Save

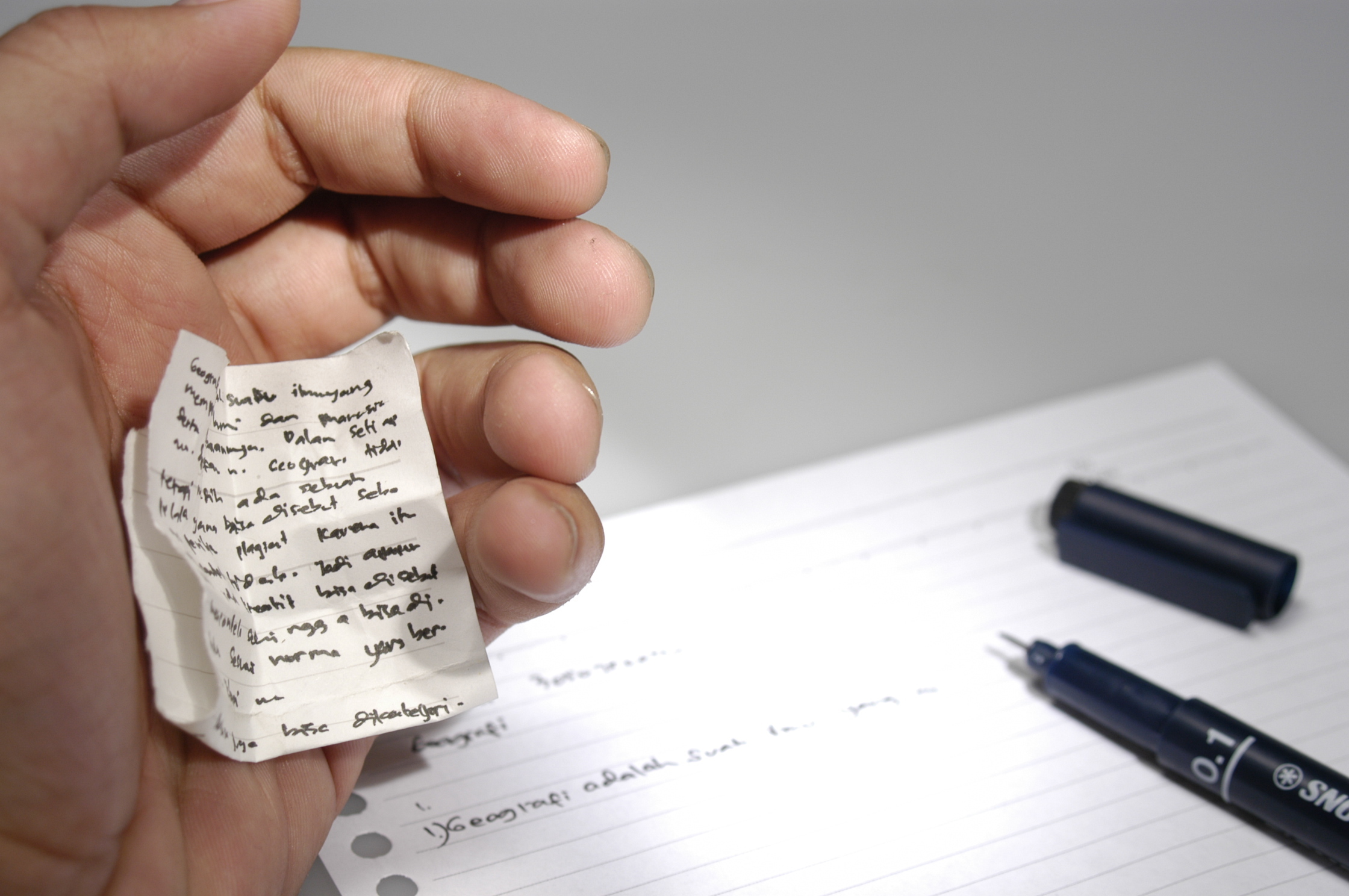

Much of the academic world is deeply worried about whether AI is leading to more cheating, although academic dishonesty, which covers a broader range of practices, might be a more accurate way of describing the problem. Either way, academic institutions’ tendency to impose rigid rules may well end up sanctioning some students unfairly.

