“The power of authoritative knowledge is not that it is correct but that it counts.”–Brigitte Jordan

They stride into the arena wearing the maize and blue. They are tall, strong, fast, and confident they will conquer the world. It wasn’t easy getting here, but after countless hours of practice, weight training, and gut-busting cardio workouts, they have arrived. The price is high. It costs thousands of dollars a year to play at this level, but without access to the best coaches, facilities, and technologies, you might as well just go home.

It’s six-thirty in the morning in January, and as I watch our fourteen year old daughter’s volleyball team make their way to the court, my feelings are mixed. I’m not happy about waking up at five o’clock on a Saturday to drive for an hour through the snow. A few years ago, I’d have laughed at this elite sports scene. Now I’m a part of it. Claire is staying fit, making friends, building self-confidence, learning teamwork.

Still, it’s over the top. Our club makes me uneasy. What bothers me most is the uniforms. They are beautiful. Since our club is run by the University of Michigan, our girls are decked out in blue and gold. While a lot of teams satisfice with cotton t-shirts, we have personalized, lightweight, wicking Nike jerseys with matching shorts, warm ups, and backpacks. As our girls prepare to play, I can’t help feeling we’re on the wrong side of the tracks. And sure enough, we are crushed by the t-shirt team, just like in the movies. Later, after a day of losses, I tell Claire not to worry, it’s the first tournament of a six-month season, the team will get better.

Of course, it was all downhill from there. Our coach was a hard-ass all season. One girl was berated for not hitting hard enough. Later it turned out her finger was broken. Claire was told she couldn’t take a break even though she felt sick. Soon after she was vomiting into a bucket. The girls were taught how to trick the referee. They were instructed to lie. The coach invited them to voice complaints. Claire did so and found herself benched. The parents weren’t any better. Our alpha mom reduced other moms to tears, taunted the opposing teams, and paid for weekly private lessons with the coach. This looked like pay-to-play corruption to us, but several of the parents said that’s simply how you play the game.

The next year we switched clubs. The new one was a little less expensive and a whole lot better. When the coach told the girls it was okay to miss practice for homework, since education is more important than volleyball, he actually meant it. When we lose a game, you won’t hear a word from our alpha mom. We don’t have one. The girls practice in an old warehouse, no windows, flickering lights. It’s nothing fancy. Neither are the uniforms. And that’s the way we like it. We found our fit.

Cultural Fit

In the 1990s, as co-owner and CEO of a consulting practice, I hired and managed several dozen employees. Mostly we got it right, but once in a while we hired someone who didn’t fit. The consequence of a cultural mismatch is often compared to an immune system response. It’s not a bad analogy. The first symptom is inflammation. This pain is followed by isolation of the foreign body. But in organizations, there’s no need to destroy the antigen. Few people endure outsider status for long. They quit. At the time I thought there was something wrong with those people. My enculturation was complete. Now I know it simply wasn’t a good fit.

As a consultant for two decades, I’ve been a tourist in all sorts of cultures. I’ve worked with startups, Fortune 500 companies, nonprofits, Ivy League colleges, and Federal Government agencies in multiple countries. My clients have included folks from marketing, support, human resources, engineering, and design. Being exposed to diverse ways of knowing and doing is one of the best parts of my work. But my interest runs deeper than cultural tourism. Over the years, I’ve realized that understanding culture is central to what I do.

First, as an information architect, I must understand the culture of users. When I run a “usability test,” evaluating the system is only half my aim. I also hope to uncover the beliefs, values, and behaviors of the people who use the system. Before imposing my own theories, I want to see how they define their world. What can we learn from their use of language and the way they sort concepts into categories? Which sources of information and authority do they trust? What is the meaning behind their behavior? For years, I’ve used lightweight forms of design ethnography as part of my user research practice. It’s helped me to better understand and design for oncologists, middle school children, university faculty, bargain hunters, and network engineers. And, as the systems we design only grow more rooted in culture, I’m convinced we must dig deeper into ethnography.

Second, as an outside consultant, I must understand the culture of the organizations for which I work. Today’s systems aren’t only integral to the lives of users, but they are progressively part of the way we do business. To improve user experience, it may be necessary to change the org chart, metrics, incentives, processes, rules, and relationships. Connections and consequences run all the way from code to culture. Software that doesn’t work “the way we work” will fail like an employee who doesn’t fit. So we must also study and design for stakeholders. In my research, I always interview a mix of executives and employees about roles, responsibilities, vision, and goals. And I’ve learned that if I don’t ask the right questions in the right way, or if I don’t listen carefully and read between the lines, I may mistake the surface for substance and invent a design that won’t fit.

Figure 4-1. We must design for a bi-cultural fit.

In short, the right design is one that fits the company and its customers. A mismatch on either side results in fatal error. We must use ethnography with our users and stakeholders to search for a bi-cultural fit. This is tricky since culture is mostly invisible. That’s why we should start with a map.

The right design fits the company and its customers—a mismatch on either side results in fatal error

Mapping Culture

Edgar Schein, professor emeritus at MIT and the father of the study of corporate culture, offers a useful definition.

Culture is a pattern of shared tacit assumptions that was learned by a group as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, that has worked well enough to be considered valid and to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems.

Culture is a powerful, often unconscious set of forces that shape both our individual and collective behavior. In an organization, culture is reflected in “the way we do things here.” It influences goals, governance, strategy, planning, hiring, metrics, management, status, and rewards.

And culture is an artifact of history. Organizational culture is rooted in the values of the entrepreneur. In the early days, as leaders struggle to build the business, the beliefs and behaviors that lead to success are internalized. Eventually they become taken for granted, invisible, and non-negotiable.

