In the next seven minutes or so, this article hopes to convince you that our current notion of UX design mistakenly focuses on experience, and that we should go one step further and focus on the memory of an experience instead.

Studies of behavioral economics have changed my entire perspective on UX design, causing me to question basic tenets. This has led to ponderings like: “Is it possible that trying to create ‘great experiences’ is pointless?” Nobel Prize-winning research seems to hint that it is.

Via concrete examples, additional research sources, and some initial how-to tips, I aim to illustrate why and how we should recalibrate our UX design processes.

Imagine Two Scenarios

Imagine you’re on holiday, traveling overseas. Excitedly, you board your flight. You slip into your seat. You flip through the entertainment system and perhaps watch a movie. Some uneventful hours later, you land at your destination. You debark and are relieved to retrieve your luggage, fully intact. Then, you head into the unknown! You manage to navigate yourself to your hotel. Luckily, a room is reserved for you. You enter, drop your keys and luggage for a quick inspection. Finally, you let yourself fall onto the bed for a moment of rest. But, you are curious about this new country you’re in, and you don’t wait long before heading out again…

Chances are, this travel-scenario will feel somewhat familiar to you. Perhaps it even brings back memories of a specific vacation. Most vacations tend to be unforgettable experiences. The experience of traveling, after all, is the core reason why we travel, no?

How would you retell the story of an Amazon visit?

Now imagine you’re at home, relaxed and having a look around Amazon. You quickly find what you came for and add it to your shopping cart. Then, your attention is drawn to another item. You skim its page. Perhaps you read a review. You decide to add it to your shopping cart as well. Then you proceed to checkout. A few buttons later, your order is made. A few days later, your order arrives, fully intact. All is well.

I’ve just described two experiences—very different in nature, but both experiences. And thus, both, in theory, could be designed. And both lead to the same question:

Should We Focus on User Experience?

When thinking back about an experience (a voyage or an Amazon purchase, for example) are we truly capable of accurate mental replay? After all, we can only recall what we encoded into memory. If an experience was great, will we remember it as such? And if we remember an experience as a positive one, did we truly experience it as such at the time?

And if these two perspectives do diverge, then, which one is most important: the experience, or its memory? Ironically, in terms of user experience, only memories matter. I’ll back this claim up with help from Nobel Prize-winning research about how we experience the world around us that has ramifications for UX design; not just on a philosophical level, but on a practical, day-to-day level as well.

Perhaps you’ve heard it said: “If a user needs to fill out a form, it should go as quickly a possible.” Well, it turns out that isn’t always true. The amount of time it (or anything) takes is entirely irrelevant, because we simply do not encode time spans into memory. The way we experience things and the way we remember things are truly two separate cognitive processes guided by different laws.

The inconvenience for UX is that all of our decisions are made based on memories. Unfortunately, UX design focuses on the experience part, while a great experience does not necessarily get remembered as such. UX design should be a function of the memories it creates.

We should design for memories, but obviously we cannot design actual memories. We can only hope to imprint positive memories via the UX we design, day-to-day. But for our UX design processes to effectively refocus on the true end goal—the memories, not the mere experiences—we should first thoroughly understand how our memory works.

Pioneering Academic Research

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman is the first non-economist ever to have won a Nobel Prize in Economics (2002). Kahneman is also noted as the founding father of behavioral economics. In his long career, working primarily at Princeton, he has performed truly groundbreaking research into many of our psychological quirks (endowment, priming, prospect theory, etc.).

In a talk at TED, he highlighted some difficulties encountered when researching happiness and mental well-being that lead to the observation that we all have two distinct selves: our experiencing self and our remembering self. These two selves are very, very different, acting almost as opposites which are “made happy by different things.” The core difference is that all decisions are made by our remembering self. Our experiencing self “has no vote whatsoever.”

Prof. Kahneman describes how we choose between memories of experiences, not experiences

That TED video struck a chord with me. For, was it possible that UX design is kind of missing the point? Is creating “great experiences” pointless?! The notion changed my entire perspective on UX design. I started researching this further and got a chance to speak about it at EuroIA in Paris and the IA Summit in Denver with a presentation titled “On why we should NOT focus on UX.”

Kahneman obviously didn’t mean to study UX design, but it’s striking how his conclusions apply to UX. A return visit to Amazon, after all, is a conscious decision. So is recommending something to a friend. Neither decision is made by our experiencing self, but by our remembering self. But what makes these selves so different?

First, it’s important to understand the concept of “psychological present,” or the “now.” It has been described as “the duration of an experiental process and estimated (…) to last between 100 milliseconds and approximately five seconds with an average length of two to three seconds.” (See “Spontaneous confabulations, disorientation, and the processing of ‘now’,” by Prof. Armin Schnider.)

The “now” is distinguished from periods shorter than 100 milliseconds, “which are perceived as instantaneous, and from periods longer than five seconds, which are thought to involve long-term memory.”

Therefore, if something does not get encoded into memory in the time frame of two to three seconds, it is lost forever. In fact, most of what we experience is lost forever since we encode only a tiny fraction of specific details.

Think back about that holiday scenario, how much do you truly remember of any past vacation? It will only be very specific events. By definition, it is impossible to recall the experience of traveling. The problem is that our experiencing self lives in the “now” and those experiences are extremely volatile. Thinking back, we can never judge an experience, only the picture constructed by the bits we remember.

Let’s try to apply this to a concrete issue: When designing, should we rely on “conventions” or not? Conventions are great for making something blend in; making it fit with what we consider “normal”. However, convention-based design also tends to become unremarkable/unmemorable.

