Save

DUMBO neighborhood street corner in Brooklyn — Photo by Robert Stribley

A watershed privacy moment in the United States

In July of 2023, a Nebraska court convicted a teenage girl and her mother after the mother assisted her daughter in procuring an illegal abortion. Both had been arrested the previous year in June—the same month that the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. Though they were charged with crimes, which occurred before the fall of Roe, the way the evidence against them was collected proved more broadly alarming in that moment. Nebraska authorities had procured Facebook chat messages between the two from Meta, messages which described the pills the mother had purchased for her daughter and her instructions for using them.

And so, in the post-Roe United States, a whole swathe of the country woke up to a new—or incredibly heightened—privacy concern: How might their online activity be used against them if they determined they needed to procure an abortion, but the state they live in has banned it?

What’s the big deal? I’ve got nothing to hide!

For many people, online privacy has never proven to be a particularly troubling issue for them. “I’ve got nothing to hide” is a pretty common reaction for many, accompanied by a shrug. But, as with many rights, sometimes we don’t understand the need for privacy until it affects us, personally. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, the FTC reported that identity theft in the United States doubled from 2019 to 2020, making privacy issues more relevant to more people than ever. I was a victim of fraud, theft, and impersonation during the pandemic myself. It proved a rather torturous and humbling experience. That spike in identity theft serves as a great reminder that privacy isn’t really about being secretive. It’s about maintaining control over your own information.

As designers, though, we have a particular responsibility. Even if we’re not concerned with privacy issues, personally, we’re not designing for ourselves. If we’re designing with empathy, we’ll consider the needs of people not like ourselves — people with different backgrounds and experiences.

We’re uniquely positioned to take the lead with this issue. But what are some best practices to ensure we’re designing with privacy in mind?

7 Best Practices for Privacy by Design

Let’s look at seven best practices to keep in mind when we’re designing with privacy in mind.

- Avoid deceptive patterns

Deceptive patterns trick people into doing things they didn’t mean to do — like share their contacts or other personal information. These moments can really undermine users’ privacy. Read up on deceptive patterns and don’t allow them into your designs. Harry Brignull’s work on deceptive patterns is a great place to start.

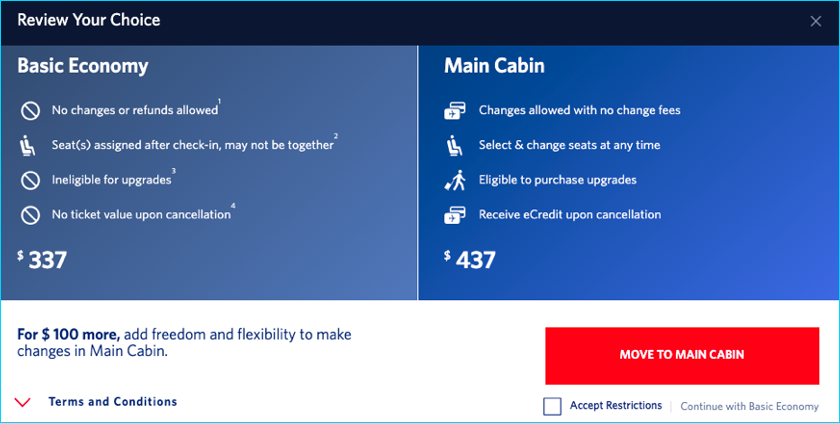

In the above example from a major airline, the customer has already chosen Basic Economy but “Move to Main Cabin” — which costs $100 more — is placed as a large red button right where you would typically expect to find a “Next” button. To keep your first selection, you have to click on “Continue with Basic Economy” — the smallest, most low-contrast copy on the module.

Patterns like this already interrupt users’ experience but they also undermine people’s trust and even anger them, too. Here the pattern is used to trick people into an upsell. But similar patterns have been used to trick users into sharing their contacts with a platform, who are then “friend spammed”—a mortifying outcome for any individual, for sure. And a significant privacy issue.

The above deceptive pattern could be easily fixed. How might you go about designing it differently?

2. Maintain transparency

Be transparent — not only with what data is used and why, but also with who it’s given to. People may not realize that a single site shares their data with so many third parties. I once looked at the cookie behavior on one UK news site and determined that they shared user data with over 600 third parties. Do you think most visitors to the site understand that? I doubt it.

Additionally, customers want to know that their personally identifiable information (PII) is safe when handing it over. PII can be misused for identity theft, and you don’t even need PII to identify a specific individual. One study showed that 87 percent of the U.S. population can be identified as individuals by just their date of birth, gender, ZIP code. Those items aren’t even considered PII. Imagine how much damage a bad actor can do with just three pieces of PII. The more personal information someone can collect about an individual, the greater the chance they can do a lot of harm. Consumers deserve to know what personal data points are being collected and who they’re being shared with. And they should have the opportunity to consent to sharing that data.

