Save

We are brought up to be honest. Lying is seen as a bad thing to do. Yet, often, in real life, deception is used to make life better for someone, not worse.

Parents can buy a lavender-scented spray called “Monster Go Away” that promises to banish scary creatures from under children’s beds or the depths of their closets.

Alzheimer’s patients at care facilities in Germany who feel the need to leave can sit and wait at a special bus stop outside the building until, five minutes later, they’ve forgotten they wanted to go home and the staff can invite them in for a cup of tea.

These are examples of deception used for good reason, to reduce distress. We are also used to being deceived for entertainment. Jokes often rely on re-interpreting what we think is true. Magicians’ tricks wouldn’t work without redirection.

Is it OK to Deceive Your Customers Online?

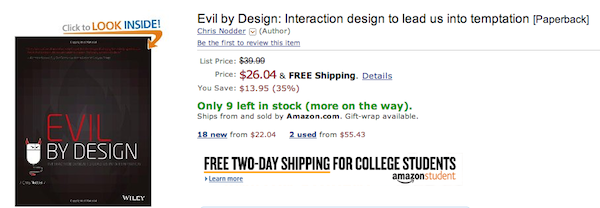

At the risk of reducing sales of my new book, Evil by Design, I’ll let you in on a secret: Amazon deceives you into thinking that my book is scarce, and that it must be selling really well, because it often looks like it’s about to sell out. “Only 9 left in stock.”

This is the Tom Sawyer effect. As Mark Twain narrates in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, “In order to make a man or a boy covet a thing, it is only necessary to make the thing difficult to attain.” It is also an example of social proof. If so many people are buying the book, it must be good, right?

Only nine left, so you had better buy yours right now—don’t delay or you might miss out!

In reality, Amazon keeps a very lean stock of most of their titles. It relies on regular shipments from my publisher, Wiley, in order to reduce its need for warehousing space. Unfortunately this sometimes leads to the book being out of stock (yes, it really did sell better than Amazon’s just-in-time algorithm predicted), but by-and-large this deceptive practice does little to hurt customers.

… it’s OK to deceive people if it’s in their best interests

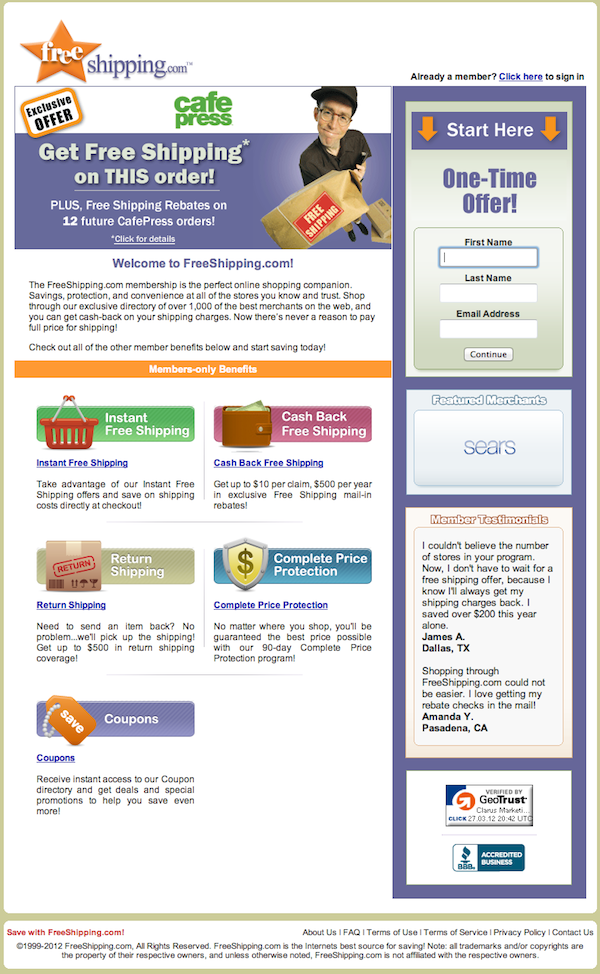

Other deceptive practices online are more likely to cause problems for customers. Sometimes, at the end of a checkout process at a reputable merchant, you might be tempted by an offer of free shipping on your next purchase, online coupons, or discounts. Often it’s hard to tell that this offer is made not by the online store you have visited but instead by a discount club run by companies such as Webloyalty, Vertrue, or Affinion. What isn’t made clear during this sales pitch is that you are signing up for a service that comes with a monthly membership fee, with few if any actual benefits.

