My life as a writer began on paper. Some of my earliest memories are of writing short stories on worksheets in elementary school. By the time I was in high school, I was filling marbled composition books with obscure confessional poetry (none of it embarrassing to revisit now). In college, I started modeling my behavior after downtrodden lions like Henry Miller and Charles Bukowski, drinking beer and scribbling in notebooks with worn down pencils late into the night.

I was studying journalism and had the good fortune to take classes from a grizzled old newsman who pounded into our heads the notion that newswriting was a trade, not some ego trip. Plumbers have their tools and reporters have theirs. Both jobs rely on understanding the how systems work. The plumber knows how to route water and the newsman can dig up facts and fit them into the inverted pyramid. The lesson: Writing is not glamorous. Writing is work.

Most of my literary idols—from Hunter S. Thompson to John Fante to Mike Royko to Hemingway—romanticized the hard work of writing. Living the experiences that gave way to the stories was as laborious as getting them on the page with gritty single-finger punches on a typewriter, the splendid machine at the center of it all.

From a design perspective there are few products as romantic and pure; a weighty contraption built to create with a very obvious purpose. Even ugly typewriters are beautiful. When my girlfriend at the time bought me an old Royal, I teemed with excitement over all of the things I was going to write with it: novels, screenplays, and epic poems. Then I started using the thing and realized just how much work writing could be.

Bourne to Type

Around the same time, I came across Scott Bourne in the pages of skateboarding magazines. Known in skate circles for his heavily tattooed arms—both of them almost completely black—his penchant for doing burly things on and over questionable terrain, and the raw and personal writing that appeared in his “Black Box” column in SLAP magazine, the dude had swagger. An outspoken critic of many aspects of life in America, nobody was too surprised when, in the early 2000s, he moved to a remote village in France to write a novel.

He wrote the whole thing on paper. He had no computer, just a typewriter, some pens, some notebooks, and a wall where he taped pages. It took years of editing, but he eventually finished a semi-autobiographical book about his time spent in San Francisco in the ’90s, A Room With No Windows. He reluctantly sent me an early draft of the book on a CD-R, demanding that I print the whole thing out and read it as it was meant to be consumed: on paper. It’s worth mentioning that these CD-Rs came in a telltale envelope, ornately decorated and stamped shut with his own personal wax seal.

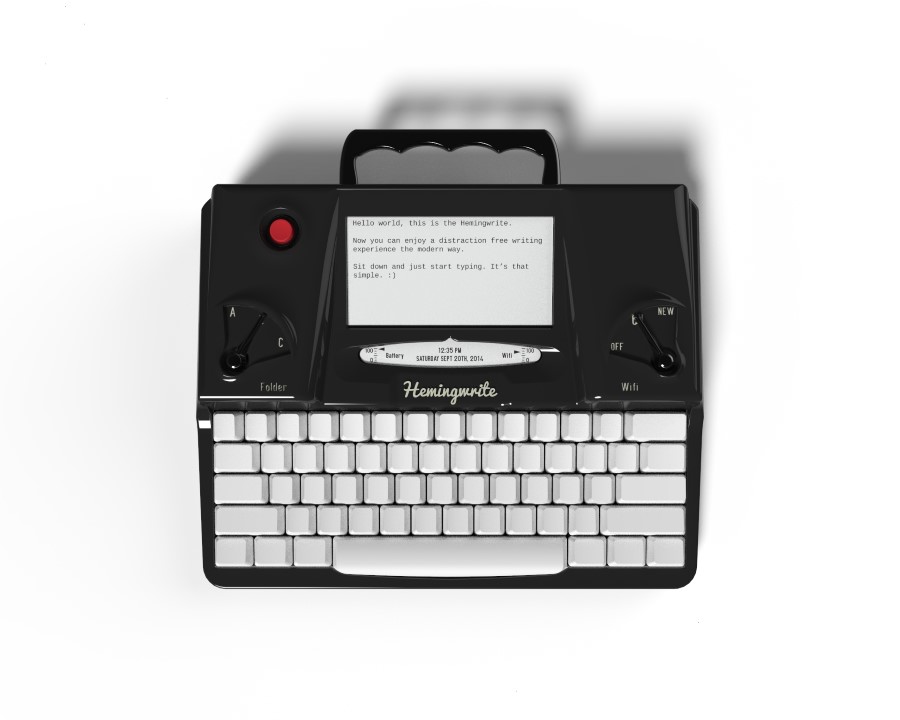

When I saw the Hemingwrite a few days ago—a lovely E Ink typewriter described as “the Kindle of writing composition”—I thought of Scott. I’d pestered him with this type of thing before. Back in 2010, I sent him a link to OmmWriter, an app that creates a full-screen writing environment on your computer designed to reduce distraction.

