Everyone loves a hero. But, what happens to organizations when their heroic leaders retire?

Four years ago, Bruce Mau Design (BMD) faced this dilemma. The company’s infamous founder, Bruce Mau, left so that he could create a platform to address bigger global issues that were meaningful to him called the Massive Change Network. Those who remained at BMD and its new President and CEO, Hunter Tura, were presented with an interesting opportunity: reinvention.

Curious about the culture of BMD today, I interviewed Tura in his Toronto office. Here are some takeaways for teams and organizations from their evolution.

Rethink Your Mental Model

Bruce Mau Design was founded upon what Tura describes as the “Superman model,” which meant the founder was seen as the “creative auteur” of the company. Mau’s exit gave the BMD team an opportunity to rethink how they positioned themselves, what services they wanted to offer, and how they wanted to work together.

Bruce Mau

Their biggest shift lay in the way they thought and talked about themselves. The absence of Mau meant that the remaining team owned creative authorship. Tura began playfully referring to this shift as the evolution from a Superman model to an Avengers model, highlighting the power that comes from the combination of the team’s different strengths and skills.

The Avengers analogy stuck and soon became an essential part of how they referred to themselves internally and externally. They found that this new identity also enabled frank, fruitful conversations with clients about why the transition was healthy for the organization in the long run.

Mau’s approach to design obviously laid the foundation for the BMD of today, from their intensive research to their ongoing work with arts, culture, and education institutions. When Mau left, the BMD team also decided to embrace some new ways of working that were more in-line with the “Avengers” they wanted to become.

For example, in Mau’s Incomplete Manifesto of Growth, he states, “Don’t enter awards competitions. Just don’t. It’s not good for you.” Today, however, BMD is not shy about this kind of recognition. Having won a spot on Fast Company’s 2012 Best Branding list for the “Know Canada” campaign, Tura says not only is it great for business, it’s meaningful to everyone who worked on that project.

The Avengers model also expresses itself in the more varied approach BMD takes to projects today. Rather than executing the vision of one project leader, the entire team might contribute to and influence creative direction. But if someone has a deep disciplinary expertise (such as working with educational institutions or libraries), then they might work one-on-one with the client to arrive at a vision. It just depends on the Avengers and client in question.

Changing external perception is no small task. Because they chose not to change the company name upon Mau’s departure, Bruce Mau Design may need to socialize their identity shift for many years before it takes deep root with the public. Or perhaps, public clarity isn’t critical to BMD’s long-term success. After all, people who hire Cooper don’t necessarily expect Alan Cooper to work on their project, nor are they likely to expect Robert Fabricant to participate in work done by Frog Design. But, what strikes me as most useful about this story of transformation is the potential power of a very simple, playful analogy. Superman and the Avengers are familiar icons, and paired together they communicate the old BMD versus new in a way that is clear, catchy, and memorable. Plus, the Avengers model instills pride and confidence in staff, sentiments critical to building an authentic, new identity.

If your team or organization needs to evolve its identity, here is a series of BMD-inspired questions you might explore in a brainstorming session: If you collectively embodied a superhero, which one would it be? Do you all have the same answer? Would you be proud of it? Does your internal identity match up with what the public perceives? If not, what are you going to do about it?

Let People Do the Work they were Hired to Do

In our conversation, Tura explained that as CEO, he sees his role as part curator, charged with finding the best talent for the Avengers team. Given Bruce Mau’s fame, Tura has noticed that people sometimes apply because they want to be a part of Mau’s legacy. But, says Tura, that can indicate a follower mindset, and he isn’t interested in applicants like that. He’s looking for Avengers; people who have superpowers of their own and are excited to share them. He also tells new hires that at BMD they will “do the best work of their lives.”

Within that statement lie both empowerment and an expectation of personal leadership that is vital to the Avengers model. It follows, then, that when a BMD intern created stellar work, he was asked to fly to Los Angeles with a creative director to co-present it to the client.

I think Tura is onto something. It’s no secret that empowered staff are invested staff. Of course, you have to hire go-getters. But there is another important reminder for leaders in Tura’s approach: too much top-down control risks squashing talent. If you believe people are good enough to hire, then you should have enough confidence to get out of their way and let them to do the best work of their lives.