On the face of it, this is a great offer from CafePress. In reality, it’s a sign-up form from a discount club that uses data pass-through to “share” the credit card details you gave to CafePress and subsequently charge you a monthly fee.

These companies lure customers in by first making something free to remove rational thought. They then lead people in along desire lines that hide important or government-mandated language in plain sight by pairing it with more attractive and visually rich paths through the process, or placing it below the action button. Finally, the subscription process is a negative option, meaning people are enrolled in the service by default, which makes it hard for them to realize that they are signed up and even harder to cancel.

Where is the Line Between Persuasion and Deception in Interface Design?

So where should we draw the line? The examples I gave above, and the persuasive design patterns they embody, can be used for either good or for evil. Most of our designs are trying to persuade people to do something: buy, sign up, contribute to a cause, or change a behavior.

Where on the continuum from evil to good are your uses of persuasion? And is deception allowable in those contexts? Just because persuasive practices can be used for deception, and just because deception can be used to do bad things doesn’t mean that persuasive techniques are necessarily bad in their own right.

I am suggesting that it’s OK to deceive people if it’s in their best interests, or if they’ve given implicit consent to be deceived as part of a persuasive strategy. People attending a magic show give this consent. The relatives of the Alzheimer’s patients give this consent (as probably would the patients if they were signing up for this care before their mental health deteriorated). Even the kids using Monster Go Away spray give their implicit consent. Children know that monsters aren’t real, but that doesn’t stop them from being scared. The solution is to give them a tool that fits in with their imagination. In other words, to meet the kids inside the deception they have created for themselves.

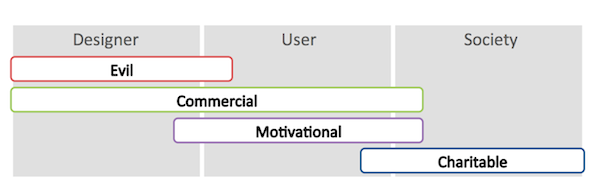

So then the trick is to work out whether the deception is in people’s best interests. There is a continuum of deception from evil through commercial and motivational to charitable. Of course, it’s easy to deceive yourself into thinking that you are designing a motivational or commercially persuasive interface when in fact it is evil.

The test is to ask whether the benefit to the individual or to society is at least as great as the benefit to you as the designer of the persuasive interface. The online discount clubs rake in a lot of money and give many people something they don’t need or didn’t even know they were receiving. Amazon makes cheap books magically appear within days of us ordering them online. Both use persuasive practices that could be seen as deceptive, but with a different level of benefit for their customers.

Who benefits most? Evil designs are aimed at giving the designer more of the value than customers. On the other end of the spectrum, charitable designs persuade customers to do something that benefits society more than it does them.

Are White Lies OK if They are in the Customer’s Best Interest?

I’m sure there are flaws in this argument. I can already think of several counterexamples. I’d love to know what you think. Do you agree? Disagree? What examples do you have of deceptive persuasive design being used either for good or for evil? Let me know in the comments, on twitter (@uxgrump with the #evilbydesign hashtag) or on my site, evilbydesign.info.

Image of magician courtesy Shutterstock.

Chris Nodder is the author of the insightful new book Evil By Design: Interaction design to lead us into temptation that delves into these persuasive patterns and more. He is a user researcher and interaction design specialist, and is the founder of Chris Nodder Consulting LLC, an agile user experience company that helps companies build products that users love. He also publishes techniques for agile UX teams on the Questionable Methods site. He previously was a Director at Nielsen Norman Group and a Senior User Researcher at Microsoft. He has a background in psychology and human-computer interaction.