Recently I posted about Co-designing containers (labs, accelerators, programs, workshops) for transformation, Surfacing innovation in a bureaucracy with such containers, and what we can do outside (or in the absence of) such containers. This post will cover why designers and facilitators need to facilitate internal and external transformative experiences for accelerator or innovation lab participants.

There are a few angles to cover here: One is from the perspective of the program provider (the innovation team/facilitators); Two is from the perspective of the participants returning to their departments; Three is from the perspective of the constituents of the home department. I think

John Kenney has done a fantastic job describing the third angle so I will refer you to his writing on the subject. This post will focus on the former two angles.

As you may know from my previous posts, my partner is a counseling therapist. The other day, while I was writing the previous posts, we were discussing transformative journeys (such as meditation and yoga retreats). I likened this to participating in labs or accelerator programs. I mentioned the importance of Aftercare with programs like this and how I frame the participant experience using Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, which touches on the need to create the conditions for a home department to put into practice what the participant learns.

She then shared that one area she wants to incorporate into her practice is helping people integrate transformative experiences. “Integration!” I exclaimed. This is a far better word than implementation or even adoption. How does the organization integrate lessons for transformation? Furthermore, how does the participant integrate a transformative experience?

We started searching online for “transformation and integration,” which led us to this phenomenal piece by Susan L. Ross: The Integration of Transformation: Extending Campbell’s Monomyth. I think my brain is still on fire from reading this, so let’s see if yours will also light up.