Ask yourself: How well are individual interests aligned with the projects they are working on in your organization or team? Are they given a chance to express what they’d like to learn, be challenged by, or try through the course of a project? When I kickoff new engagements with teams, I always ask each person to share their answers to those questions so that we are all aware of how we can support one another’s success. If you aren’t already having that conversation with your teammates, you may be surprised by how much it can shift dynamics.

Assume Your Clients Know More than You

You could easily imagine that a group of shiny, new Avengers might inadvertently end up with giant egos (They are superheroes, after all) but I found the BMD team delightfully approachable and friendly. Tura also brought up an interesting way that humility plays a role in their work: “Meaningful does not equal meaningful to ME,” he explained. Their goal is to create meaningful solutions for their clients, and they do this, in part, by assuming that their clients have something to teach them.

This is a good reminder for the design industry. We aren’t experts in everything, most certainly the business of our clients. Design is by nature a collaborative process, and this requires that all players not only build upon their own expertise, but also grasp one another’s needs, goals, and motivations. It’s that level of communication and collaboration that gets great designs out into the world. Interestingly, as good as designers are at understanding the people they design for, they are often lacking when it comes to understanding their collaborators.

Here’s a tip: in our Design Leadership course at Cooper, we encourage people to create organizational personas to help them understand the mental models of their engineering, business, and marketing partners. Making the effort to understand your collaborators as well as you do your users will dramatically alter the experience of creating together.

Nurture Culture

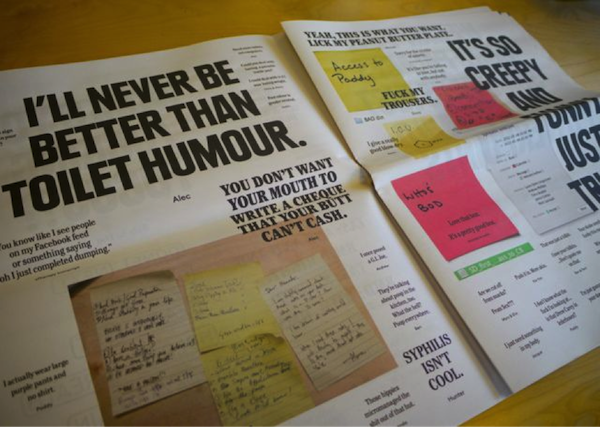

Imagine a newspaper filled with a hilarious collection of things staff said throughout the year, off-color messages scribbled on post-it notes, and a two-page photo spread of “twins” (a.k.a. staff who start dressing similarly after working together for a while). That’s the gist of the annual BMD Haiku book that is given to everyone on staff.

What I love about this artifact is that it’s about culture, and culture only. It’s not about profit margins or client work, it simply and powerfully creates a snapshot of what it was like to work together for a year. So often as we race toward deadlines and profit goals, we forget that we are people. It’s incredibly important to nurture our relationships, play with one another, and connect as human beings … because those bonds are what get us through the rough spots in projects.

So, what are you doing as a team or organization to celebrate, laugh, and nurture your culture? Do you have an explicit way to reflect upon the quirky uniqueness of your group? Are you making time to socialize and get to know each other?

What are you doing as a team or organization to celebrate, laugh, and nurture your culture?

There are a million ways to create stronger connections. For example, if you’ve had a particularly tough week at Cooper, you earn temporary ownership of a stuffed fish and a chance to make light of your angst with everyone.

I know teams that have “Grilled Cheese Fridays,” go jogging together at noon, and have bad idea contests. The most important thing is that you instigate ongoing practices to keep culture alive.

“Growth happens. Whenever it does, allow it to emerge.”—Bruce Mau

In closing, there are many ways BMD could have addressed the departure of their founder. They chose to embrace that change and become a new kind of organization, driven by a group of superheroes. That decision impacted how they perceive themselves, create, and interact with clients. So far, it seems to be working. And no matter how it turns out, you have to give them credit for owning change, rather than letting it own them.

As Alan Cohen said, “It takes a lot of courage to release the familiar and seemingly secure, to embrace the new, but there is no real security in what is no longer meaningful. There is more security in the adventurous and exciting, for in movement there is life, and in change, there is power.”

Sometimes, change is a catalyst for organizations. Sometimes, when leaders retire, those who remain build from the legacy and blossom.

If this article inspires to transform your work culture, check out Cooper’s Designing Culture workshop and this collection of tips for creating inspired work cultures.