Save

Despite the obvious cultural differences between Chinese people and Americans, when it comes to technology—and in particular e-commerce—we want a lot of the same things as users.

One thing marketing in China for ten years will teach you is that the Chinese are motivated by the same Maslovian hierarchy of needs, and respond to all the same emotional triggers. Chinese consumers are not driven, first and foremost, by their ancient culture—nor are price points their highest consideration. They are also aware enough of the value of Western products that “educating” them about them is far less effective than communicating authenticity.

This universality holds true for UX, as well, though you might be asking: “But why, then, are Chinese websites so different?” The short answer: they’re not so different anymore. The important answer: it’s the systems in China that make things different, not the people.

Consumer protection laws were virtually unheard of in China until fairly recently. There are no better business bureaus and no small claims courts, creating a Wild East e-commerce environment. This lawless landscape coupled with draconian Ministry of Information oversight, has resulted in the Chinese Internet of today.

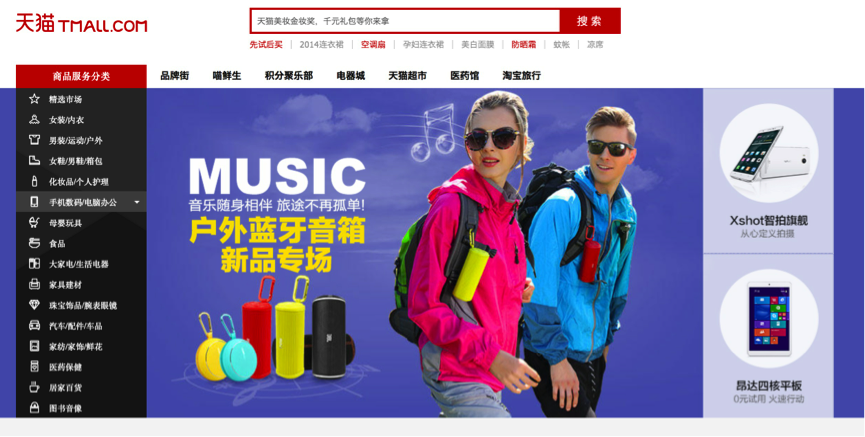

Today’s Chinese net is consolidating into massive e-commerce platforms, focused portals, and cross-functional mobility. As each space becomes increasingly omnichannel, the lines get blurred, but not the principle—the Chinese want what we want online: convenience, transparency, and constant image-driven diversion. A look at China’s biggest ecommerce platform, Tmall, illustrates these principles.

West is Best

For the shopper who knows what he or she is looking for, the search bar takes top position—on Tmall’s home page, next to the logo. However, for the millions browsing Tmall at any given moment, the left-hand menu bar is the typical starting point, dividing China’s preferred online B2C destination by product category.

Two important things to notice:

- Hover navigation over each item on the bar reveals its own slider of featured product advertisements, impact-image driven, with a brief promotional call-out.

- Most of these ad banners contain at least one word of English, and many have non-Chinese models in them, as shown below.

The first feature should help dispel the myth that the Chinese prefer busy landing pages crammed with Mandarin characters. Anyone browsing through the sliding banners will also notice a distinct lack of images pushing family values or social status, two touch points suggested ad nauseam as critical for appealing to the Chinese consumer.

Rather, the second feature shows the crucial touch point for driving engagement: Western emphasis. Many of the banners contain English words more difficult than “music,” pictured above, and are not readily comprehensible to the average viewer, for whom compulsory English education has been more burden than benefit.

When designing for Chinese users, dispense with notions of insurmountable cultural barriers

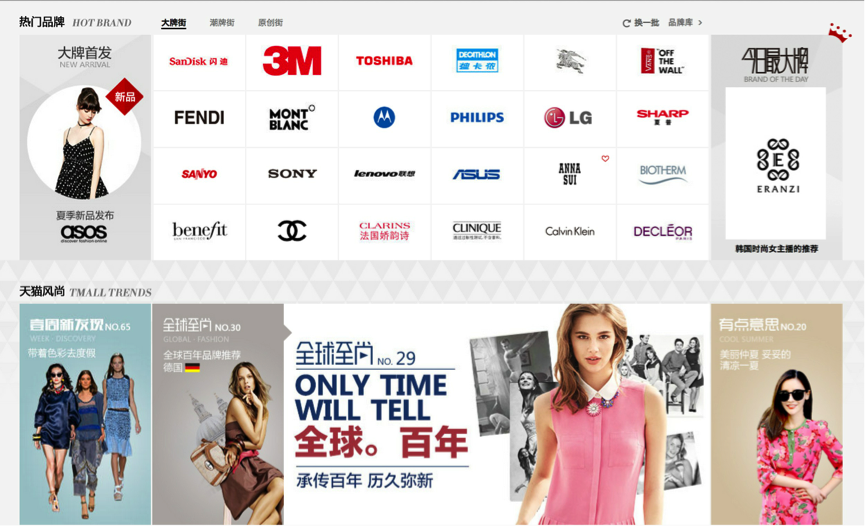

But the idea that these products, and the benefits they confer, are associated with the West is essential. The notion of “Made in China” is for Walmart, not Chinese online B2C shopping. Look at the next section under the navigation bar and sliders: A host of popular non-Chinese brands to explore further (possible exception: San Disk, made in Taiwan) and non-Chinese models and English text.

