Save

In John Maeda’s recent article, “The Distinction Between Designing for Enterprise vs Consumer Customers,” he explains why designing for enterprise is different, and perhaps more challenging, than designing consumer applications.

However, as a person who has designed applications for enterprise companies as well as small business and consumer products, I’ve come to believe that the distinction between designing for consumer and enterprise applications has rapidly narrowed over the last several years.

For an enterprise product to achieve the greatest user adoption and long-term success, we should deliver an experience for end-users that meets the same usability, performance, and brand standards evident in consumer products.

The user has become the decision-maker.

For traditional enterprise products, the model used to be that you sell to a C-level executive at the company, and the employees then use the tools they are provided. If an application was painful to use, employees would use it as little as possible, and instead use time-consuming, often manual, work-arounds to avoid spending time in the tool.

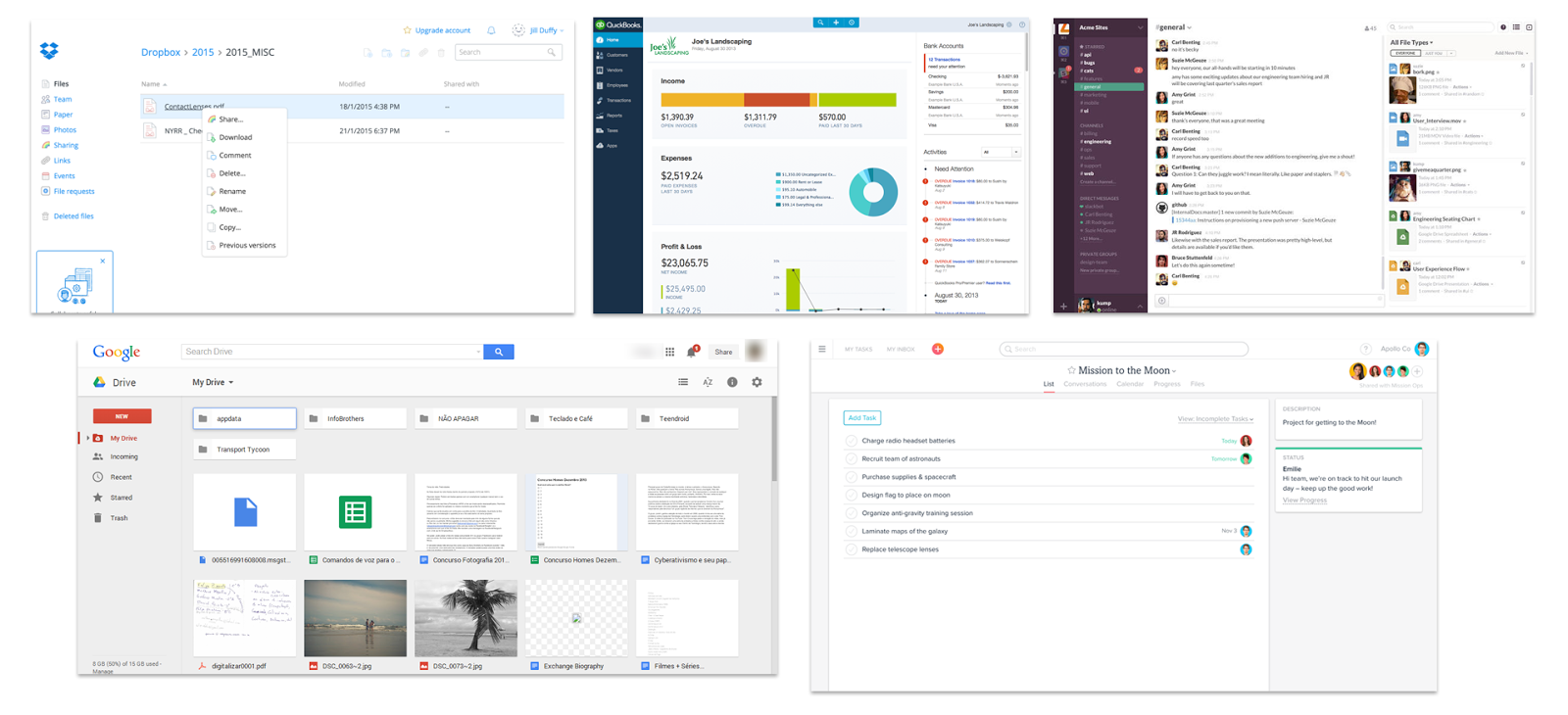

Today, teams and employees often choose their own products. That means it’s the best product and design that wins, rather than the best sales and marketing. Slack, Sketch, Dropbox, Sunrise, Google Drive, and Asana are all examples of this trend.

