Save

With Star Trek Into Darkness opening in theaters this weekend, it seems like a perfect time to survey some of the technological foreshadowing the franchise has bestowed upon us over the years.

There are few better sources for that kind of info than Make It So (Rosenfeld), a book by Nathan Shedroff and Christopher Noessel that describes in great detail the interaction design lessons we can take from science fiction.

From brain copying in Metropolis (1927) to voluminous projections in Iron Man 2 (2010), the book provides a wide and detailed account of how the tech in SF inspires the glowing things in our pockets today and the glowing things we’ll have embedded under our scalps in a few decades.

Here are some excerpts from the book that show how Star Trek staked its claim in our design imagination. We’ve selected examples primarily from the original television series and J.J. Abram’s 2009 reboot, but fans of Deep Space Nine, The Next Generation, Voyager, and the original movies will find plenty of nourishment throughout Make It So.

Enter the discount code UXMAGMAKEITSO and get 20% off when you buy the book online.

Star Trek Sets the Tone for Mobile

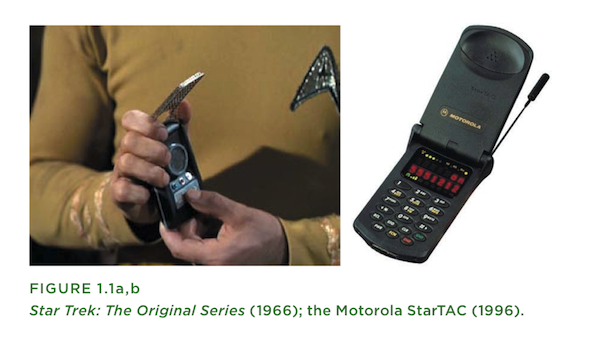

Whether we like it or not, the fictional technology seen in sci-fi sets audience expectations for what exciting things are coming next. A primary example is the Star Trek communicator, which set expectations about mobile telephony in the late 1960s, when the audience’s paradigm was still a combination of walkie-talkie and the Princess phone tethered to a wall by its cord. Though its use is a little more walkie-talkie than telephone, it set the tone for futuristic mobile communications for viewers of prime-time television.

Exactly 30 years later, Motorola released the first phone that consumers could flip open in the same way the Enterprise’s officers did. The connection was made even more apparent by the product’s name: the StarTAC. The phone was a commercial success, arguably aided by the fact that audiences had been seeing it promoted in the form of Star Trek episodes and had been pretrained in its use for three decades. In effect, the market had been presold by sci-fi.

Star Trek Presents Complex VUIs with Thinking Computers

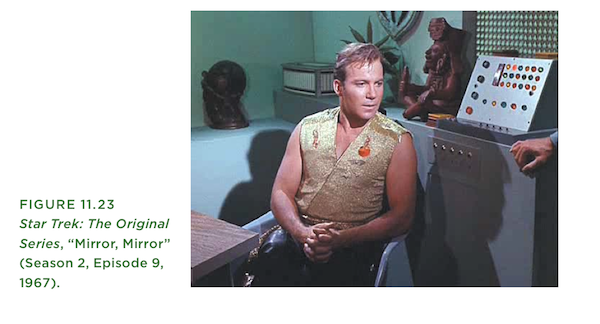

In the “Mirror, Mirror” episode of the original Star Trek TV series, Captain Kirk consults the computer to learn whether a poorly understood accident could have been produced deliberately:

KIRK: Computer.COMPUTER: Ready.KIRK: This is the Captain. Record: Security research, classified under my voiceprint or Mr. Scott’s.COMPUTER: Recording.KIRK: Produce all data relevant to the recent ion storm, correlate following hypothesis. Could a storm of such magnitude cause a power surge in the transporter circuits, creating a momentary inter-dimensional contact to a parallel universe?COMPUTER: Affirmative.KIRK: At such a moment, could persons in each universe in the act of beaming transpose with their counterparts in the other universe?COMPUTER: Affirmative.KIRK: Could conditions necessary to such an event be created artificially, using the ship’s power?COMPUTER: Affirmative.

What’s notable is that during the interchange, Kirk isn’t playing with ideas, he’s just asking yes or no questions. Even though he’s asking about something fairly mind-blowing (which could have changed the nature of the Star Trek franchise into something much more like Quantum Leap), he is essentially using the device as a reference. Still, the scene gives the sense that this is something that has never been done before, with the computer instantly modeling options and testing variables to produce its answers. This makes it a good tool for thinking.