The takeaway: Western brands have a distinct advantage in China’s B2C marketplace, in that Chinese perceive them as inherently superior to brands coming out of China. The non-Chinese models and English text underline the desired Western provenance.

There is a Chinese platform for buying made-in-China: Taobao, Tmall’s C2C sister. Many Chinese vendors sell more niche Western products here as well, but for fashion, retail electronics, and the other categories displayed in Tmall’s top left menu bar, international appeal is a must, and nothing appeals like a known Western brand adapting itself to the TMall ecosystem—responsible for half of China’s $300b online B2C market in 2013

Seller Beware

Alibaba founder Jack Ma tamed China’s aforementioned Wild East e-commerce environment by laying down the e-law with indelible comments, user ratings, and iron-clad terms and conditions.

Although the latter cloned the former, the differences between the product page layout on Amazon and Tmall show how China’s low-trust environment obliges vendors to rely as much, or more, on their reputation as on the reputation of their products and pricings—with far more copious evidence to speak to the authenticity of their wares.

After a search on Amazon for “memory card”, and selection of a top result, we arrive at a product page that the western shopper has come to expect as standard, where low price, bullet point product description, and some express delivery options suffice to form a fairly solid basis for decision, before scrolling to reviews:

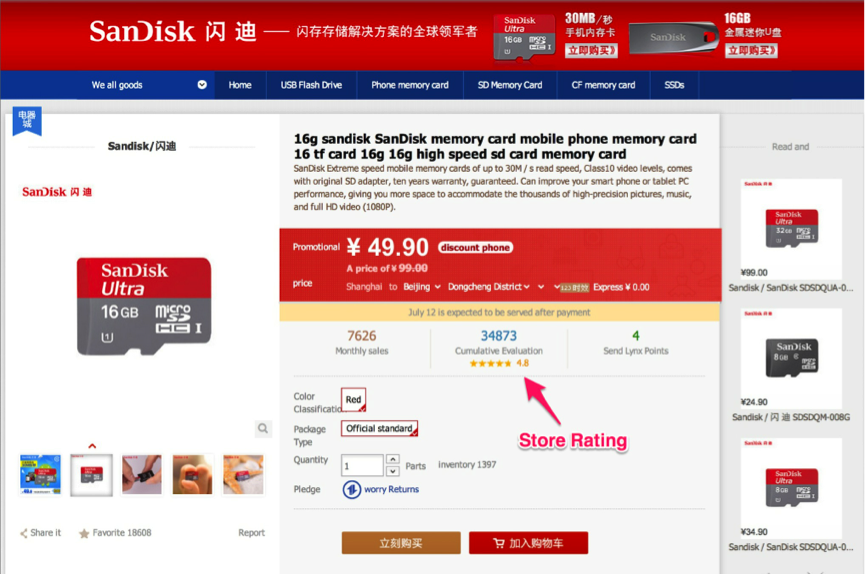

A similar search and product selection on Tmall reveals that it’s incumbent on the seller to provide a comparative wealth of information and proof before the reviews begin.

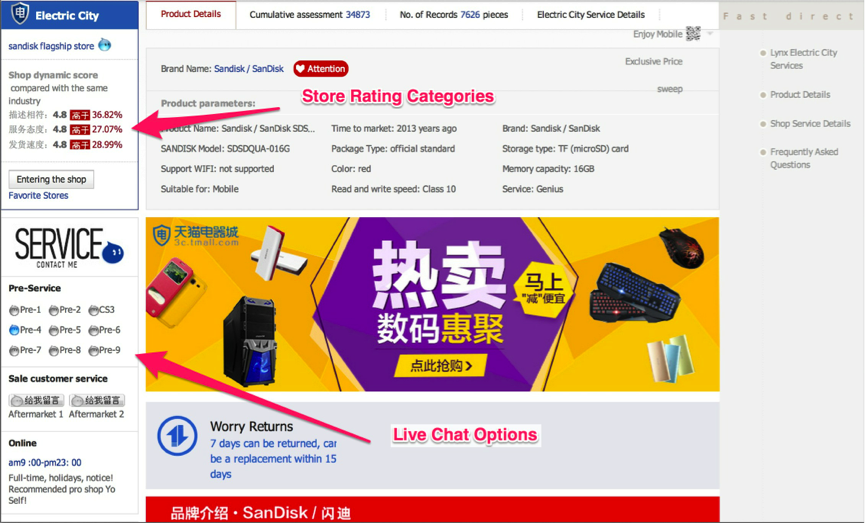

The top of the product page looks much like its Amazon analog, but notice the store rating featured below the number of reviews:

Store ratings are based on a five-point system. This store’s rating of 4.8 is respectable, but good ratings only justify the scroll down to a more thorough investigation of the evidence:

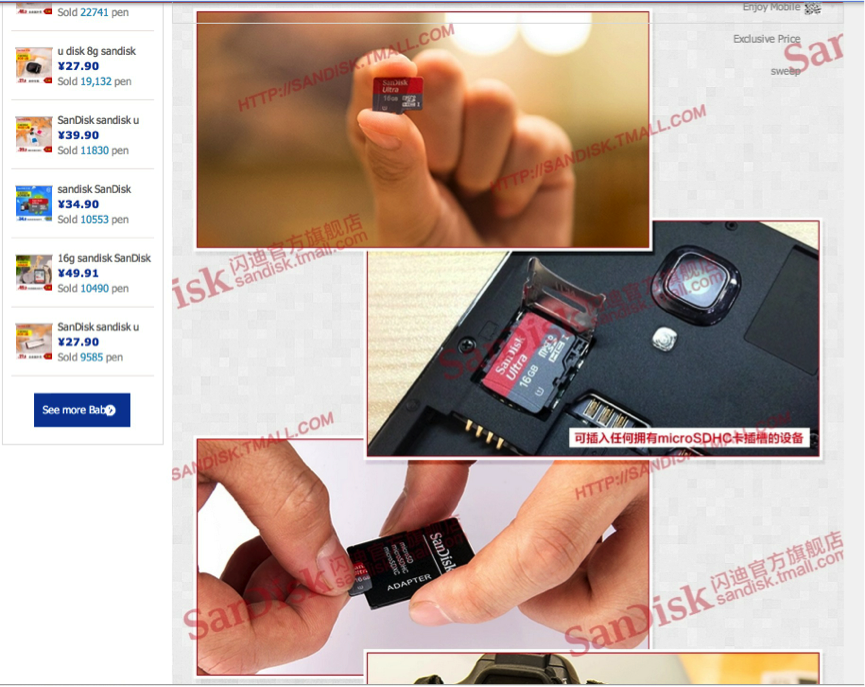

Various pictures of how the product should look and function in context:

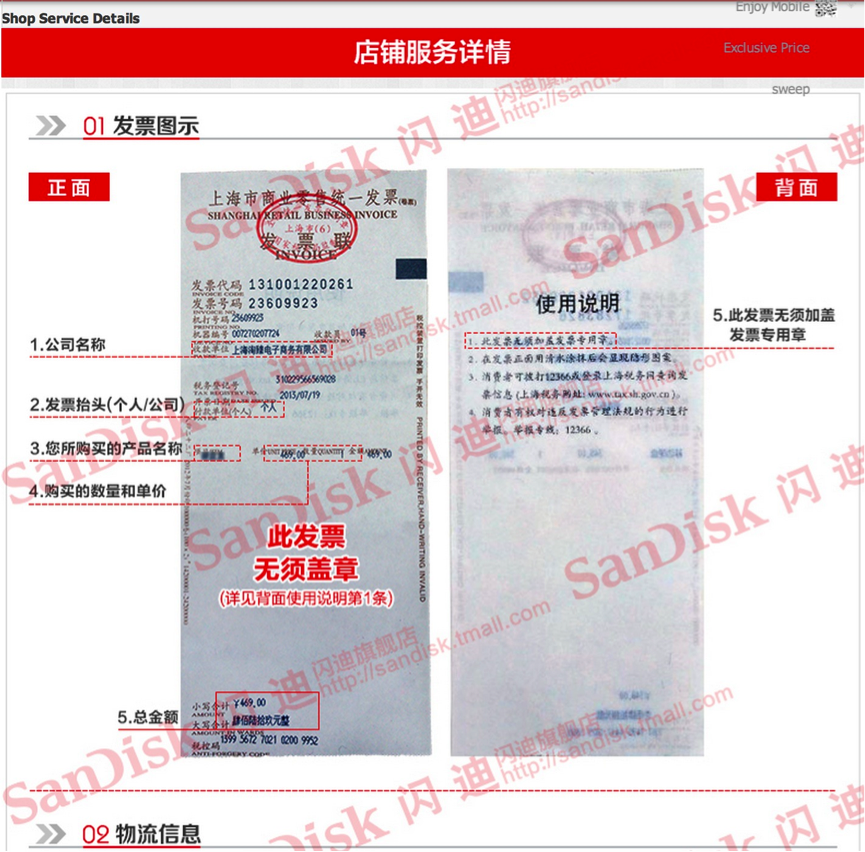

Scans of what the official receipt will look like:

Breakdown of the store’s ratings for service and delivery, as well as numerous live chat options, even for after-service, both on the left of the pic below (pages translated automatically, not accurately):

Other product pages have detailed pictures of the packaging, as well as scans of accompanying brochures—anything and everything that will help to convince a potential consumer that this vendor, unlike so many others, is an honest shop selling an honest product.

Conclusion

So when designing for the Chinese user, dispense with notions of insurmountable cultural barriers. Instead, focus on communicating Western quality and authenticity, and emphasizing that what they see is what they get. These guidelines serve not only for implementing Tmall stores, but any effort in the Chinese ecommerce ecosystem, for which Tmall is the paradigm.

Ernie Diaz

This user does not have bio yet.