3. Use language with care

In 2019, The New York Times studied 150 privacy policies from various tech and media platforms. (Imagine the ordeal of conducting that study!) They described what they found as an “incomprehensible disaster.” They described AirBnB’s privacy policy as “particularly inscrutable.”

Language can be used to intentionally, obscure privacy issues and to confuse users. As The Times found, AirBnB used vague language “that allows for a wide range of interpretation, providing flexibility for Airbnb to defend its data practices in a lawsuit while making it harder for users to understand what is being done with their data.”

Of course, we should not only avoid legalese and jargon within terms of use and privacy policies: We should be sure to use clear language with marketing copy, too. That means writing to the appropriate audience level. Did you know that 50 percent of adult Americans can’t read a book written at the 8th-grade level? That’s why the Content Marketing Institute recommends writing for about a 14- or 15-year-old. If you’re not writing to that level, you may be making it difficult for your customers to digest important information.

4. Provide tools for protecting data

Some companies may offer a nod towards providing privacy-related tools, but even these often default to making people’s data public. For example, website cookie patterns are often presented as if they’re assisting users with their privacy but actually trick them into accepting cookies and bury the details of what data is being shared with whom. Give users options to control their personal information. If you’re working with a large corporation that handles a lot of personal information, you might even advocate for a privacy microsite or toolbox to highlight these features.