Some of the new generation of enterprise apps: Dropbox, Intuit, Slack, Google apps and Asana

Because switching between platforms costs so much less than it used to, it’s a lot easier to choose your own tools at work. I see employees choosing the calendar tool that works for them, the communication tools, the document storage system, even design tools like Sketch. More and more, large team tool decisions are made bottom up. Users are picking the software they love, rather than the software that was forced on them.

What this means is that companies building enterprise products need to be thinking less and less about wining and dining CIOs, and more and more about how to apply consumer thinking to enterprise product design.

Don’t rely on a sales team for user growth.

Your goal as a designer is to build an app so great that your users want to shout about it from the rooftops, and share it with all their teammates.

Adoption, in this scenario, is organic, and users will ultimately be more loyal to your product than something they’ve been “forced” to use.

Performance matters.

Though many enterprise applications are cloud-based (e.g. Salesforce, Quickbooks, Marketo, Infor, etc), consumer expectations around speed are no different than they are for desktop apps.

If a cloud-based application takes time to load, users will leave. Gmail and other online applications have already set the standard for responsiveness and performance.

Create a first use experience that allows users to succeed on their own.

As explained in the free guide The Future of Enterprise UX that I wrote with the collaborative design app UXPin, designers should also strive to create an application onboarding experience that doesn’t require outside training.

The user has become the decision-maker

This is still an area where I see hesitation at companies designing enterprise products. People will say, “Well, a little bit of training is required for people understand this tool, because it’s a little more complicated than consumer applications.”

Building products for people to use at work shouldn’t be an excuse for bad design. If you follow common UI constructs–orient users, give them a concrete user benefit, and leave them feeling that they have gotten something valuable for their time–they will continue to learn to use your product just as they learn video games, mobile apps, and everything else.