The Journey Outward

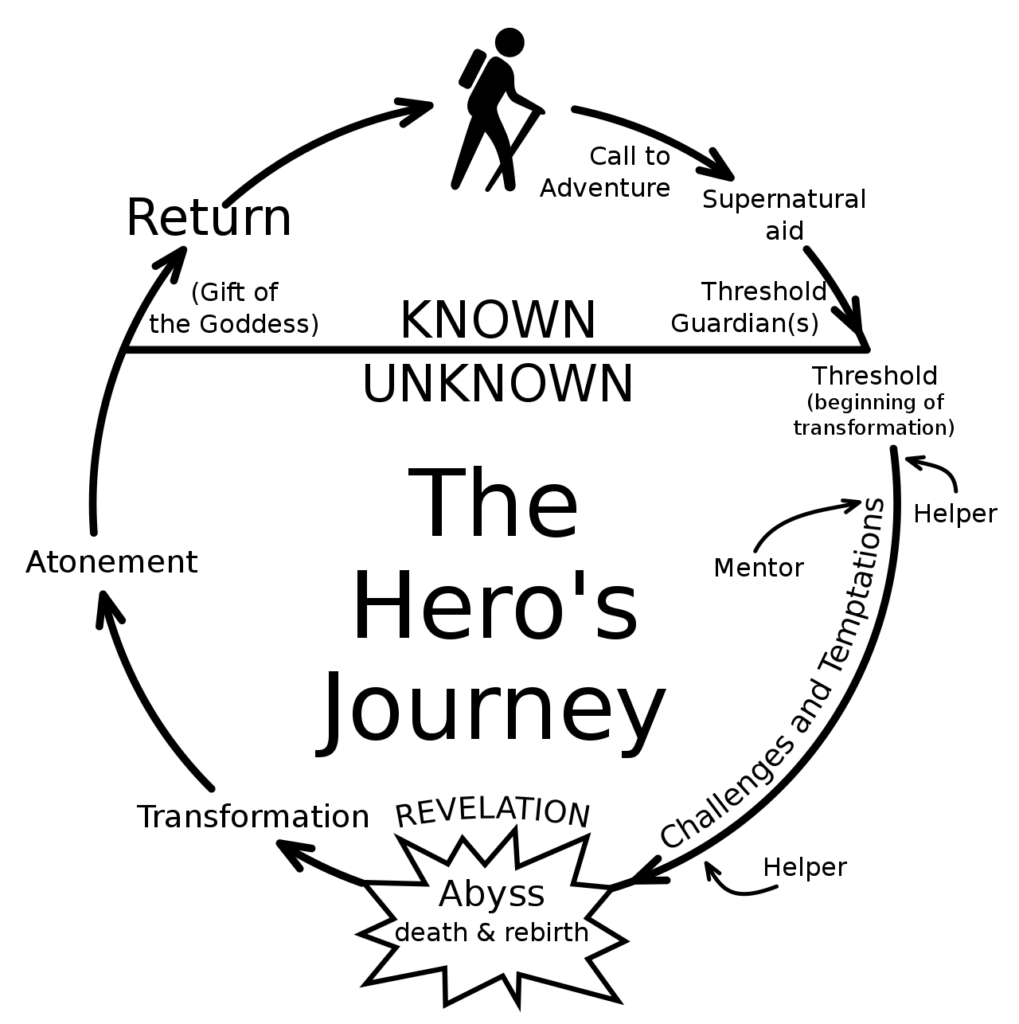

Even at its most basic interpretation, the Hero’s Journey is one I have found useful in framing the design of programs to support individual and organizational transformation. Ross describes the journey this way:

Traditional communities have guided individuals in transformation processes of initiation in order for the individuals and the collective to flourish. Initiates face growth-producing challenges and learning, which in aggregate, cause the person to metamorphose from one identity and social status to another through departure, initiation, and return processes. (Ross)

Mythologist and historian Joseph Campbell distilled the framework of human transformation by analyzing hero myths across cultures and periods, now known as “the Hero’s Journey”.

The journey metaphor illustrates how an ordinary individual can transform to become a hero, a greater, more complete, and capable self.

Many of us have an aversion to the term “hero”. Ross helped me unpack my baggage with the word when she wrote:

The ultimate goal of transformation is not heroism or even finding one’s self and is most pointedly, an endeavor towards wholeness. Transformation creates wholeness through open receptivity, unyielding personal growth, chaos, and the integration of opposites, ego, and the treasure received. The catalytic experience yields the opportunity to receive the treasure, the individual’s commitment to growth drives the entire process, chaos facilitates the dissolution of self-structures and, integration reorganizes structures of the self that reflect the knowledge, love, and power endemic of the boon. The self and boon are indistinguishably one.

Anyone can be a hero, and heroism is not about a paternalistic approach to “saving others.” It is having the courage to face your ego, venturing into the unknown, being open to growth and, as Ana Jain tweeted, “not retreating from the ache.”

In his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell describes the transformative journey as:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are then encountered, and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

An “initiate” (participant) leaves the known world (e.g. their home department/organization), ventures into the unknown world (e.g. the supernatural wonder of an innovation lab) and returns with new abilities and an opportunity to share the gains of their adventure with their peers (e.g. colleagues). Ross states, “the boon is in essence, the initiate’s unutilized potential to become established, substantiated, and realized.” The process of transformation is the process of self-actualization:

The words “living in the world” connote a functioning participant in society, and I argue, a person who possesses a state of being in which her strengths are actualized and used. In other words, she “must integrate it [the boon/self] in a rational life” (2004, p. 119) and live in the world as that integrated self, in possession of her potential such that the self is reified.

Campbell’s Model

The hero’s journey consists of:

- A call to adventure

- Crossing the threshold from the known into the unknown

- Facilitators (helpers and mentors)

- Challenges and Revelations

- Return

Labs (or other containers) design the “special world,” guide “initiates” along their journey, and do what we can to facilitate (to ease) the transformative experience. My conversation with my partner got me thinking differently and more deeply about what aftercare looks like in the context of organizational transformation, which led us to Susan L. Ross’ incredible expansion of The Hero’s Journey.

An implicit assumption that many of us lay observers would make about Campbell’s model is that the journey ends at the “return.” However, Ross rightfully points out that “the journey is not actually completed until the initiate integrates the transformative experiences earned along the way”

So how does an initiate integrate a life-changing adventure?