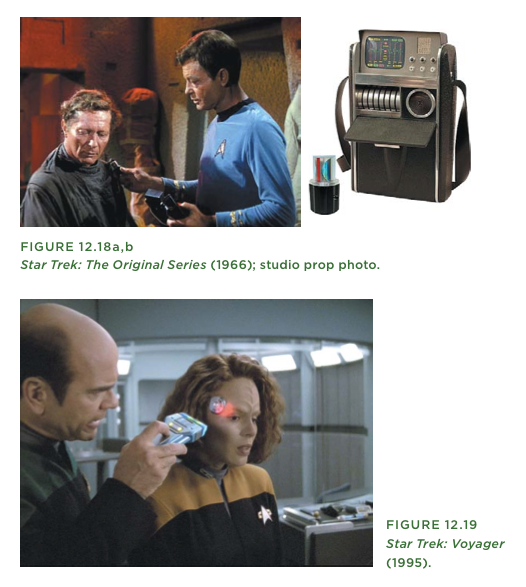

Star Trek Challenges the Future of Medical Diagnosis

The original Star Trek TV series introduced portable and fast diagnosis with its medical tricorder. The ship’s doctor, Leonard “Bones” McCoy, would wave the handheld scanner over a patient and simultaneously look at the handheld screen. Though the series never showed exactly what he was looking at, after a glance at the screen he would describe exactly what was wrong with the patient, even if the problem was obscure or the patient was an alien species. Though McCoy might have been viewing a screen very similar to the sickbay monitoring screens discussed, it is more likely that the device was also able to suggest a diagnosis based on its readings. Other series in the Star Trek franchise evolved the appearance and shrunk the size of the medical tricorder.

Few other sci-fi properties have presumed such portability and speed of medical diagnostic tools. Although the medical tricorder was largely a narrative tool rather than a serious speculative technology for assistive diagnosis, the notion of a portable and near-instantaneous diagnostic tool inspires medical technology inventors to this day. And that’s not by accident. In one deliberate attempt to have sci-fi influence the real world, Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry reportedly signed a contract with Desilu/Paramount stipulating that anyone who can create a device that operates like a medical tricorder can use the already-popularized name for their device. In essence, he is offering nearly 50 years of in-show marketing to anyone who can live up to the vision.

Star Trek Posits an Intense Vulcan Testing Interface

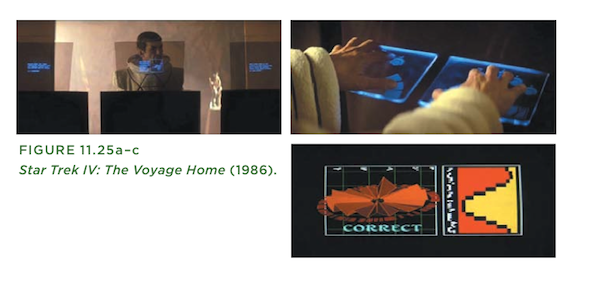

Testing is seen in the survey a few times, all within the Star Trek films. In Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, we see such a system when the recently reanimated Spock is rebuilding his sense of self and knowledge of the world.

In the testing cell, he approaches a bank of three transparent screens. When he says, “Computer, resume testing,” a metallic voice begins to ask him questions on a wide variety of esoteric topics, such as, “Who said ‘Logic is the cement of our civilization with which we descend from chaos using reason as our guide?’”3 and issuing challenges such as “Adjust the sine wave of this magnetic envelope so that anti-neutrons can pass through it but anti-gravitons cannot.” When Spock correctly answers a question, the computer responds with “Correct!” and moves on.

For each question, either the text or an illustration of the posed problem is presented on the screen and remains there until Spock answers it. He answers some of the questions vocally. For others, he places his hands on a set of touch pads. Only his gaze identifies which of the three simultaneous questions he is answering. He answers with increasing rapidity until he comes to a particularly difficult question he does not understand.

Seriously, he’s stumped.

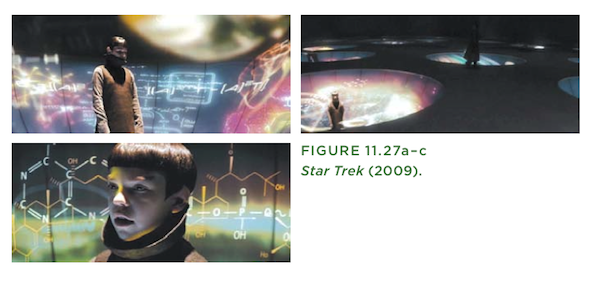

One of the most memorable examples of testing interfaces is in the Star Trek reboot film when a young Spock is attending school on Vulcan. He is standing at the base of a concave hemisphere that surrounds him with a projected expanse of overlapping and moving images, formulae, and illustrations. He responds to a voice asking him factual questions, such as “What is the formula for the volume of a sphere?” As he answers questions correctly, the related figure fades from view and another is asked. We do not see Spock make an error, so we don’t know what would happen in that case.