BBC sketch parodies phony discounts; or how our knowledge and framing influences decision making

In an almost dictatorial way, our remembering self selectively picks what parts of an experience it wants to remember. And later, it makes its decisions based on those memories. But, the impact of memories—or knowledge as a type of memory—on decision-making works the other way as well. As Dan Ariely, another behavioral economist (MIT), points out in his book Predictably Irrational, “Knowledge does not simply inform. It changes the experience. It realigns your senses.”

A silly sketch from The Armstrong & Miller Show (BBC) beautifully illustrates how missing knowledge about the full price of garden pots can make people vulnerable to irresistible sales. (Think Groupon.) When designing for memorability instead of the mere experience, it is important to take into account your audience’s presumed existing knowledge, as it will color the experience. But most important will be to first carefully pinpoint which elements you would like most to be remembered (like your USP, or the price tag) or forgotten (like the experience of a long annoying form, or the price tag).

Next, let’s try to picture how focusing on memory instead of experience would impact the design process.

Practical Implications and Applications

The idea that attention to memory is important is not new. Don Norman has talked about it and David Maister (The Psychology of Waiting Lines) touched on it way back in 1985! Still, the idea that we should focus on memory instead of experience hardly seems mainstream.

While shifting the focus to memory, UX design will still remain important, but it will require a different kind of UX design, focused on the memories it aims to impress. Too often, I hear design discussions stop prematurely, sticking to the creation of “great experiences” for the sake of the experiences—like recipes explaining how to buy all ingredients, but not how to prepare the actual dish.

Left hungry for practical guidelines on how to design for memorability, there’s no choice but to start research on how our memory works. It’s a fascinating, but complex domain, and the model presented by Chip and Dan Heath in Made To Stick gives a great taste of how to make an idea memorable, or “sticky,” using six criteria:

Simple

Umbrella Today? and, obviously, Google Search are great examples of simplicity. Seems a no-brainer, but as any UX designer with some experience knows, simplicity is extremely hard to execute. It takes discipline, team alignment, and strong management to truly remain focused on the core essence.

Unexpected

If something is unexpected, chances are it will attract attention because it doesn’t fit with what we consider to be “normal”. The resulting curiosity may then persuade someone to spend a bit more time examining it. Take Silverback‘s original leafs parallax trick, or many examples mentioned on Little Big Details, as evidence.

An extra benefit could be that those who have discovered the “Easter egg” may feel they are in the know, and may get an urge to share that secret.

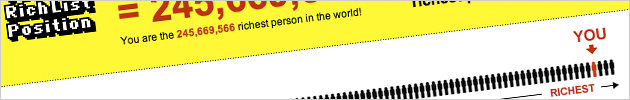

Concrete

As Einstein put it: “If I can’t picture it, I can’t understand it.” Concreteness is extremely important and is closely related to the issue of existing knowledge. For maximum cognitive ease (and encoding), is it best to explain and present the subject using concepts or metaphors your audience is already familiar with. Global Rich List does a good job of this, as do well-made info-graphics.

Credible

Already relatively established, perhaps largely thanks to the work of Stanford’s BJ Fogg, credibility plays a particularly critical role in the early stages of an encounter, when we, in a matter of seconds, conclude whether to invest additional energy or bluntly move on. Here, aesthetic design plays a major role. You can see credibility successfully established at Kickstarter or any mature e-commerce platform citing respected clients or as-seen-in media.

Emotional

Plenty of great articles exist on the why and how of emotion in design, most notably perhaps by Mailchimp’s Aarron Walter in his book designing for Emotion. But why emotion? Because an emotional response tends to leave a deeper, visceral impression, making it more likely to be memorable, like this Virgin Atlantic safety video.

Stories

Good storytelling is perhaps most important of all, because our remembering self is a storyteller! Experiences are recalled as stories. Memories are stories! Kony 2012, or Toms Shoes both do a solid job of telling their stories in a way that has proven memorable.

Kahneman also stressed very much the importance of the “story about an experience” and lists the parts that define a story in memory:

- Changes

- Significant moments

- Endings (very important; see also the well-known peak-end rule)

Take the example of a user filling out a form or buying something on Amazon. The deciding factor for the remembering self, who will afterwards decide to return or promote your idea, will not be the time it takes, but what will happened during changes (“Next”), significant moments (“Payment”) and endings (Confirmation, delivery, follow-up, etc.).

It is clear that a thorough grasp of the art of storytelling will help to produce memorable experiences.

Conclusion

A bit like Donald in this 1938 Disney short, we all have 2 selves, and they are profoundly different

We all have two selves. Not necessarily in terms of good versus evil, but research has unmistakably shown that Self #1 experiences, while Self #2 remembers, and that it’s an either/or story. They can never do both. The ramifications for UX design, then, are profound, as UX tailors to the needs of Self #1 while all decisions within the experience—like: “Let’s do that again!”—are made by Self #2.

Memories are of the utmost importance. Creating “great experiences” for the mere sake of the experience seems insufficient and premature. Attempting to instill fond memories will be possible only via UX design, but it will require a different kind of UX design, that is laser-focused on the memories we hope will stick.

Epilogue

Next action step? For a true understanding of our memory, head to the library (or Amazon). Some book tips: Moonwalking with Einstein, Mind Hacks, The Advertising Concept Book, Believe Me, Thinking Fast and Slow, and the aforementioned Made To Stick. I wish I could offer a list of “10 Ways To Design User Memories” but it isn’t that easy. Still, my IA Summit talk also offers some additional examples and background info.

Droped ice cream photo courtesy Jon Wilson