Save

Control of personal information in the digital space, and particularly on mobile devices, presents a unique design challenge.

Most people aren’t aware that their personal data is being collected and shared. Many users don’t take the time to validate their expectations and most never read privacy policies.

People only seem to become aware of such concerns when something happens that doesn’t meet their expectations, such as seeing their friend’s picture in a Facebook ad or seeing banner ads that match their most recent purchase. And when people do become aware and their expectations are violated, trust in the brand is eroded.

People want transparency and control, but they want it on their terms. They don’t want to have their activities interrupted, but they do want to set controls on what’s being collected and how it is used. From these realizations, the Digital Trust Initiative—an independent effort studying design and privacy policy in digital technology—was born.

The Goal

The goal of the Digital Trust Initiative is to create awareness of privacy issues while not getting in the way of the user experience. This is an even bigger challenge for mobile devices because of the small screen real estate and the need for consistency across apps and sites. However, it is not insurmountable.

By leveraging visceral design constructs such as sound and vibration, we can create new experiences around personal data collection that are both transparent and provide control. But before we can begin to think about design solutions, we need to understand consumers’ current experience and expectations of how their personal information is handled and safeguarded.

What Misconceptions Do Consumers Have?

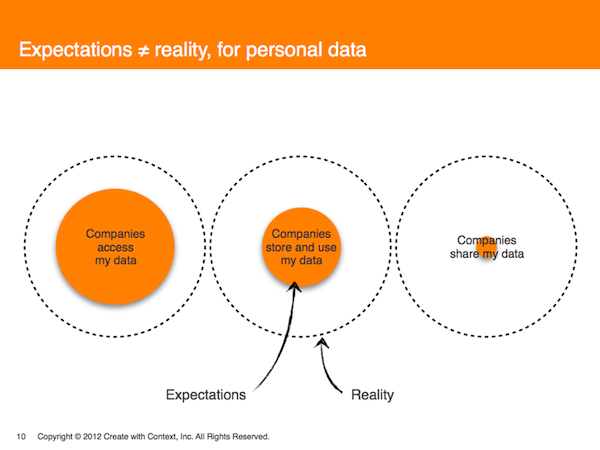

Through our research with consumers in the U.S., Mexico, and Canada, we found that consumer expectations do not map to reality. In the online interaction between consumers and companies, consumers do expect that companies access their personal data in order to complete transactions, and their expectations match reality. However, user expectations and reality diverge when it comes to companies’ storage and use of consumers’ personal data. A nearly total mismatch occurs when it comes to sharing people’s personal data: companies do far more of it than most consumers realize.

This lack of awareness leaves consumers vulnerable. If they don’t realize that their data is being accessed and shared, they are unlikely to try to look for controls to set their preferences. While people understand that they can control what personal information other consumers see, they have little awareness of their ability to control how companies use, store, and share their data.

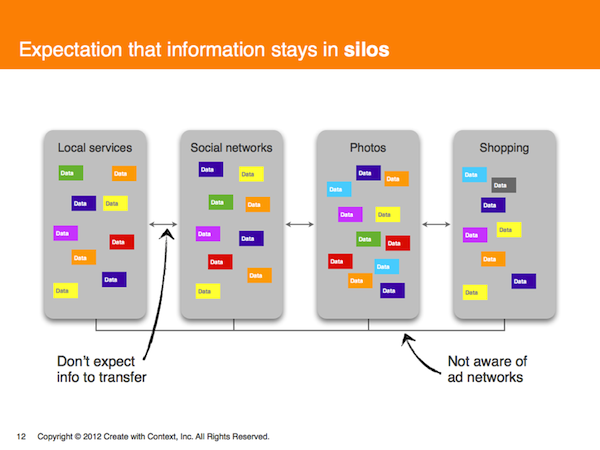

What consumers do expect is that information stays in silos. Aware of all or some of the possible online data collectors—such as local services, social networks, photo-sharing sites, or shopping sites—users think that their data remains only with those sites. They don’t expect that their personal information is transferred between them. Most consumers are also not aware of ad networks that may gather data across all sites they visit.