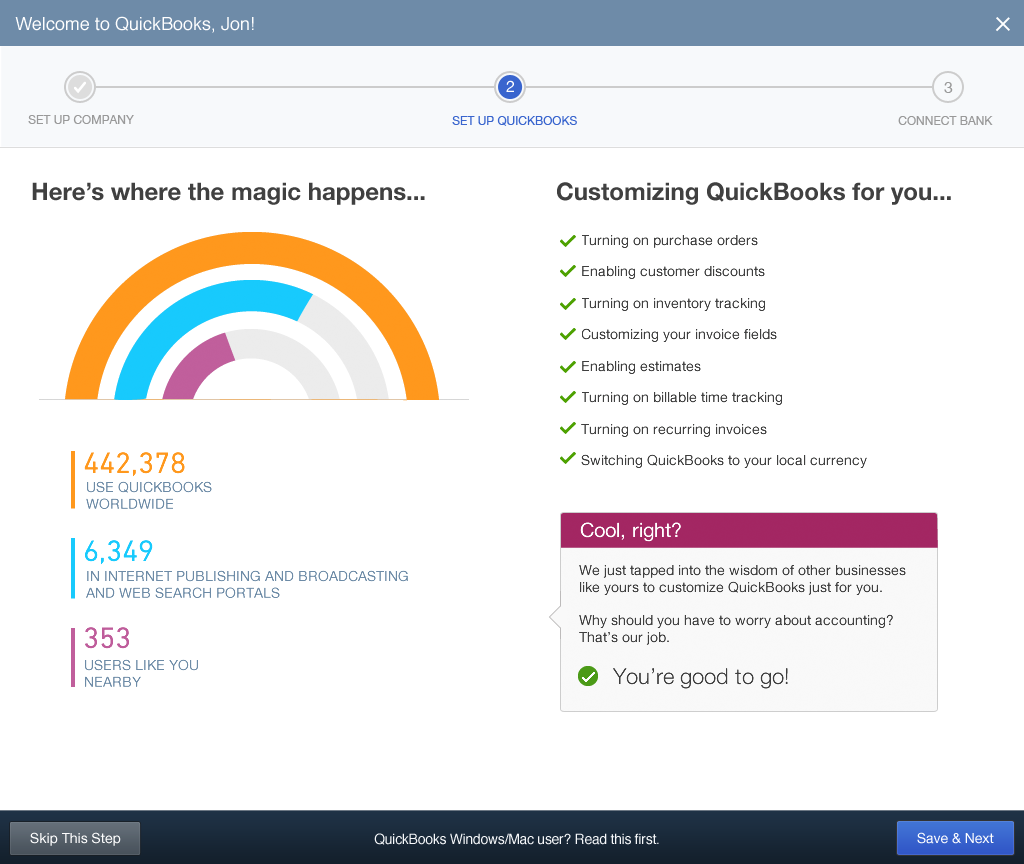

For example, when designing the onboarding experience for Intuit’s flagship product QuickBooks, we asked for key information about the business, then customized the experience based on the information given, doing some of the initial setup work for the user. This helped the product feel like it was designed just for the end-user and their business.

We created a screen with a graph showing the number of Quickbooks users in the same industry and location. Doing this wasn’t required in a traditional onboarding experience, but conversion was higher for this flow than it was for onboarding experiences with fewer steps. The screen told people, “We will save you time by setting up the product for you,” and it also reinforced that they were choosing the industry leader.

Quickbooks first use experience

The new bar for a first use experience is not just whether it works for the person trying to use it. It has to be good enough for them to feel comfortable advocating for the product with the rest of their team and their company.

Make your product customizable by the user and team.

Enterprise customers shouldn’t accept the notion that they need implementation specialists to tailor the product for the customer; customers should be able to do that themselves.

If you design an enterprise application such that it can be customized by the teams using it, you give them a sense of investment and ownership in the product. You empower them and give the users confidence. The users make the product right for them, and therefore become much more loyal.

What’s more, as an enterprise vendor, if you spend your time/resources on custom implementations for your customers, you won’t have enough resources to invest in applying customer feedback and innovating.

The risks and opportunities in designing for enterprise

Though the gap between enterprise and consumer user experiences is narrowing, there are a few lasting differences that are important to consider in designing business applications.

It can be riskier to be innovative.

With enterprise tools, you are working with data that is extremely valuable, so it can be frustrating for users if you bury that data in playful and unusual interactions. As a designer, you want to adhere to user interface standards that already exist, focusing your innovation on the parts of your product that are better than what’s already out there.

