the goal in mind. We’ve started using tech for physical exercise, something that was also declining, and we can do the same for social health. One might imagine a Fitbit for socialization. Or you could just get a t-shirt:

Brenda Laurel: Randy, I want one of those. I do see many folks staring at their phones when waiting in line and the like. I love observing and talking to people in those situations, so I rarely bury my head. On the other hand, if the wait is two hours or something, I’ll certainly end up grabbing my iPhone. I agree with Randy that this is really about socialization. I don’t think we can design social “rules” (although we might model more civil and sociable societies in things like multiplayer games).

One of the best social times I’ve had lately was at the LGBT luncheon at the Grace Hopper Conference. It seemed like the usual conference lunch scene—sitting next to people you didn’t know, some of whom knew one another. But the “emcee” suggested topics for discussion and eventually we got into making comments to one another publicly on a variety of subjects. I felt the community draw closer, and I had special buddies throughout the conference because of that experience. At Grace Hopper I also learned about “lean in” circles as a way to enhance our engagement in discourse as well as community.

Like what our experts had to say? You can have them bring their brains to you. Randy Farmer, Brenda Laurel, and Christina Wodtke are available for consulting and training through Rosenfeld Media.

Image of silkworm cocoon courtesy Shutterstock.

Mary Jean Babic

Mary Jean really enjoys drawing on her journalism and writing background to help tell the Rosenfeld Media story. After graduating from Northwestern University, she was a daily newspaper reporter in Michigan for six years. After that, she embarked on a life of fiction and freelance writing, earning master's degrees from Johns Hopkins University and Warren Wilson College. She's a frequent contributor to university publications, counting Michigan, Columbia, and Cornell among her clients. Her short fiction has appeared in the literary journals The Missouri Review and The Iowa Review.