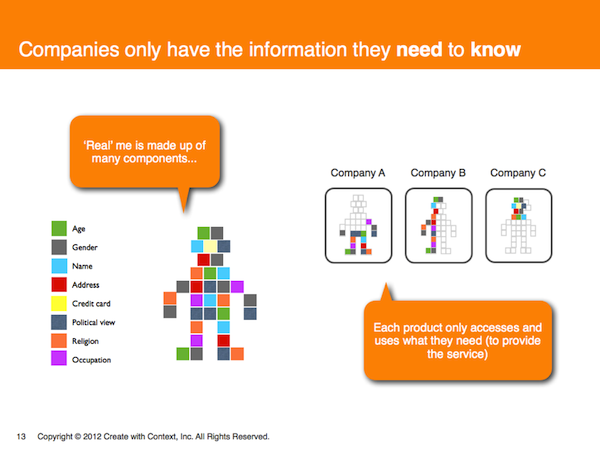

Consumers believe that companies only have access to limited personal information. In some ways, users feel that this is a form of protection, since the “real” me is made up of many components. Consumers only give each online site data about themselves that is relevant to that transaction or service, and assume that sites don’t know the “whole” me.

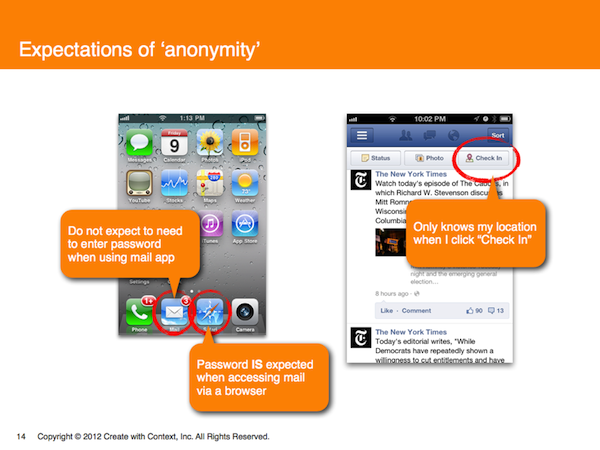

People have expectations of anonymity on sites until they provide authentication. For example, consumers believe that they are anonymous when shopping on the Internet until they choose to give their personal information. They believe that their provider or a site only knows their location when they “Check In.” And while people expect to provide a password when accessing mail via a browser, they do not expect to need to enter password when using their mail app.

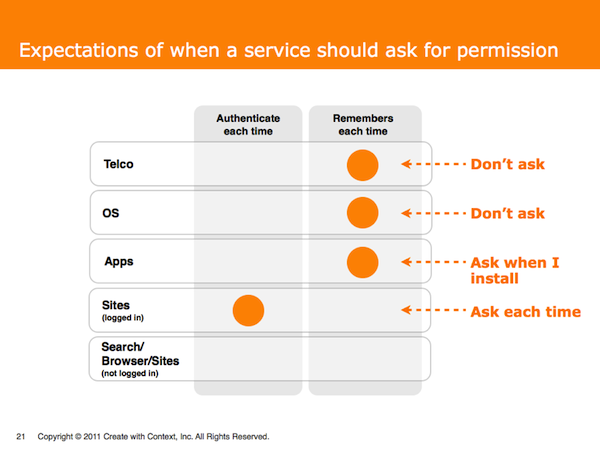

Consumers expect that sites should ask for their information each time they visit. By contrast, users believe that providers and operating systems don’t need to ask each time, and they expect apps to ask only at time of installation.

How do Consumers React?

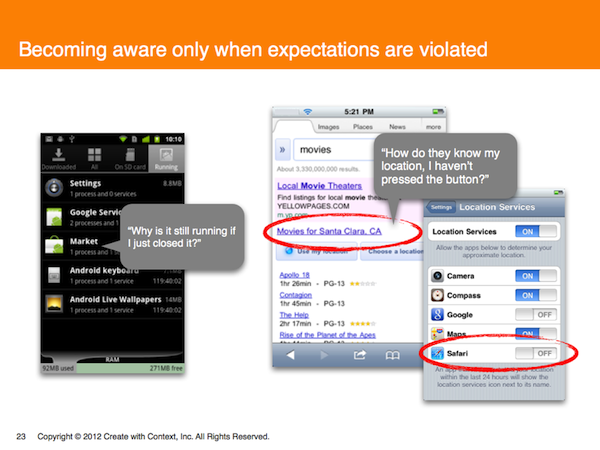

The crux of the situation, and the impetus for DTI, is that consumers now only become aware of data collection practices in a negative way: when their expectations are violated. With the significant mismatch between expectations and reality outlined above, this is bound to happen. But consumer reactions to a sense of intrusion run from mildly upset to strongly upset.