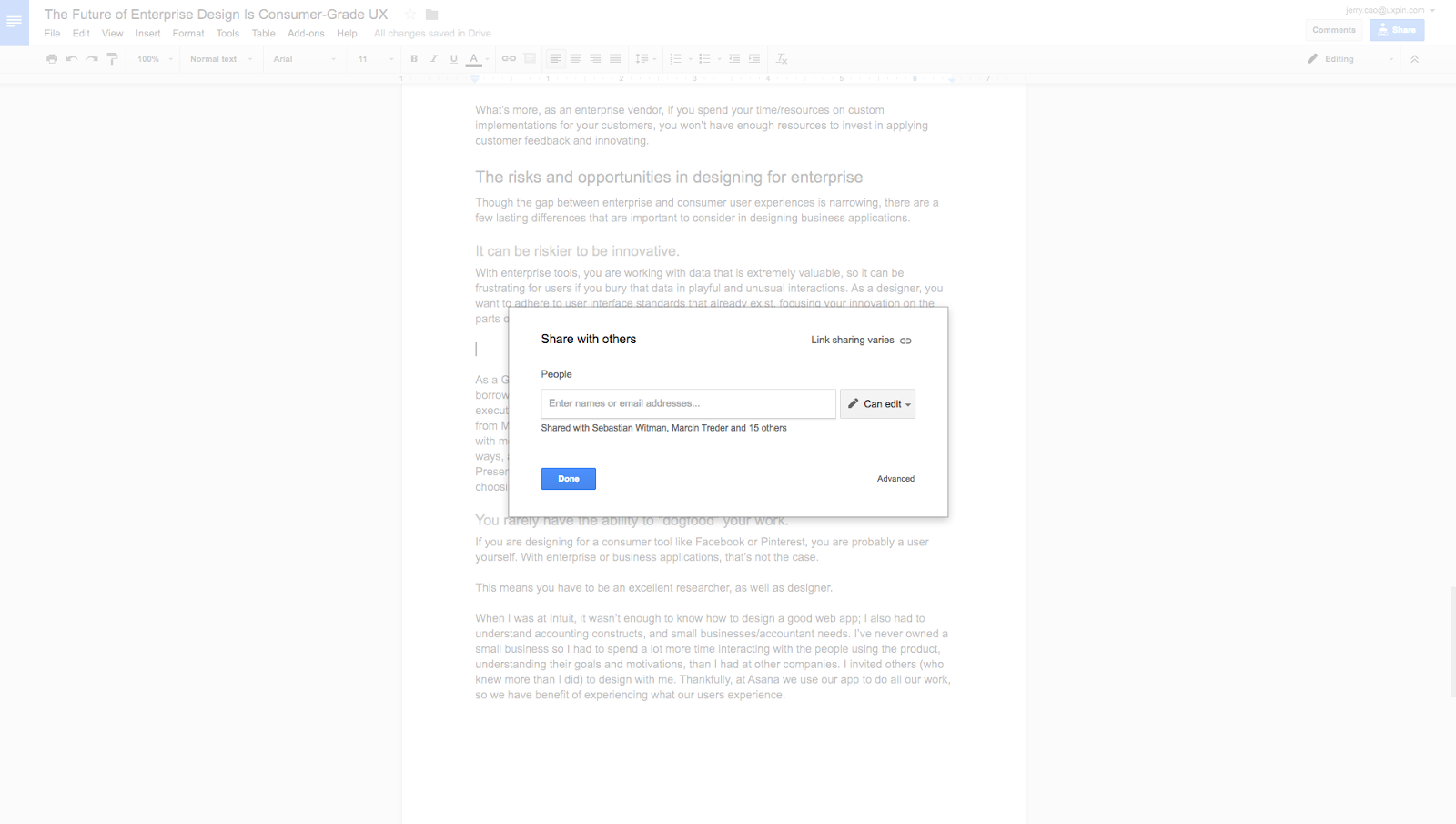

Sharing in Google Docs

As a Google Docs user, I don’t have to figure out how to use the document editor, because it borrows so heavily from what I already know from using Microsoft Word. What Google nailed in execution was focusing innovation on the differentiator: the collaboration tools that set it apart from MS Word today. The only thing I need to learn in the app is how to invite someone to edit with me. Once I have that concept down, I can use the application in thousands of interesting ways, and build on what I’ve learned as I use expand my use to other related products, like Presentations. (I’ll be the first to admit that it can be hard for a designer to be disciplined in choosing where to use existing paradigms, and still be very focused on where to reinvent).

You rarely have the ability to “dogfood” your work.

If you are designing for a consumer tool like Facebook or Pinterest, you are probably a user yourself. With enterprise or business applications, that’s often not the case.

This means you have to be an excellent researcher, as well as designer.

When I was at Intuit, it wasn’t enough to know how to design a good web app; I also had to understand accounting constructs, and small businesses/accountant needs. I’ve never owned a small business, so I had to spend a lot more time interacting with the people using the product, learning and understanding their goals and motivations, than I had at other companies. I invited others (who knew more than I did) to design with me. Thankfully, at Asana, we use our app to do all our work, so we have benefit of experiencing what our users experience.

Conclusion

I’m excited to see more interest from designers and design leaders in creating enterprise tools, and I think it’s because the gap between consumer and enterprise is narrowing.

With consumer apps, you can feel good about designing a tool that impacts billions of users, and you can bring entertainment to the world. But there is a challenge that leaves the designer feeling conflicted over time. Many consumer apps monetize with ads, so the user goals and the company goals are not in sync. The user is thinking “I’d like to watch this video, and the company is thinking, ‘How can we get the user to view more ads before they watch this video.”

The beauty of designing for enterprise and other paid applications is that the end-user’s goals and your business’ goals are aligned. Your company benefits only when the user is successful at using the app. With enterprise tools, you are building products that help organizations and their employees meet their goals, helping all businesses do their work better.

For more practical enterprise UX best practices, check out the free guide The Future of Enterprise UX by the author. The guide condenses her nearly 20 years of enterprise design experience into 47 pages of example-based advice. Case studies included from Asana and Intuit.

Amanda Linden

Amanda Linden is Head of Design at Asana. Prior to Asana, she was the Design Director for Intuit’s small business division. There, she led the redesign of Intuit Quickbooks, and also managed their payroll and payments experiences. She has also written the free e-book The Future of Enterprise UX with the collaborative design app UXPin.