From mythological adventure to practical deed

Central to the hero’s journey is the task of finding and bringing back “something that the world lacks” (Campbell, 2004, p. 120). Integrating the gift into daily life is necessary because “this is the world in which the heroes will have to function; having accomplished their mythological deed, they now come down to do the actual, practical one”

Citing Campbell’s lecture, Ross outlines three post-journey scenarios for the initiate:

The first path of integration transpires if the initiate rejects society and returns into the bliss because “no one cares about this great treasure you have brought . . . there is no reception at all, you go back into your own newly unified whole and let the world go stink”

In the second circumstance to integrate, the initiate distorts the boon (i.e., the self) “in terms of the society, so you’re not giving them a goddamn thing; they’re only getting what they want”.

A third option of integrating involves “trying to find a means or a vocabulary or something that will enable you to deliver” the boon in a way that society is able to receive….some little portion of what you have to give”.

Following a transformative experience, three things can happen in an organizational context:

- The initiative and the new value they bring are rejected, and they evade integration with their organization. This might look like resigning or transferring to a new department (an evasion of the status quo)

- Either assuming the value will not be understood or having been rejected in some way, the initiate withholds the gifts and conforms to what is expected of them (a return to the status quo)

- The initiate finds a way to prepare the receptor, communicate the value and share the benefit in a way that can be received and understood, at least in part, by their colleagues (the carrying out of transformation)

Achieving true integration requires a great deal of introspection and a humble and empathetic approach:

The returnee responds to an inner call−−a need−−and, upon return, must adopt a “pedagogical attitude of helping [others] to realize the [same] need (2004, p. 121). Campbell warns, “this requires a good deal of compassion and patience” (p. 120) directed towards others and one’s self. The returned “hero” must first thoroughly understand the treasure−−what it is that she discovered and learned during her adventure, which is, in and of itself, a major accomplishment. She must also accurately gauge a societal need that the boon meets and, finally, learn how to deliver the information “in terms, and in proportions, that are proper to their ability to receive” (p. 121) −−in a way that others can understand.

“Bringing the boon back can be even more difficult than going down into your own depths in the first place” (Campbell quoted in Ross).

Going on the adventure and being open to change for yourself might be easier than returning as a changed person. This could also be a source of hesitation on the part of potential participants in these kinds of programs: “What will my colleagues think of this?” and reveals a necessary new layer of empathy for participants.

The ability to integrate the transformative experience into your home organization upon return (the practical deed) requires one to first integrate the experience within themselves.

Integrating a transformative experience

Ross conducted some compelling primary research to understand better the process of integrating a transformative experience. She found “that integrating a transformative experience involves a shift in identity by letting go of the outdated self in order for the new or transformed self to emerge.” To be successful in the external processes of integrating transformation upon return, one must first be successful in the internal processes of integration.

The success of an intervention depends on the interior condition of the intervener. -Bill O’Brien