For example, if a consumer sees that a shopping app is still running, they might wonder: “Why is it still running if I just closed it?” Or on the provider’s opening page, if it already knows the user’s location they might as themselves: “How do they know my location? I haven’t pressed the button!”

Privacy policies can also create distrust. Because of the dense text, consumers typically don’t want to read them, and when they do, they have strong reactions to what they learn. Their biggest concern is that primary sites would share data with third parties and not be “responsible” for how it is used by those third parties.

“Wow, that’s not cool,” is how one person put it.

Not only are privacy policies dense, their legalese is often difficult to penetrate. Companies gain consumers’ trust when their privacy policies use plain English rather than technical legal language.

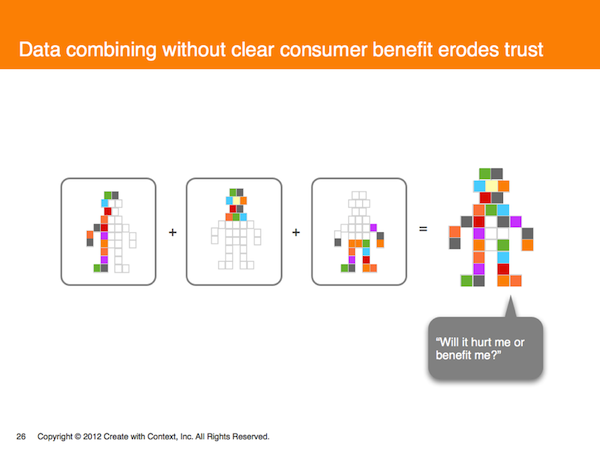

Combining consumer’s data—putting together the different pieces to understand the “whole me”—without clear consumer benefit erodes trust. There is a fine line for consumers between a helpful, personalized suggestion and one that feels invasive, like the site knows too much about them. People wonder, “Will it hurt me or benefit me?”

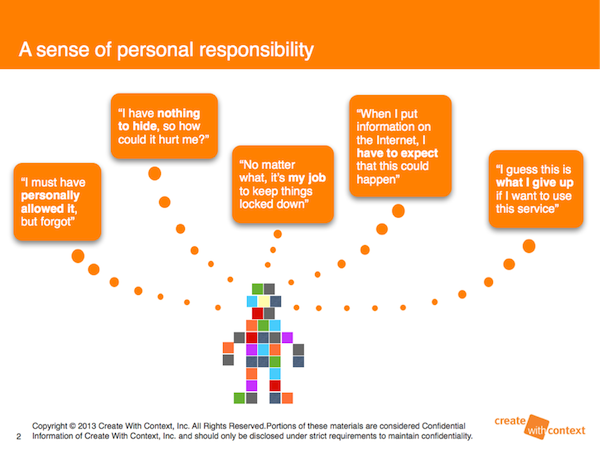

People shoulder the blame for having given up their personal information. They sense that it was in their control, but they dropped the ball. They cycle through a self-recriminating thought process:

Discovering that one has lost control of personal information triggers a version of “nothing is free”—a sense that one has to give up privacy to get the service. This is invariably an uncomfortable tradeoff, creating a sense of disappointment rather than delight. Some consumers ultimately opt out rather than agreeing to this tradeoff.

What Do Consumers Care About?

People want a sense of transparency and control when in the online space.

- Transparency means that consumers clearly understand what is happening while they are using a service. It means that they don’t “find out” after the fact, or from another source, that they inadvertently shared personal data.

- Control allows people to opt in or opt out of data sharing in and beyond the service, or of using the service at all.

