Save

The first rule of e-commerce is, make it easy for people to give you money. But a ubiquitous practice on e-commerce sites breaks this rule big time: When users click/tap “Check out now,” sites intercept them with a demand that they first create an account or log in to an existing one. By requiring users to have an account as a prerequisite for making a purchase, they are telling would-be buyers, in effect, “Unless you have an account, we don’t want your money. Go away.”

So lots of willing buyers—credit cards in hand—go away. For these sites, would-be sales gush out of a big hole in their bucket. Lately, more and more major online retailers have backed away from their account requirement. But roughly 3.2 gazillion others still have it. And even those that have backed away from it have clung to a needless vestige of it: the intercept itself, though now modified to include a third option, checking out as a guest.

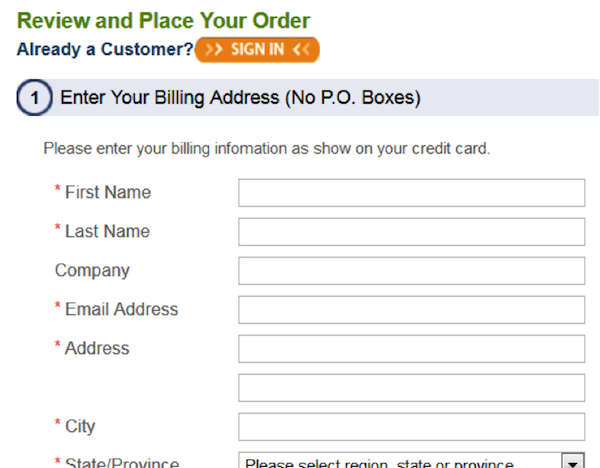

Here is a typical intercept:

If your checkout flow is preceded by an intercept like what you see above–with or without a guest checkout option–it is probably costing you far more sales than it gains you. Adding guest checkout only shrinks the hole in your bucket. It doesn’t plug it.

You should nuke that intercept entirely.

Typical Checkout Flow

Every e-commerce checkout process does things a little differently, but here’s a typical workflow:

- You click/tap an action button such as “Check out now.”

- You land on an intercept that requires you to choose between creating an account, logging into an existing account, or (often) checking out as a guest.

- You now enter checkout proper, where you answer the first set of questions, typically how and where you want the merchandise shipped.

- You answer a second set of questions, typically how you will pay.

- You might review everything and possibly answer some additional questions.

- You click/tap an action button such as “Place order,” then get some kind of confirmation that the order went through.

- You start getting marketing emails, even if you never got past the intercept.

About that last step: how effective is that email marketing going to be? If you just made 100 sales, how many additional sales will your email marketing produce? The answer I typically hear is somewhere in the neighborhood of 1% to 2%. To be generous, let’s call it 2%. So instead of 100 sales, you get 102 sales.

Drop-Off

As meager as that payoff is, it’s only half of the story. At every step along any online process, there’s going to be some amount of drop-off: users who, for whatever reason, don’t reach the next step. In checkout, there are two kinds of drop-off:

Inevitable drop-off happens for reasons like these:

- people were never really serious about purchasing in the first place

- they got into this process by mistake

- they remembered that they can’t afford this purchase right now

- their computer crashed

- your system crashed

- the baby cried, and they never came back.

There’s little or nothing you can do about those kinds of things.

Avoidable drop-off, by contrast, is the result of you getting in the user’s way: choosing to obstruct their path with hurdles, distractions, and irritants that prompt them to leave. Like, oh, say, an intercept. You can choose to remove such elements.

Remove them? Heresy! After all, the intercept is what captures the email addresses that make possible the email marketing that bumps sales up from 100 to 102.

Half-Math

Focusing on the two additional sales that your email marketing gains you is a textbook case of what I call half-math: Looking only at the payoff but not at the cost (or vice versa, but that’s a different discussion).

It’s like saying you won $1,000 playing poker in Vegas. It may be perfectly true, but it is only half of the equation: Full math factors in the $3,000 that you lost at the same poker table and the $800 that your flight and Vegas hotel cost. So, sure, you won $1,000—but let’s not kid ourselves: You had a net loss of $2,800.

Don’t try to improve your intercept. Drive a stake through its heart.

Likewise, your gain from email marketing is hardly free money. Capturing those email addresses at the intercept cost you something: avoidable drop-off. And your gain from email marketing is meaningful only in comparison to your cost in drop-off. Full math.

What is your own site’s drop-off between your intercept and step three, the beginning of actual honest-to-gosh checkout? If you don’t know, cancel your next meeting and go find out.

When I give talks on this topic, I ask the audience to supply the intercept’s drop-off rate. The rates they volunteer are typically 25% to 50%. I’ve even heard 75%. Sites that require an account are probably the ones with the highest drop-off. To be conservative, let’s call it just 25%. This includes people who:

- don’t want no stinkin’ account and bail out when they gather (rightly or wrongly) that you’re hitting them up for one

- are puzzled or put off by the intercept and bail out

- don’t want to get spammed

- use the same password everywhere and don’t trust you enough to hand it over

- get tired of waiting for a slow screen load

- can’t be bothered with the extra effort you are foisting on them

- try to create an account, but fail for some reason

- try to sign in, but fail for some reason

- ask for a password reminder or reset, but your reminder/reset email goes to their spam folder and they never find it

- receive that email but then either strike out on their second attempt too or never bother to come back at all

Whatever the reasons, for every 100 people who click “Check out now”—who are, by all intentions, very serious about giving you money—25 never make it past the intercept. They give you no money at all. You broke the first rule of e-commerce.