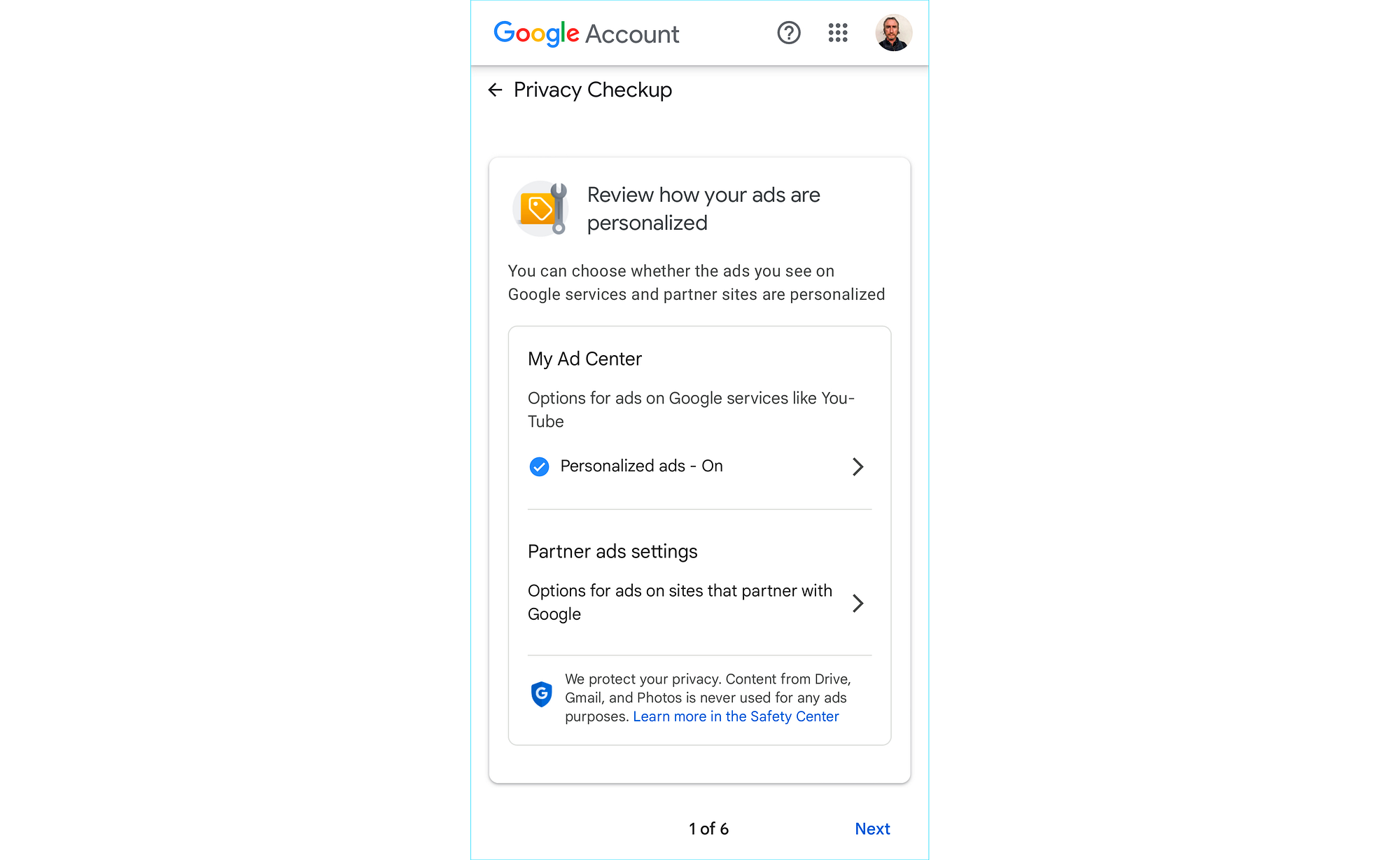

Google offers a “Privacy Checkup” with high-level descriptions of how your personal data is being used and why. This overview links to specific Privacy Controls, which allow you to adjust how that data is accessed. You can turn off activity tracking, location history, your YouTube history, your Google photo settings, check which third parties have access to your account information, and access other key settings all in one sort of privacy dashboard. Facebook offers a similar privacy checkup, too.

5. Ensure privacy features are discoverable

Important information about how your personal data is used shouldn’t be placed in 8-point font, buried in the Terms & Conditions, hidden in the footer, or several levels of navigation down deep in your app— and yet, that’s often where we find it. This content should be offered contextually and easy to find.

For example, California’s Opt-Out Icon draws attention to features, which allow consumers to opt out of sharing their personal information with third parties on a website.

Making privacy information contextual and easy to find also means that you highlight it at two crucial moments:

- Onboarding — Explaining in detail how you use people’s data when they’re using your app for the very first time.

- “Just in time” alerts — Alerting users in the moment — when they’re about to share data in a new way — even if they have a history of using your experience.

6. Remind users of privacy features

Remind users regularly about their privacy options and actively encourage them to take advantage of them. This practice acts as a good faith measure and can instill trust in consumers that the brand has their best interests at heart. Offer these reminders proactively, and regularly.

