Manipulation is deceptive. Design should be supportive. Theoretically, the two are separated by intention. But increasingly, in practice, the two forces are converging.

This may be inevitable, as fields of sales, marketing, and design collide. I hope not. I’m troubled by the collision, and how it manifests in digital products.

In many ways, the collision is most obvious in startup culture—a culture that demands viral “hockey-stick” style growth over actual and meaningful impact. Get bigger. Acquire users. Scale, scale, scale. Don’t worry about monetization or impact; just get a massive user base.

In 1971, Victor Papanek said:

There are professions more harmful than industrial design, but only a very few of them. And possibly only one profession is phonier. Advertising design, in persuading people to buy things they do not need, with money they do not have, in order to impress others who do not care, is probably the phoniest field in existence today.”

I wonder what Papanek’s thoughts would have been on venture-backed startups, “growth hacking,” and user experience design. I offer here two recent examples, two articulations of manipulation wielded by design. My intent is to spark a discussion concerning ethics in design. Please, let me know your thoughts.

The Full Empty Classroom

I have a course listed on the popular online learning platform Udemy, and 446 students enrolled within two weeks. It has a five star rating. The course is listed at $49. That’s $20k in two weeks, and if I can keep this up, I’ll be rich.

Before I go on, I must admit a personal backstory of skepticism. I decided to try Udemy (and several other online learning platforms) in order to test my long-standing assumption that online learning is ineffective for teaching and learning theory. When confronted with complex discourse and complicated topics in a MOOC or online environment, I don’t think most students learn very much. I don’t think teachers teach very much, either, as most online platforms are just video delivery services. I don’t think investors in these systems will actually earn very much, and I don’t think institutions that partner with the systems realize the expected benefits. We’re in an ed-tech bubble, but this one seems to have lasted as long as computers have been affordable: we’ve played this game before with LMS, and computers in the classroom, and iPads in K-12.

But it’s been years since I personally participated in an online class, as either a professor or a student, and so I was challenging myself to validate my assumptions in a more rigorous manner. Maybe the emperor of Kingdom MOOC really is wearing clothes. And so I signed up to teach a Udemy course, filmed one of my lectures—a lecture that is extraordinarily well received when delivered in person—and followed the Udemy setup instructions.

Udemy recommends that you have your friends review the course:

Invite Family & Friends to review your course: E-mail 10 of your closest friends and family and ask them to write an HONEST review of your course. Create a coupon (instructions here) to give them free access. Having a few reviews will help you get more students enrolled in your courses.

That seems sketchy, but only a little, because after all, what are friends for? I recruited 10 friends to examine the course. They all gave my five star reviews and had some very nice things to say.

Fundamentally, it’s about taking responsibility for the things we unleash in the world.

And then I read this article, about how Bogdan Milanovich got 500 students in his class, and this article, about how Justin Mitchel got 1400 students in his class. The “technique” is simple: create a free coupon code, and publicize all hell out of it. Get it on slickdeals. Put it on reddit. (Udemy offers this helpful tip: “You will probably have at least one commenter accuse you of violating Reddit terms or soliciting. This is to be expected; Redditers are very protective of maintaining harmony in the community. They may also flag your post as inappropriate.”) Udemy urges instructors to follow in the footsteps of Milanovich and Mitchel. Grow your userbase with free students, and when the masses experience your awesome teaching, you’ll end up with hundreds of five-star reviews.

So I did it. I posted it to reddit, and it was spotted by a couponing site, and suddenly, my class was full.

And then I waited, to see what people would think about the content. Would they ask questions? Would they engage? Would they review the course?

My “students” didn’t do any of those things, because they weren’t actually students. They were couponers. They signed up for the course because it was free, not because they wanted to take it. And they didn’t actually watch any of the content. 428 of the people that signed up haven’t watched even a minute of the hour-long course. They gained nothing, except a minor dopamine kick from getting perceived value for free.

