Web companies hate losing customers. The cost to acquire new customers is high, and engaged users are the revenue-generating lifeblood we all desperately need to keep going.

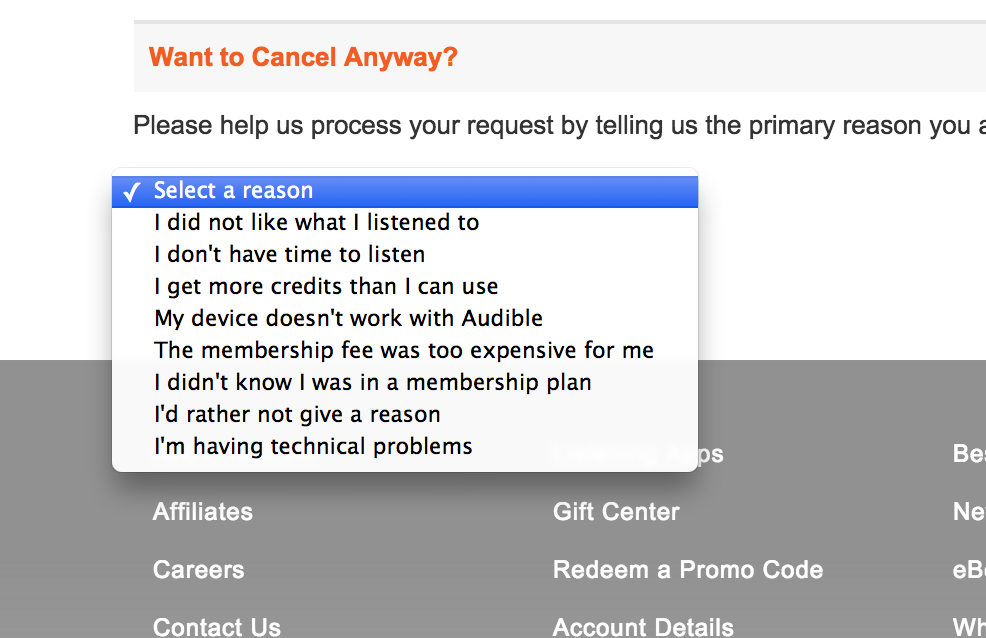

We spend a lot of effort creating new content and building new features to bring value to current users and entice them to stay. When users do leave, the prevailing wisdom is that something must have been wrong with the product. We build cancel questionnaires around this assumption, with options that are largely product-centric.

Assuming every problem is product-related drives a product-centric approach to fixing them. But what if problems are more complex than simple fixes to content or features?

An engineer I used to work with once said — and this is incredibly insightful advice for product managers — “People are complicated.”

I work for a video-streaming service with a monthly subscription model (similar to Netflix). A few months ago we ran a survey with a group of users who’d cancelled the service. We asked about satisfaction across three product areas: usability, content (videos), and access (can you access the service on your preferred devices). The results were surprising. Even users who’d canceled the service rated their satisfaction high in all three areas. And their overall satisfaction with the service was rated just as high. Needless to say, we were perplexed. Why would someone cancel a service with which they were highly satisfied?

It wasn’t until a few weeks later, as I was reading Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, that the answer became clear.

What makes someone satisfied?

Kahneman, a psychologist and Nobel Laureate in economics, dedicates a significant portion of his book to examining the psychological underpinnings of how people make decisions. The part that struck me specifically was his discussion of the way an object’s utility impacts our desire to have it — and, ultimately, how it impacts our satisfaction.

The utility of an object is defined as its perceived ability to satisfy a need or desire. The more utility a person perceives something to have, the more satisfying it is for them. Kahneman explains this from an economic perspective:

A gift of 10 [dollars] has the same utility to someone who already has 100 [dollars] as a gift of 20 [dollars] to someone whose current wealth is 200 [dollars]. We normally speak of changes of income in terms of percentages, as when we say “she got a 30% raise.” The idea is that a 30% raise may evoke a fairly similar psychological response for the rich and for the poor, which an increase of $100 will not do.

To extrapolate, a gift of $10 has less utility (and satisfaction) to a person who already has $200 than it does to someone who only has $100. The basic concept is that everyone who is considering purchasing a product weighs its perceived utility against its cost. If the utility seems high enough to justify the cost, the consumer is more likely to buy.

So, a customer comes to your service. They weigh utility vs. price, choose to purchase it, and are satisfied with the experience. Why would they still decide to cancel?

This is where things get interesting. The original idea, put forth by Daniel Bernoulli in 1738, emphasizing the role of utility in decision making is actually flawed. It assumes that it is the inherent utility of an object that makes a person more or less satisfied — that if you and I both have $100 we will be equally satisfied based on the inherent value of $100. As Kanheman shows, this assumption is wrong:

Today Jack and Jill each have a wealth of 5 million.

Yesterday, Jack had 1 million and Jill had 9 million.

Are they equally happy? (Do they have the same utility?)