The president of the academic institution where I have been working for thirty-five years, Santiago Íñiguez, has recently written about the subject on LinkedIn, taking an interesting approach, albeit one that in my opinion doesn’t fully get to the root of the problem. From my experience, I think it is essential to see academic dishonesty in terms of the institution rather than the students because in many ways, students’ behavior reflects the way we measure learning.

This is not a new problem: trying to measure a student’s performance through a grade, no matter how average it may be, is reductionism. We live in a world in which eleven-axis multidimensional graphs are used to evaluate a soccer player’s performance, but students simply get a grade point average that not only provides little or no relevant information but often distorts reality. Laszlo Bock was senior VP of People Operations at Google and concluded that there is no correlation between a person’s average grade and their professional ability. Centuries of development of educational methodologies have helped us to end up focusing on the variable that tells us nothing about someone’s abilities.

The root of the problem lies in what is known as Goodhart’s Law: “When a metric becomes a goal, it ceases to be a good metric.” If institutions and society make a student’s average grade the be-all and end-all, then instead of maximizing their learning, students will make their objective maximizing their average grade, and academic dishonesty is the best way to achieve that goal.

The focus therefore should not be on how to reduce academic dishonesty, but on creating a system that assesses students less simplistically, that properly assesses their potential. As Einstein said, if you judge a fish on its ability to climb a tree, it will believe it is stupid.

Punishing students for using AI runs the risk of destroying their chances of being accepted into a top-tier institution. Sure, there are rules, but do those rules make sense? Why simply prohibit the use of AI? Are we talking about dull students who try to cheat the system or very bright ones who simply question the rules? Is it worth clinging to “the rules are the rules” in such a case? It should be clear by now that traditional rule systems no longer work: to deal with the current scenario, we need a drastic overhaul of the ethics that govern education.

Institutions that prohibit the use of AI are depriving their students of the competitive advantage of knowing how to use the technology properly. Instead, they need to assess students on how well they have used AI; if they have simply copied and pasted, without checking, then they deserve a low grade. But if they can show that they have maximized their performance and can verify the results properly, then punishing them is no different from doing the same for using Google or going to a library. Let’s face it, cheaters are always going to cheat, and there are a number of ways of doing so already.

The long and short of it is that students are going to use generative algorithms, and if a single grade depends on it, in which their future is at stake, even more so. And as with all new technology, they’re going to misuse them, ask simplistic questions, and copy and paste, unless we train them on how to use it properly. The objective is to use technology to maximize the possibilities of learning, which is a perfectly compatible objective if it is well-planned. Or should we go back to using pencil and paper to prevent students from using AI?

In fact, I am completely sure that for the vast majority of so-called hard skills, students will increasingly use AI assistants that have adapted to their learning style. AI isn’t going to destroy education, but to change it. And that’s a good thing because we’re still largely teaching in the same way we did back in the 19th century. AI is the future of education, and no, it’s not necessarily dishonest.

The moment has come to rethink many things in education, and failure to do so may mean the loss of a great opportunity to reform an outdated system that, moreover, has long since ceased to deliver the results we need.

The article originally appeared on Enrique Dans (Spanish).

Featured image courtesy: Hariadhi.

Enrique Dans

Enrique Dans (La Coruña - Spain, 1965) is Professor of Innovation at IE University since 1990. He holds a Ph.D. (Anderson School, UCLA), a MBA (IE University) and a B.Sc. (Universidade de Santiago de Compostela). He writes daily about technology and innovation in Spanish on enriquedans.com since 2003, and in English on Medium. He has published three books, Todo va a cambiar (2010), Living in the Future (2019), and Todo vuelve a cambiar (2022). Since 2024, he is also hacking education as Director of Innovation at Turing Dream.

- The article challenges the view that cheating is solely a student issue, suggesting assessment reform to address deeper causes of dishonesty.

- It advocates for evaluating AI use in education instead of banning it, encouraging responsible use to boost learning.

- The piece critiques GPA as a limiting metric, proposing more meaningful ways to assess student capabilities.

- The article calls for updated ethics that reward effective AI use instead of punishing adaptation.

- It envisions AI as a transformative tool to modernize and enhance learning practices.