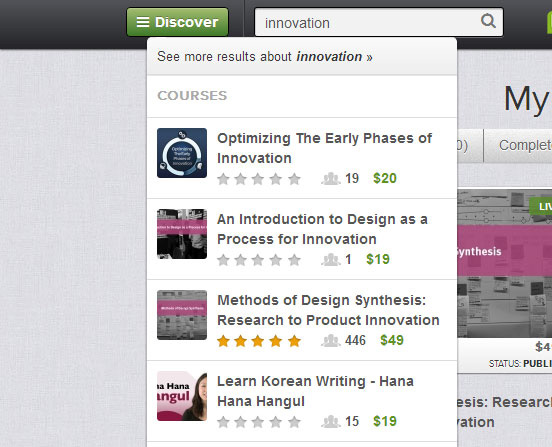

But Udemy gained two things: They gained massive growth, which will make their investors (who put 16M into the company) very happy when they try to unload. And more importantly, they gained my tacit participation in a game of manipulation. Because this is what it looks like to people who now search for the word “innovation” on Udemy:

That appears like a full, extraordinarily positive, extraordinarily successful course. The grouping of the five-star rating and the number of people in the class makes it appear as if those things are related. The sheer number of people in the class looks like a validation that online learning works, that Udemy is a successful educational platform, and that instructors can make it rich bringing their course work online. That tiny piece of design almost serves as the validation of disruption of the entire education industry: we don’t need classrooms, colleges, administrators, overhead, or anything else about traditional higher education, because this online stuff works.

Viral Growth Strategy

My friend Brian just took a job at a successful company. He moved from Austin to SF, and last time I talked to him, he was having a great time. So I was surprised when I received an email from him that looked like this:

From: Brian

Subject: Quick Favor

I’m starting my next entrepreneurial project and looking for the right people to do it with. So, I’m applying to join FounderDating – a handpicked network of entrepreneurs. As part of the application process, I need people to vouch (aka act as a reference) for me. I’m hoping you can do this for me as they won’t look at applications without it.

It’s quick, just click this link: https://members.founderdating.com/

This is a really important part of the process, so thanks for your help,

Brian

I emailed him to see what was up. He told me that he was happily employed and wasn’t starting a new entrepreneurial project. He had no idea that FounderDating was sending that email to his friends.

Perhaps it’s just a coincidence, but I got a request on LinkedIn the same day from someone I hadn’t spoken with in years, Christine. It looked like this:

From: Christine

Subject: Vouching for you…

I was asked to vouch for a few people to join FounderDating – an invite-only network of entrepreneurs (50% engineers) all ready to start their next side-project or company. You’re on my short list. I highly recommend applying.

Apply here > https://members.founderdating.com/application/?frvch=18531 (Note: copy and paste this link if it’s not clickable).

Check it out,

I emailed her. She had no idea that it was sending LinkedIn requests to people.

Turns out I’m not the only one receiving these requests, or puzzled by them. Here’s a thread on hackernews referencing these same emails. The debate is interesting, and so is this comment by the founder of FounderDating:

We not only state (in white writing) on black backgroud) that “a message will be sent to your chosen linkedin contact) and let you see the message but it’s also completely opt-in – no tricks where you can’t find the “x”. People can choose to a) not send or choose who they send a message to. There is nothing sneaky about it. If someone doesn’t read the line “this will send a message” there isn’t much we can do about that.