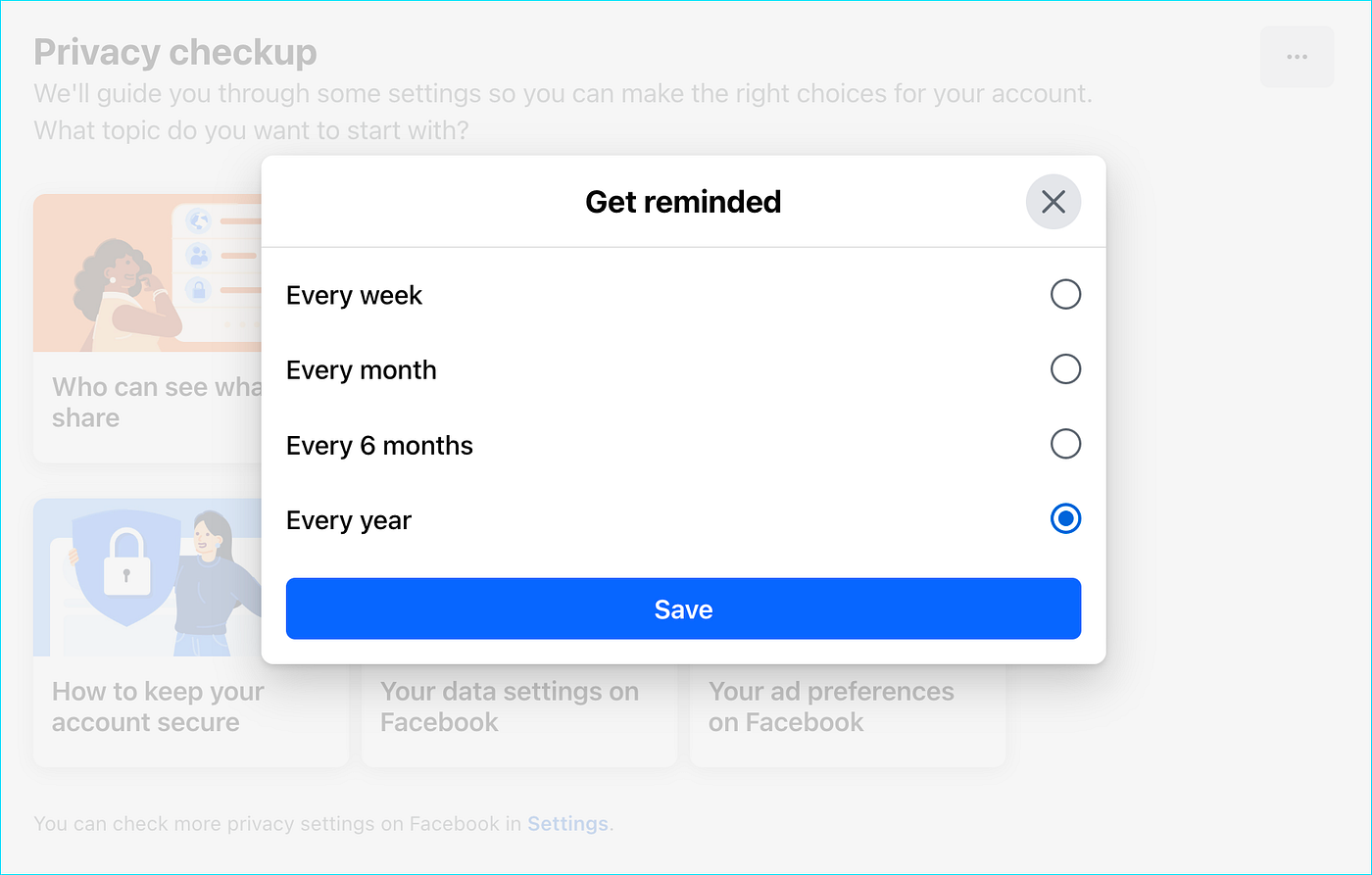

Here, for example, Facebook allows you to set reminders to perform a privacy checkup on their platform every week, month, six months, or year. You do have to know where to find these settings, however. Ideally, Facebook would consider emailing users periodically to remind them of these helpful features.

7. Never change privacy settings without letting users know

Alert users in advance whenever changes need to be made to your experience’s privacy settings. Also, be sure to let them know how they can adjust their settings to avoid potential privacy issues. Even better? Make sure any settings are set to “private” by default. Avoid making changes, which may endanger users (people!) within vulnerable or at-risk groups. Ensure you practice good user research and inclusive design, so you’ll be aware of the needs of these groups.

A few years ago, Facebook made users’ page “likes” visible to everyone by default, as well as other content, which consequently may have outed some people in the LGTBQIA+ community or revealed people’s personal, political, or religious beliefs.

When I asked an employee how Facebook justified this change, they responded that the company valued transparency and wanted people to be open about their interests. The company’s founder Mark Zuckerberg had even famously proclaimed that privacy was no longer a “social norm.”

Many at-risk individuals would disagree. We shouldn’t make decisions about other people’s personal data and interests on their behalf. Instead, we should seek their explicit consent.

Why should your clients care?

It does no one any good, if we’ve adopted this thinking around privacy by design, but our clients haven’t. So, how can we bring our clients around to the idea that they should maximize their concern for their customers’ privacy, too?

Discussing privacy issues with clients can be sticky. But ignoring privacy issues for short-term benefits can lead to greater long-term costs.

Brands — our clients — should consider the privacy of their users’ data, their content, even their browsing behavior for their customers’ benefit and safety. But, let’s be real: They will also likely do it for their own personal and financial self-interest.

Given that reality, when reminding your clients of the importance of respecting their customers’ privacy, you can focus on the following themes …

- Civic responsibility — Encourage your clients to exercise leadership in respecting users’ privacy.

- Reputation management — Remind them that their brand can be tarnished if they fail to respect people’s privacy.

- Site abandonment — Users may leave their site for another if they perceive their privacy is being undermined in the moment.

- Loss of user base — If the experience proves bad enough, they may find customers abandoning their business altogether.

- Financial impact — Increasingly, emerging legislation and regulations may mean fines for companies, which ignore users’ privacy.

Remember, privacy isn’t an issue of secrecy. It means allowing people consent and control over their own personal information. As we strive to practice truly user-centered design, we learn to value the principles of empathy and inclusion. I’m convinced that leads us to keeping these best practices in mind. That way, we can maintain vigilance against invasive design practices, which attempt to undermine people’s privacy.

Additional Resources

An abbreviated version of this essay is available in pamphlet form here. If you’d like me to present on this topic in much greater detail for your company or organization, feel free to contact me at Technique. I also hope to develop this material into a book complete with compelling case studies and helpful, privacy-minded solutions.

Robert Stribley is a user experience design professional with over 20 years of experience. He worked at Razorfish and Publicis Sapient before recently starting his own small company, Technique. He teaches UX design at the School of Visual Arts, and speaks regularly on the subjects of user experience design and privacy by design.

- The article delves into the rising importance of addressing privacy concerns in user experience design, offering insights and best practices for designers and emphasizing the role of client cooperation in safeguarding user privacy.