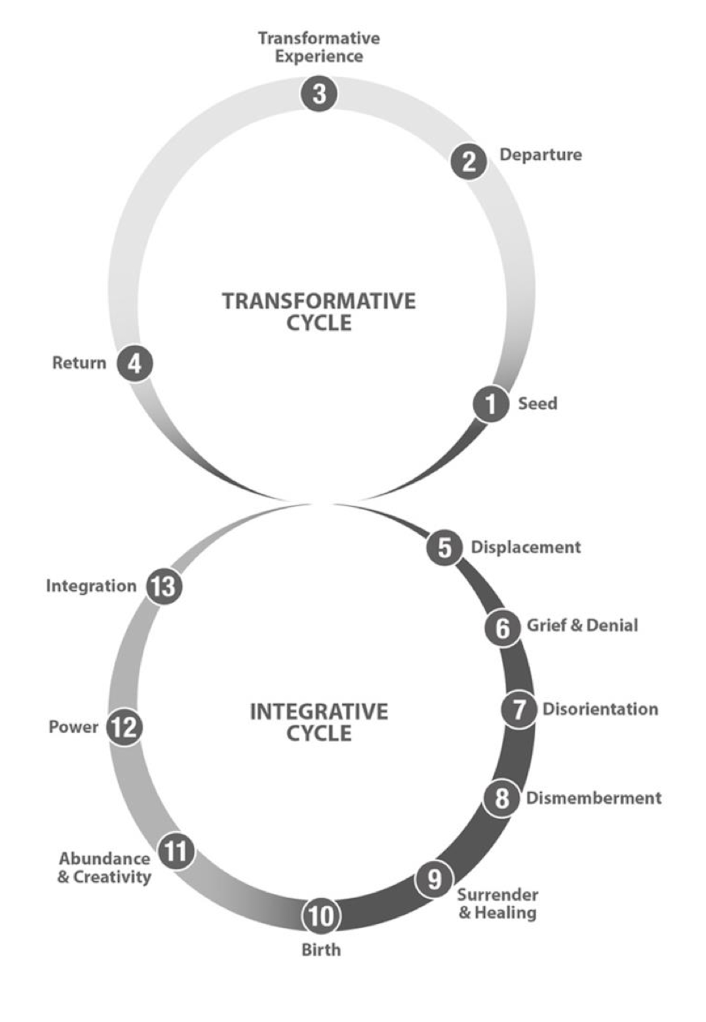

To address this missing element of the transformation process, Ross has developed a helpful integrative cycle consisting of 9 phases following the return:

- Displacement

- Grief & Denial

- Disorientation

- Dismemberment

- Surrender & Healing

- Birth

- Abundance & Creativity

- Power

- Integration

Knowing these phases can help a person better integrate (understand, make sense of) a transformative and innately unfamiliar experience. Because integration is a prerequisite for the participant to be able to coherently and effectively communicate the experience and its value to others, it is something that designers and facilitators must consider and maybe help “initiates” avoid a “Plato’s Cave” situation.

The dismemberment (8) and surrender & healing phases (9) sound similar to the metamorphosis of a caterpillar into a butterfly; transformation requires us to turn to goo:

cause the individual to break down and lose a sense of control over her life, and dissolution of the outdated identity. Emotions become consuming (i.e., shadows or the underworld), and the initiate experiences a sense of turning psychospiritually inwards, which provokes a resounding need for quiet and physical stillness.

This excerpt aligns nicely with the concept of unlearning for innovation. Additional links can be made to ideas in Theory U “let go in order to let come” (“dissolution of the outdated identity”) and retreat & reflect: “a resounding need for quiet and physical stillness.”

Ross continues to explain that novel outcomes result in new ways of understanding and relating to the world and self that requires integration:

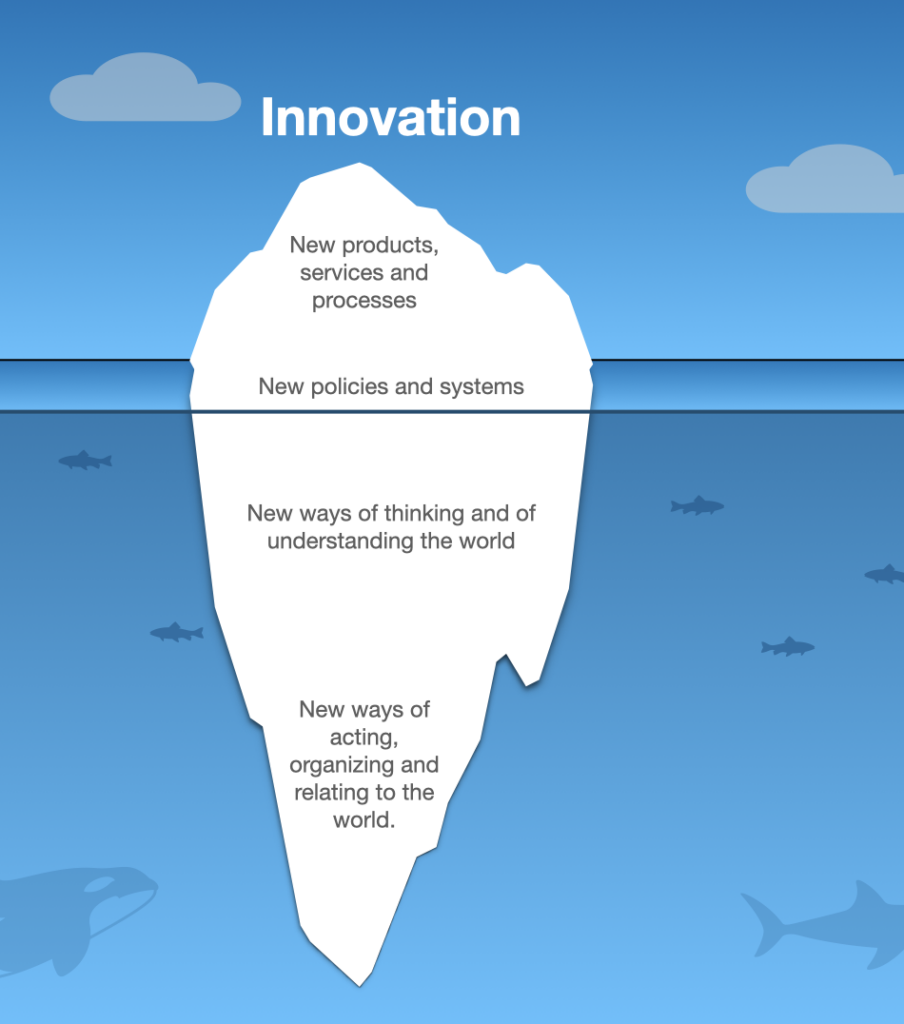

Outcomes indicate that novel circumstances occurring during the life-changing experience (i.e., the hero’s journey) require that the individual integrates new ways of thinking, behaving, perceiving, and experiencing the self, which coincides with transformative learning theory.

This excerpt harkens back to the OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation’s definition of innovation as “new ways of thinking and understanding the world” and “new ways of acting, organizing and relating to the world.”

A participant in Ross’ research reflects on the experience of a transformative journey:

The transformation cycle] pushes you through your comfort zone, shows you what you’re capable of and the strength you have inside of you. It gives you the ability to transfer it on to other things in your life, whether it be bad relationships or moving from the place you’ve lived your whole life. It will bring a whole different energy into your existence and consciousness.

With minor ad-libbing, this quote could easily be a testimonial from a participant in an innovation lab or accelerator program.

From doing to being

In summary, the Hero’s journey is a useful metaphor when designing programs for organizational (and professional) transformation as it helps us frame the experience of venturing into novel, unfamiliar, and uncomfortable territory and practices, which bestow some things onto the participant that are needed in their organization and the world.

the integrative cycle is predominantly about “being,” while the transformative one is about “doing,”

Coupled with Ross’ integrative cycle, we can better understand the internal integrative processes of participants (being), thus opening the door to facilitate the absorption of a transformative experience. In doing so, facilitators of transformation can increase the likelihood of integration upon return, thus putting the transformation into effect (doing).

Prevailing thought suggests that transformation involves a life-changing process that ends upon return rendering the individual fundamentally and permanently changed and endowed with a bounty from the journey. The Figure-8 pattern indicates that in addition to a life-changing passage, transformation requires a complementary inward quest that produces integration of the treasure, ego, and internal polarities. The two interrelated cycles, linked together through one’s readiness to transform and willingness to go into the inner darkness, render a complete and balanced process.

The infinity-shaped Figure- 8 pattern depicts the full acquisition (receiving the treasure) and realization (integration) of transformation that directly addresses the existential angst behind feminist critique that the monomyth and similar accounts “do not adequately describe women’s experience”

The balance of feminine-masculine, internal-external, and being-doing that the Figure-8 pattern represents provides much-needed inspiration and guidance to designers and facilitators working to transform our organizations. It adds a new dimension of empathy for participants venturing into the “unknown world” of accelerators and labs, as well as insight into ways we might ease both external and internal processes.

As facilitators, we do not have the treasures. Those are for our participants to realize. We are guides facilitating the journey outward, and perhaps we need also to find ways to facilitate the journey inward.

Transform yourself to transform the world

— Grace Lee Boggs