It is pretty clear that Jack would be stoked and Jill would be reeling — even though they both have $5 million, which should have the same inherent utility. As Kanheman puts it:

The happiness that Jack and Jill experience is [actually] determined by the recent change in their wealth, relative to the different states of wealth that define their reference points (1 million for Jack, 9 million for Jill).

This was my aha moment.

Satisfied people aren’t canceling because the inherent value of the product has changed. What has changed is the utility they perceive in that moment, based on their current life state.

As part of our cancellation process, the organization I work for has a simple questionnaire. One of the options customers can click to tell us why they cancelled is “other,” with an open text field. As I went back through the responses, I noticed some consistencies:

Traveling for the summer will be back.

Got laid off, but will be back when I find a job.

Have a pile of books I need to read.

These “other” responses had previously slipped under the radar, but now they were coming through loud and clear. Hoping to retain customers by keeping them on a path of continual engagement blatantly ignores the fact that people have lives beyond your product.

Our current approach to customer retention — improving the product itself — assumes that the inherent value of the product is what satisfies. We’re making the same mistake Bernoulli did over 200 years ago. What we’ve found is that, often, people are satisfied with the product but changes in their life situation have temporarily decreased its perceived utility. That decrease shifts the utility vs. cost equation in their minds.

Not all cancels are created equal

Don’t get me wrong, product improvements do help the overall experience. They’re an important piece of the puzzle, but they’re not the silver bullet for increasing customer retention.

We must redefine “retained customer.”

Loyalty does not mean a customer must stay with you indefinitely. If a user cancels in order to travel, then comes back to the service a month, or two, or three later, did you really ever lose them? A cancel is only a cancel if they don’t intend to come back.

The goal of any business is to create a great experience, and to support the needs of its customers. What if we embraced and respected the fact that people have lives outside of our products? What if we designed for the fact that the utility we deliver will ebb and flow with the changes in their life situation? How would we structure our products to support that?

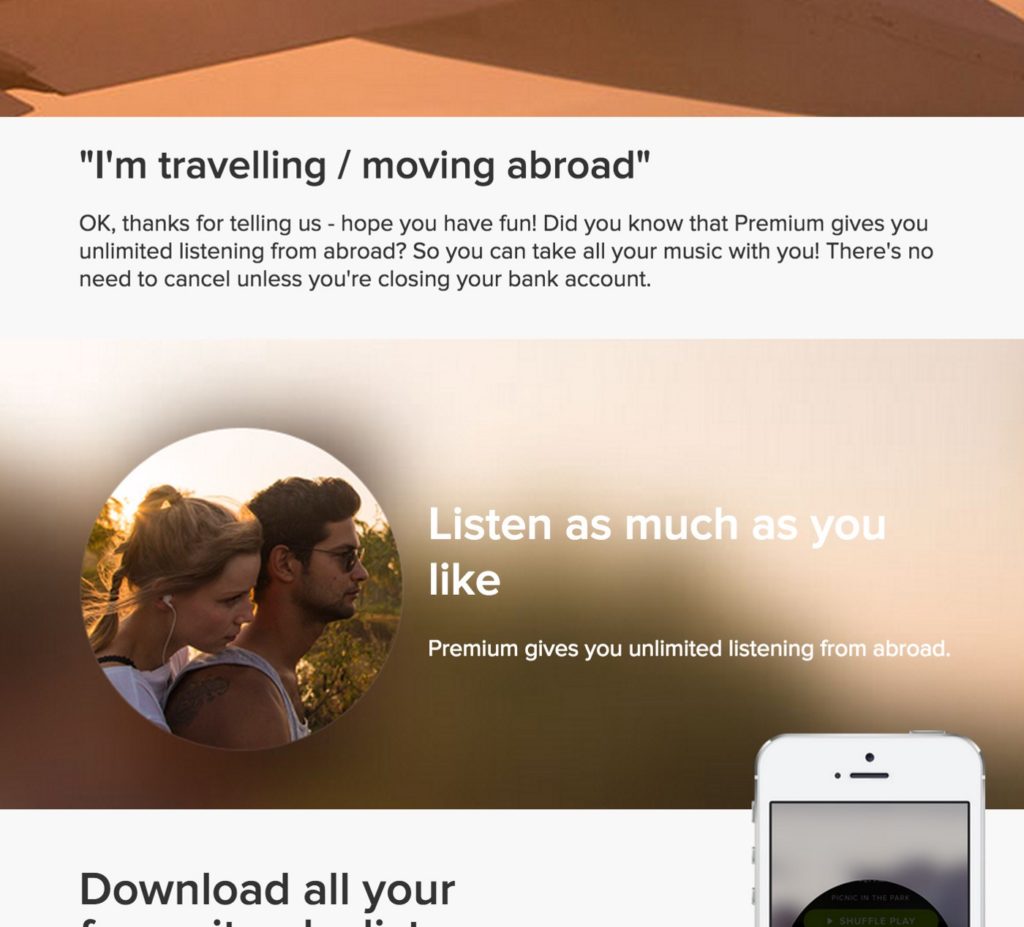

Spotify starts down this road with their cancellation process. They include an option to say you’re traveling and then, before you make the final decision to cancel, they deliver a nice explanation of how they can support your trip. Here’s what it looks like:

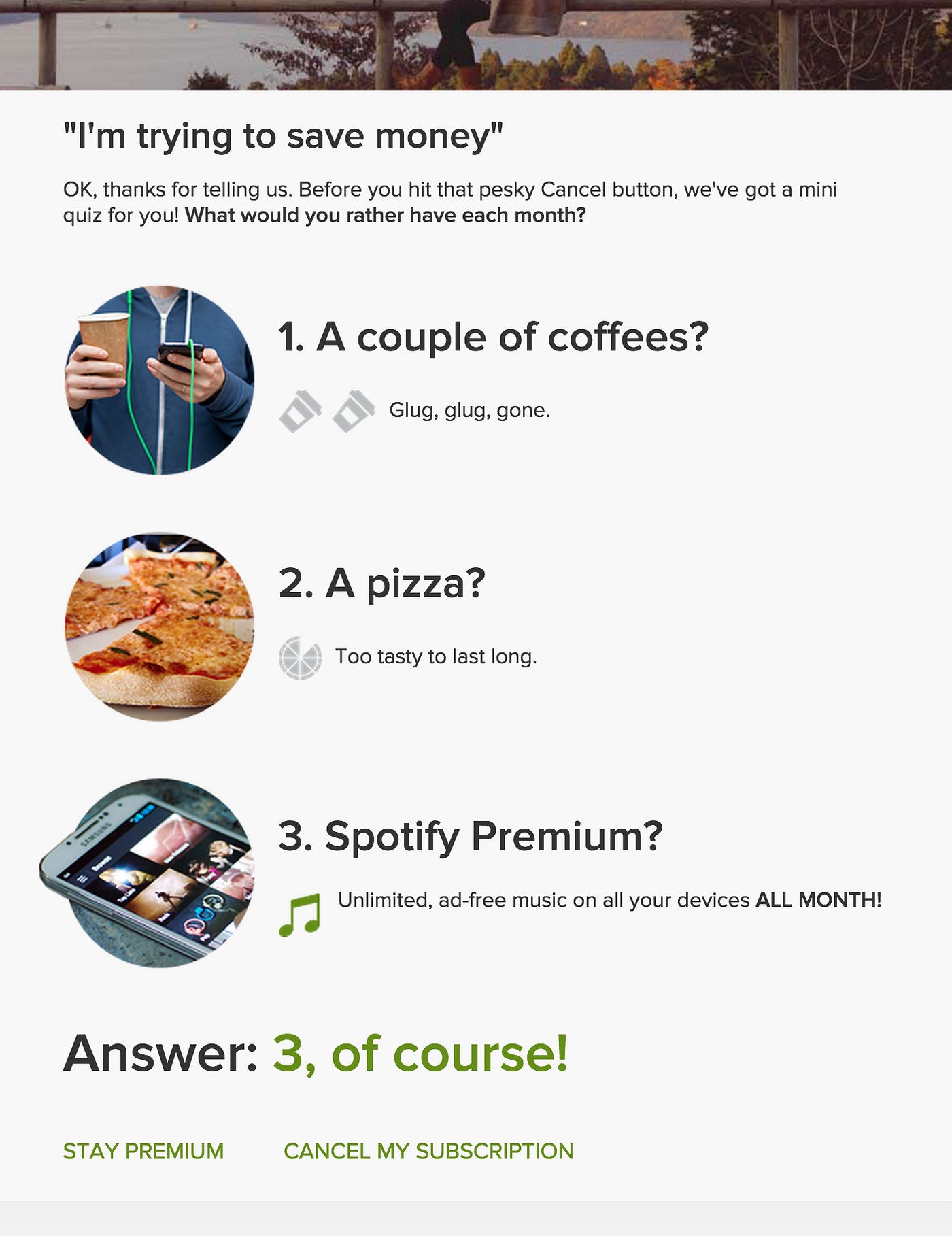

However, Spotify’s approach to the user’s response that “I’m trying to save money” tries to convince the user that Spotify is the best use of his or her money, which I’d argue doesn’t respect a user’s need to manage his or her current life situation.

Think: User-centered retention

Take time to identify the kinds of external events that may temporarily impact the utility of your product. Then, develop retention strategies around those events.

Is your product impacted by nice summer weather, when people want to spend more time outside? Instead of fighting it by convincing them to come inside, develop features that help your users take advantage of the weather — or features that encourage them to take your product along. Or, accept that summer may be a low point and focus hard on having great content and features ready when temperatures drop. TV networks get it. Summer is a time for reruns.

If you have a cancel questionnaire, structure it to be as user-centric as it is product-centric. Give your users the option to tell you why they’re leaving instead of pushing them down a specific path. You might learn something.

Don’t assume everyone who leaves is a dissatisfied customer. Sometimes, life happens. If you make it hard for people to quit when they need to, or pester them to come back before they’re ready, you run the risk of frustrating someone who would’ve otherwise returned on their own.

Instead, respect that your users need to manage their own lives. Understand that your product is only a part of their lives, and you’ll be rewarded with loyal customers who return again and again.