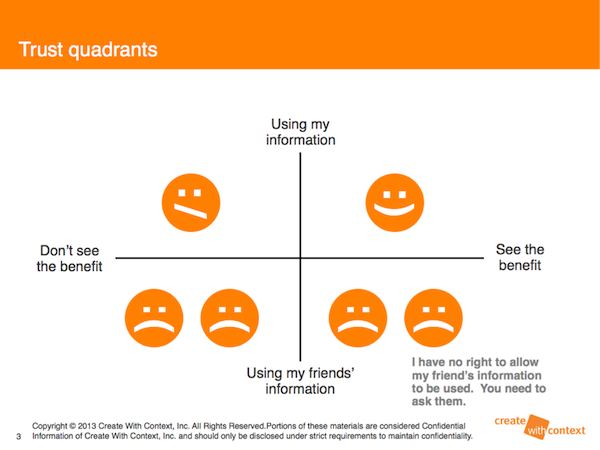

Consumers also care about protecting their friends’ personal data. While they may see the benefit to themselves in sharing their own personal information with a site, they don’t want to be responsible for revealing their friends’ information. They feel that “if you’re grabbing my address book and friends info, that’s not cool.”

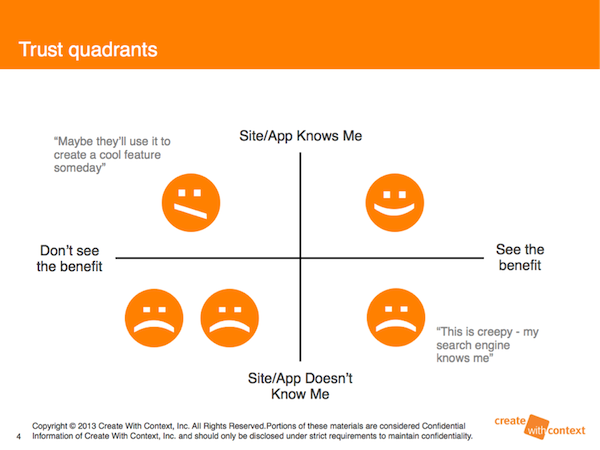

Similarly, with authentication, some consumers see the benefit in having a site or app “know” them: “Maybe they’ll use it to create a cool feature someday.” But again, for others, “This is creepy: my search engine knows me.”

Interestingly, people are less concerned about location tracking when a company is doing it instead of an individual—a “creepy stalker.” In fact, people like targeted advertising. For example, if you’re in the market for a mattress, it’s great to get special offers on mattresses pushed to your inbox.

Some consumers allow location tracking even if they are unaware of the benefits, considering it just part of the “flow” of online shopping.

Those who don’t expect that their location is being tracked are not typically upset when they discover that it is. They don’t see how it could hurt them if it is used for marketing purposes. However, they will turn off location tracking if it is convenient or if they notice that they’re being tracked.

But in general, consumers do not continuously check to make sure tracking is off.

Conclusion

Our findings from foundational research with consumers shows how their expectations around digital privacy and the corresponding realities are often mismatched. As a result, consumer reactions to reality can be strongly negative. Focusing on what consumers truly care about—transparency and control—will provide the springboard for developing innovations and finding solutions that earn brand trust in the personal data sharing space.

The Digital Trust Initiative is an independent effort to study digital design and privacy policy in digital technology. The work of the initiative is funded, in part, by a variety of partners: Yahoo!, Create With Context, AOL, The Future of Privacy Forum (FPF), Verizon, and Visa. The views expressed in this article and the conclusions drawn do not reflect the views of these partners. Further, the partners have not independently verified the results of the study, nor do they make any representation as to the accuracy or value of any statements made herein. For more information, please contact [email protected].

Image of girl with vintage camera courtesy Shutterstock

Ilana Westerman has for the past 15 years focused on helping bring people and technology together through seamless digital experiences. At Create with Context, Ilana leads strategic research and idea generation for global Fortune 500 companies.

Ilana also shares her passion for research-driven design as a part-time faculty member at San José State University, where she has taught graduate level courses in the Industrial Systems Engineering/HFES program since 2005.

Previously, Ilana performed strategic user research at Adobe, helping envision and define future products focused on digital youth and creativity.

Prior to that, Ilana joined Yahoo! in its infancy and helped build the User Experience Research team, managing Community, Cross-platform, Mobile, and Living Room experience teams. Her group defined the strategic direction of Yahoo! with projects including Future of the Internet (3, 5, 10 years out), Platform Convergence, Internet Everywhere, What Can Be with Yahoo! Mobile, and Global Yahoo! Platform.