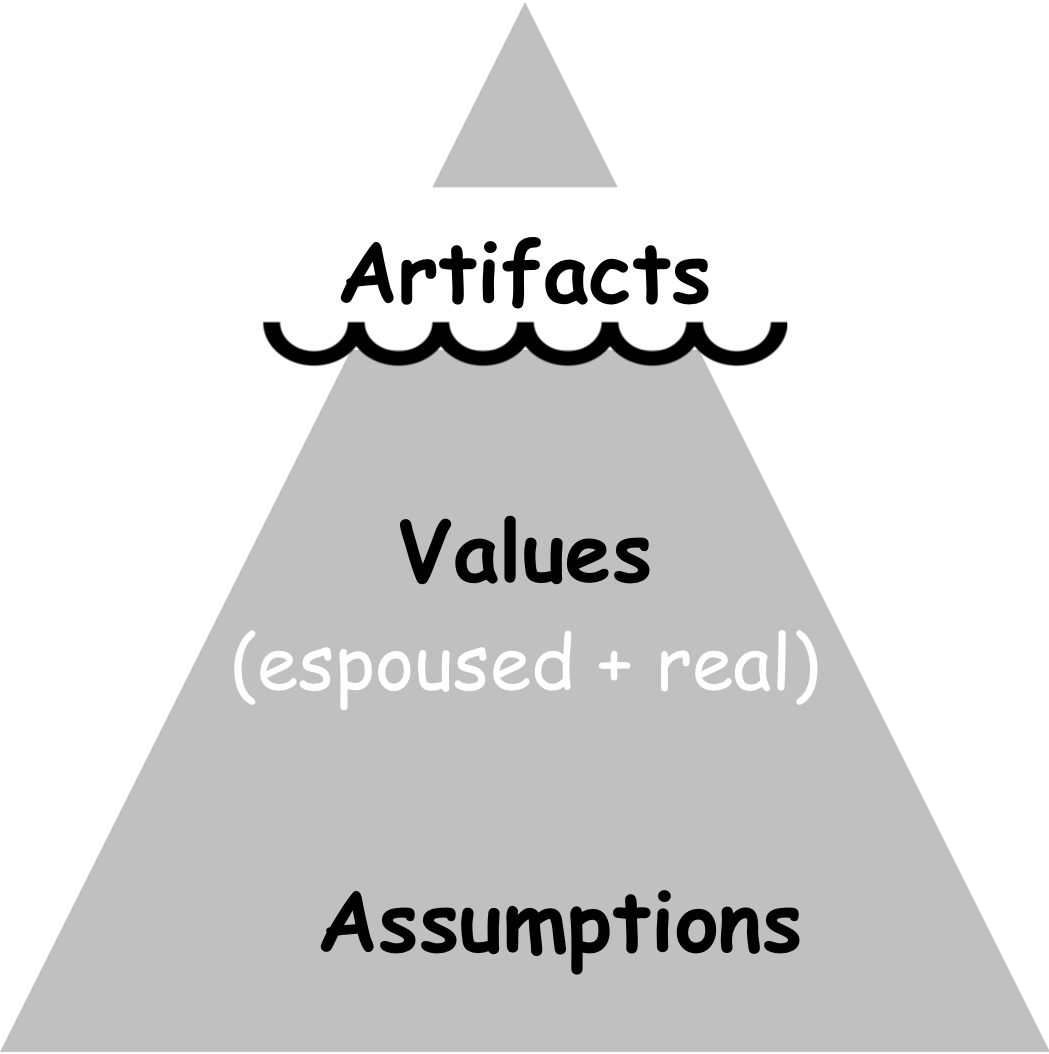

At this point, it’s difficult to decipher the culture without a compass or map. Fortunately, Edgar Schein’s model offers the orientation we need. We can use his Three Levels of Culture to ask questions about any institution.

Figure 4-2. Three levels of culture.

First, what will a visitor see, hear, and feel? Artifacts include architecture, interior design and layout, technology, process, work style, social interactions, and meetings. Who’s the boss? How can you tell? Is there music? Are people talking? What do they wear? Where do they sit? When do they eat? What makes ‘em smile? Artifacts are easy to see but hard to decode. The art on the wall is visible but what does it mean? Why’s it there? Artifacts aren’t answers, but they raise good questions.

Second, what are the mission, vision, and values? How about goals, strategy, brand? Websites, annual reports, and those colorful posters so artfully framed in the lobby offer a place to start, but interviews with insiders are the only way to the truth. Espoused values are hard to miss yet often inconsistent with behavior, which is why we need “informants” to help us see what’s really going on. If teamwork is a core value, why are individuals so competitive? If the organization is user-centered, why doesn’t anyone talk to users? It’s vital to listen carefully as insiders may not know or be willing to tell the truth. Dissonance and its justifications serve as keys to the invisible culture. Entry is earned by paying attention.

Third, what are the tacit beliefs that are taken for granted and non-negotiable? Level three is all about history. What were the ways of the founders that led to success? Are they still valid or holding us back? When we fail to seize the future, it’s often because we’re blinded to the present by the radiance of our past success. Assumptions are the bedrock of culture. They are hidden and resistant to change. As organizations grow, technologies advance, and markets evolve, friction between old assumptions and new realities is inevitable, but people don’t question what they can’t see. This is where an advisor can help. Only insiders can effect cultural change, but it often takes an outsider to sketch the map.

Read more about how everything from code to culture is connected in Peter Morville’s new book Intertwingled: Information Changes Everything. In it, he connects the dots between authority, Buddhism, classification, synesthesia, quantum entaglement, and volleyball.

Image of volleyball player courtesy mooinblack and Shutterstock