When the camera pulls back to reveal many similar learning pods with one student at the center of each, we understand that testing on Vulcan is done alone, and we assume that each student progresses through this gauntlet at his or her own pace.

In both cases, the interface fires a barrage of questions at the student, testing recall of facts in rapid succession.

Both of these systems equate intelligence with the simple recall of facts. Memorization is a core skill, but data in the age of the Internet is cheap. Just as or more useful is the ability to apply that knowledge—to take a complicated problem in the real world, identify what information is and isn’t pertinent, and form and execute a plan for solving it. Granting the benefit of the doubt, perhaps these testing interfaces we see are just one part of Spock’s education and there are other systems for learning other skills. It makes sense that a filmmaker would want to pick the most cinemagenic of possible learning components. This testing pod qualifies for its pace, exciting visuals, and an emotional callback to what it felt like for the audience to take difficult tests in their youth.

Star Trek Glows and So Should You

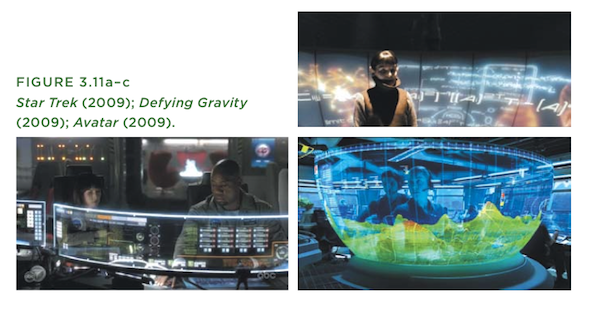

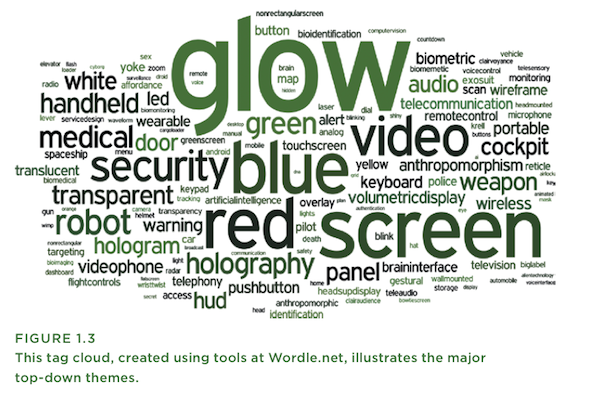

The most prominent visual aspect of speculative technology is that it glows. From lightsabers to blasters, holograms, to teleporters, most sci-fi technology emits light. It is the most common tag in our tag cloud … and any casual overview of the survey shows its ubiquity.

This effect includes on-screen elements as well. Type and other graphic elements, like lines in a map or diagram, are often a bright color on a dark background. Frequently a blur around these elements is added to enhance the glow effect. To push the technological aspects of the interface, diagrams and images are often rendered as wireframes instead of solid or patterned fills, creating more opportunities for high-contrast glowing.

Why does sci-fi glow? We suspect it’s because things of power in the natural world glow: lightning, the sun, and fire. Other heavenly bodies glow as well—stars, planets, and the moon (especially against a black background)—and have been long associated with the otherworldly. Additionally, living things that glow captivate us: fireflies, glowworms, mushrooms, and fish in the deep seas. It’s worth noting that while most of real-world technology glows, a lot of it doesn’t, so its ubiquity in sci-fi tells us that audiences and sci-fi makers consider it a crucial visual aspect.

Regardless of the reasons, designers should be aware of this principle. If you want your interface or new technology to seem futuristic, it’s got to glow.

- 3D Graphics and Interfaces, Artificial Intelligence, Augmented Reality, Data visualization, Design, Digital Publishing and eBooks, Entertainment and Humor, Healthcare, Information Design and Architecture, Interaction Design, Interface and Navigation Design, Mobile Technology, New and Emerging Technologies, Product design, Technology, Visual Design

Christopher Noessel

This user does not have bio yet.

Nathan Shedroff

This user does not have bio yet.

UX Magazine Staff

UX Magazine was created to be a central, one-stop resource for everything related to user experience. Our primary goal is to provide a steady stream of current, informative, and credible information about UX and related fields to enhance the professional and creative lives of UX practitioners and those exploring the field. Our content is driven and created by an impressive roster of experienced professionals who work in all areas of UX and cover the field from diverse angles and perspectives.