“i will check out ommwriter … but i am a man on a machine.” He wrote back, along with a link to a video a friend had made of him skating and talking about his typewriters.

Admittedly, I was baiting him, and I didn’t even have to open his return email to confirm my suspicions that he wouldn’t think much of the product. He’d changed the subject line from “Hemingwrite” to “Hemingwrong.”

“As for the Heminwrite, honestly that thing just looks like another hipster device marketed to prey on people’s weaknesses. It’s another magic pill to give them discipline, and I can tell you that if you can’t cut off your phone or your computer for a few hours a day to work on a novel, this thing is not going to help you. Writing is all about discipline and if you don’t have that from the start … there isn’t any little gadget that’s going to do it for you. It’s solitary work!”

As for his solitary work, Scott has another full-length novel with an editor, a book of short stories releasing in early 2015, a screenplay, two children’s books, a 100-page poem being illustrated by Todd Bratrud, two books of poetry, and 300 pages of notes for his next novel—all on paper.

Technology Responds

While I share Scott’s skepticism about a stylish device being able to shake someone into the habit of sitting down and writing, I do like the look of the Hemingwrite. I like the understated nature of the screen and the fact that it has levers and knobs. It looks like it would be a pleasure to use, but it’s basic functionality reminds me a birthday present from my parents back in my college days: the AlpahSmart Pro.

Writing is all about discipline … there isn’t any little gadget that’s going to do it for you

A product of Intelligent Peripheral Devices, Inc., founded in 1992 by two former Apple engineers, the AlphaSmart Pro is more or less a digital typewriter. You turn it on and type, filling up eight files capable of holding different amounts of text. When you’re ready to move your work to a computer for editing and printing, you open a Word or Text document, plug the AlphaSmart into the keyboard port and hit “send.” The AlphaSmart barfs your words into the document as though someone was typing them super, super fast.

Left to right: correspondence from Scott Bourne, my Royal typewriter, and my Alphasmart Pro

It was a wonderful companion in the days before laptop computers. Designed to give you the ability to create virtually anywhere, it went with me on assignment, on city buses, and even into coffee shops. It was meant to save you from the labor of transcribing handwritten notes or lugging around a heavy typewriter and reams of paper, and it delivered.

The Hemingwrite, on the other hand, is designed to save you from yourself, by reducing the chance that the ubiquitous Internet will distract you. As someone who has shit away countless hours conducting “research” (how can you write the novel of your youth without watching 58 videos of the songs you liked back them?) I get it. I can easily picture myself typing away on a Hemingwrite in an Adirondack chair at the end of a dock somewhere. Still, the fact remains, if you aren’t willing to sit down and put in the work, there’s not a gadget out there that will make you a writer.

As Jason Epstein wrote a few years ago in The New York Review of Books (and thanks to Scott for sending this along):

“The difficult, solitary work of literary creation, however, demands rare individual talent and in fiction is almost never collaborative. Social networking may expose readers to this or that book but violates the solitude required to create artificial worlds with real people in them. Until it is ready to be shown to a trusted friend or editor, a writer’s work in progress is intensely private. Dickens and Melville wrote in solitude on paper with pens; except for their use of typewriters and computers so have the hundreds of authors I have worked with over many years.”

Nabakov, Meet Siri

What’s interesting to think about is ways that technology might actually change the process of writing. Think of Nabakov, who often wrote notes on index cards that he later dictated his wife, Véra, who would type them up. There aren’t many partners loyal enough to take constant dictation—and it’s absurd to suggest that technology could ever replace a devoted editor and writing assistant like her—but as voice recognition technology matures, it will certainly be possible to dictate a creative frenzy of ideas to an app that can transcribe them into pages for later editing.

Why even bother to write them down? If you were able to tag individual sessions with things like “conflict emerges; end of act one” the app might even structure your work for you. You could write a book while walking through the park.

This is an example of how technology might fundamentally change the act of writing, eliminating some of the solitude and stasis associated with they way writers work today. It would surely also gouge the quality of the work in immeasurable ways and would not change the grueling editing process. The bigger issue is the way technology might change the essence of what it means to write, making it veer closer to something bland like content creation.

Writing needs to be hard to be good. So whatever the future holds, for now, I’ll continue sitting alone with my thoughts, my laptop, and some printer paper, wishing I had the fortitude to use a real typewriter.