Save

UX as a design and research paradigm is subject to numerous understandings, definitions, and applications. This multiplicity in approaches and interpretations of the term has been more or less accepted, yet the essence of experience, the experiential component of UX is psychology.

Experience can be defined as thought and the ways that people mentally represent and make sense of phenomena. Often, the focus in UX research is conscious experience—technological encounters and interactions that we actively recall from the past, which subsequently inform and influence our interactions in the present and future. By explicitly including experience as a design goal in human-technology interaction, we have opened Pandora’s Box.

No longer are designers, engineers, and, more critically, corporations simply interested in knowing what works and what doesn’t. Rather, we have unleashed the greater philosophical mysteries of the mind into the realm of design practice. Some attempts to explain the unexplainable can be seen in the work of René Decartes and Charles Sanders Peirce. In particular, this article uses Charles Sanders Peirce’s theories of logic to demonstrate how experience operates through sign systems and interpretation.

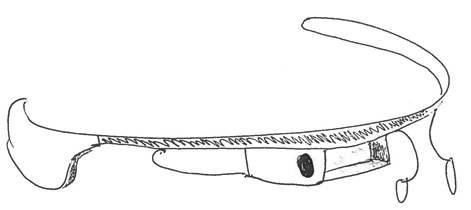

In this article, experience is described as interpretation, and semiotics are applied to analyze the new wearable augmented reality product, Google Glass. Various readings of Google Glass are offered, and a prediction is generated which implies that through drawing on the traditional syntax of spectacles (eye glasses) a greater user group will be reached including not just technology leaders or adventurers, but also technology laggards.

[google_ad:WITHINARTICLE_1_234X60_ALL]

Experience takes place before, during, and after technology usage, and by making new devices more familiar to the target market, there is increased likelihood that user experience will be positive.

Age-Old Experience

For centuries philosophers have been trying to explain conscious experience and the workings of the mind. Most notably, mathematician René Descartes drew attention to the constructed nature of thought. While Descartes is notorious for being one of the forefathers of mind-body dualism (Rozemond 2002), what is often forgotten are his insights into the subjective nature of experience. That firstly, we all think and experience independently, and secondly, that what is perceived and consequently experienced is the result of the way our minds process information (Descartes 2008).

UX is the communication of minds through the language or sign systems of design

Experience is generated through perception (information gathering), selection, composition, and editing that occurs in the mind. To emphasise this characteristic Descartes contrasted the physical (the body and real world elements) with the metaphysical (the mind and thought).

Peircing the Mind

In a somewhat similar vein, another mathematician, Charles Sanders Peirce, also sought to explain the workings of the mind and of logic. Peirce rejected the greatly positivist views of his time (b. 1839), particularly regarding psychology, and argued that thought, logic, and experience in general were the products of connectivity. Experiences, he surmised, are constructed by continuous connectivity to previous experiences and memories, and the overlaying of these with particular feelings: emotions (Peirce 2009).

Peirce took care in distinguishing his theories from Descartes’ by introducing a third element: betweenness. What Peirce suggested was a phenomenological link between the physical and metaphysical, or physical and psychical worlds, which is where his theorisation of sign systems began.

Peirce’s theory of logic states that there is always some connection between thought and the real world. His simple sign theory presents the sign or symbol (signifying element), the object (that to which the signifying element refers), and the interpretant (thought, mental representation, or the interpretation of the sign). This simple model of the sign system can be exemplified on a basic level in terms of the phrase “Google Glass,” which is a textual symbol comprising a relation to the object through arbitrary agreement.

[google_ad:WITHINARTICLE_1_468X60]

Through the Looking Glass

Google, has developed a product for everyday, personal augmented reality (AR) experience, and has endowed it with the name “Google”—the company name—“Glass,” a name which refers to a previously agreed upon English term describing both glass as a substance, and glass as an object.

Subsequently, the actual object being referred to is a pair of what appear to be glasses minus the lenses. Instead of the lenses, the frames feature a small rectangular glass and miniscule computer in the top right-hand corner of the frame. The interpretant, or interpretation of the phrase “Google Glass” can be anything: this is both Descartes’ and Peirce’s point.

While Descartes argues that the thought or interpretation can be literally anything as we have no way of knowing the real relationship between the physical and metaphysical, Peirce argues that the metaphysical is influenced by the physical, and namely past experience. In other words, in light of Peirce’s insight into continuous affectibility, memories of past phenomena and encounters always influence what is encountered now and in the future.

So, when encountering the phrase “Google Glass”, someone who is familiar with the product may, for example, envision (or mentally construct) the augmented reality tool housed in a pair of lense-less glasses.

Mental representation of Google Glass by someone familiar with the product

Someone who is not familiar with the exact product but is familiar with the company may mentally represent the Google logo and then either: a) add “es” to the word glasses, constructing the representation of an actual pair of glasses; or b) imagine the logo and a version of a glass. Our interpretations are based on mental information content that we already possess.

Hypothetical mental representation of someone familiar with Google and “glass” but not with the exact product

On a more abstract yet ever-present level, the object is not simply a material product. Instead, the object becomes the actions, functions, operations, and values that are referred to by both the name and the product itself. Thus, the product—the pair of lense-less glasses with a data camera and AR glass screen—also refers to other objects such as information, connectivity, documentation, communication etc. This, in turn, alludes to societal values, ubiquity, mobility, compactness, efficiency, and, again, information. Based on the user’s position (societal, cultural, historical etc.), personality, and prior experiences, the interpretant may comprise reference to any number of these “object factors,” in addition to being attributed new meaningful components and emotional associations.

The Process of UX

Along these lines, UX can be understood as a semiotic process. In other words, UX is the communication of minds through the language or sign systems of design (Pinker 2005). Yet, as many communication theorists will mention (Ogden and Richards 1923; Krippendorff and Butter 1984) the process of communication is always arbitrary in nature. For instance, before encountering Google Glass live, users from a lower socio-economic background may associate the gadget with unattainability due to its cost. Likewise, in terms of accessibility the design may generate a two-fold effect among users traditionally considered late adopters or laggards.

The very nature of the device as a cutting edge tool for everyday AR experience may alienate users who perceive the highly personal and predictive nature of the design as being invasive and complicated. Yet, the employment of the widely recognizable and traditionally inspired form found in the glasses frames themselves—coupled with the name Google Glass—may encourage traditional laggards to embrace the technology. Thus, the device may symbolize a new extension to traditional technology.

How to View UX

When viewing UX as a sign, designers can make concrete decisions about who they are going to appeal to, how they are going to appeal to that audience, and what stylistic language to draw upon in order to attract particular target users.

Google Glass is used here as an example of high-tech and complex technology, which I predict will succeed on the mass market among all types of users from technology leaders to laggards, simply because of the use of traditional syntax, making a direct reference to users’ past (low-tech) experiences and apparent analogue simplicity.

Image of man in glasses courtest Shutterstock.

Rebekah Rousi is a researcher of user psychology and PhD candidate of Cognitive Science at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland. With a background in visual arts and cultural studies, Rousi has brought a Humanities perspective to several projects of human-systems interaction and user psychology, these include: the ITEA2 Easy Interactions project, Theseus and Theseus II. In nature, Rousi's work synthesises problems, challenges and innovations with scientific investigations, aiming at devising consistent methods for measuring factors such as user experience. In 2010, Rousi undertook a 3 month researcher exchange at the University of Adelaide, Australia. Rousi is particularly interested in the psychology of user experience, affective human-technology interactions and the mental factors of design encounters.