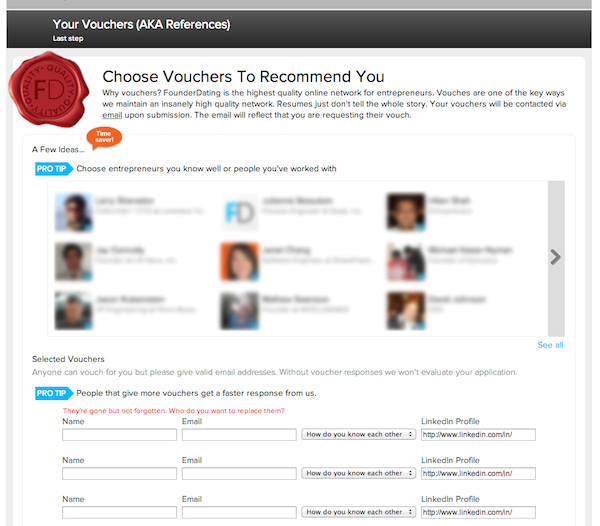

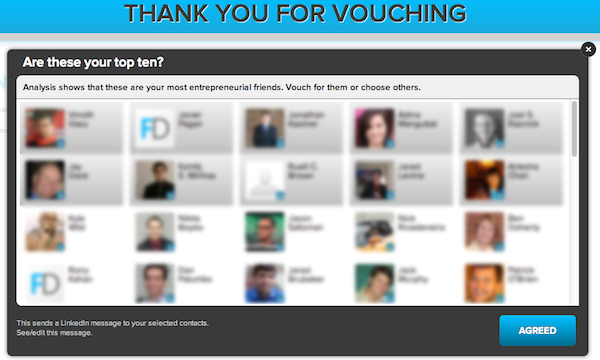

Here’s a screenshot of how the no-tricks, non-sneaky designs looks in action:

These screens were created, on purpose, to manipulate people into sending mail to their connections without fully realizing what they were doing. The wording of the emails was selected, on purpose, to manipulate these connections to sign up for a service without fully realizing what they were doing. The designer is counting on people to read quickly, to avoid thinking critically, and to trust. Both Brian and Christine trusted, and when they did, the designer leveraged Brian and Christine’s personal relationship with me in a way they weren’t expecting. If the output was to empty my bank account, this would be called spear phishing. Here, it’s called a “viral growth strategy.”

Reflection

Most design is manipulative. Physical affordances manipulate people to hold or push or pull things. The urgency of alerts manipulates us to take action. Colors shift our mood or direct our attention. This is interaction design 101, applying basic principles of cognitive psychology to our work in order to leverage mapping, visibility, physical and logical constraints, labels, and feedback. Interaction design is largely about removing cognitive friction or producing a happy path—in order to manipulate someone into realizing a goal. That type of manipulation is typically called “helping,” and it is often, actually, helpful.

Pelle Ehn describes this as, ideally, an emancipatory practice—one that identifies with oppressed groups and supports their transcendence in action and reflection. It would be a stretch to describe online learners or startup founders as oppressed, yet the larger point is that of design as rooted in a historical context of empowerment.

Participatory design places a heavy check on manipulation by including the people who will use or live with the design in the process of its creation. An empathetic approach means feeling what someone else must feel, truly finding a way to live their pain or wants or needs or desires, and many designers embrace this approach. Design frequently serves people who otherwise cannot serve themselves. But if that’s true, then there exists a dynamic of disproportionate power influence. Design is biased and cannot be apolitical.

I fear there are practitioners who are competent or even extraordinary craftsman, but have learned no real ethic, no guiding set of axioms in which to ground their work. I don’t mean that designers are lacking morals, or are even bad people. I mean that many practitioners seem to have no consistent set of values that they automatically fall to when doing their jobs.

Chris Nodder has written an excellent book about this called Evil by Design. His book is organized around the 7 deadly sins, as if to imply some cardinal vice designers can’t help but avoid. Yet other disciplines with extreme scaled-influence or disproportionate power influence are required to understand the ethical ramifications of their work. Engineers learn ethics during their undergraduate studies. All doctors study medical ethics. I learned only a little about the ethics of design during my formal design education, and I didn’t really understand the little that I learned. I certainly didn’t respect it as a legitimate course of study, because I had the design hammer, and the world was full of nails. I intended to do good, and so of course it was good that I would do.

I now try to respect a consistent design ethic. It makes design harder. It also makes it more meaningful. I feel that our industry needs a massive check on the broad power we hold and the manipulation that comes with it. It is not enough to intend to do good. It is not enough to simply intend for people to learn online or intend for people to find partners to run their startups. That intent must be qualified, and the qualification happens at a micro, detailed, tiny level of design specificity.

It happens not with a broad stroke (“I think about people when I design”) but in every detailed product decision, comparing each decision to a set of values. It’s about asking questions like “does the way this is presented get people to do something that helps them, or helps me?” It’s about avoiding decisions that purposefully prey on human nature—a human nature to be intellectually lazy, or to scan instead of reading, or to consider things that are positioned next to each other as related, or to avoid reading the terms of service, or to mislead and misdirect.

Fundamentally, it’s about taking responsibility for the things we unleash in the world.

Image of potter’s hands courtesy Shutterstock.