Sales Tomorrow Versus Sales Today

So why is the intercept there in the first place?

The answer I generally hear from marketing folks is that its purpose is to make sure we capture email addresses up front so that, whether you complete the purchase or not, we can market to you. And why do we want to market to you? In hopes that maybe you’ll buy something tomorrow. We’ll get those two additional sales.

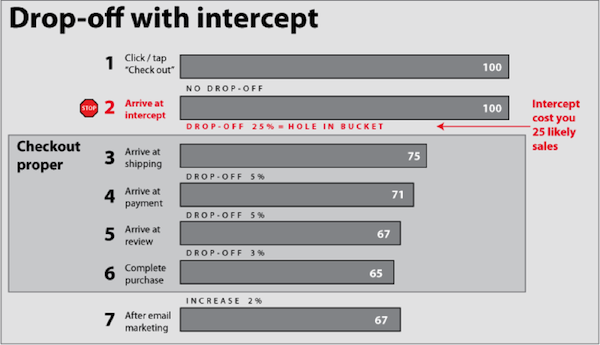

OK. Let’s graph that, along with fairly typical drop-off rates at the steps between the intercept and the email marketing bump:

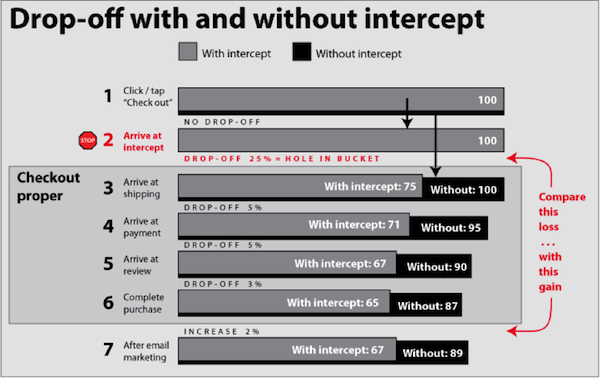

Now let’s compare our drop-off WITH the intercept to the drop-off we would have WITHOUT the intercept:

Remind me again why that intercept is there? Oh yeah, to bring us two additional sales.

In other words, our intercept drove away 25 near-certain sales right now in order to gain the prospect of two sales tomorrow. Is there some parallel reality in which this makes sense? Would you pay $25 for two crisp new dollar bills? Would you pay $25 million to a sales person who brings in $2 million in sales? No? Then why would we quietly accept a 25% loss for the sake of a 2% gain?

Half-math, that’s why. Not looking at both numbers.

That drop-off from the intercept is the gushing hole in your bucket. No marketing on earth can make up a loss like that.

Now, suppose I’m way off-base. Suppose your marketing is so savvy that your multiple waves of emails and other uses of email addresses from the intercept give you a sales bump 10 times greater than the 2% figure I’m using. Fine. That would bring the payoff up to only 20 sales, still at a cost of 25 lost sales—still a losing proposition.

Your actual numbers will differ from the ones I’ve been using. How will your intercept’s drop-off and your email marketing bump compare? I don’t know, but I’ll bet you next week’s salary that neither does a single soul at your company.

Always Assume Guest Checkout

Fortunately, the problem is completely needless and sublimely easy to solve: Always assume guest checkout.

That’s it. Don’t intercept, don’t ask, just assume. When anyone clicks/taps “Check out now,” take them directly to the first step of checkout proper (shipping, billing, whatever). No intercept. No prerequisites. No song and dance.

More and more sites seem to be using that flow. A few examples: aBookApart.com, specialtys.com, Solutions.com, RickSteves.com, purefixcycles.com, competitivecyclist.com, and threadless.com. Take a look at how hammacher.com assumes guest checkout:

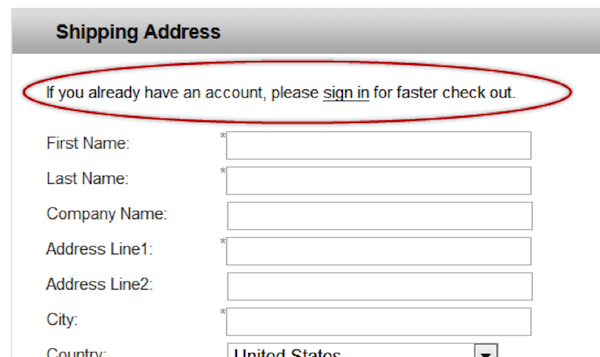

Notice I’m not saying to stop having accounts. They can be a fine convenience for frequent buyers and others who want them. I’m just saying to stop shooting yourself in the foot. Come up with some less counterproductive way to get and utilize accounts. The first step of checkout proper should certainly include an optional login widget like hammacher.com’s above for those who choose to log in. And the confirmation message—i.e., AFTER the sale has been concluded, not before—should certainly suggest creating a password to speed up checkout next time. But never ever let the prospect of an additional sale tomorrow scuttle an actual sale today. Don’t try to improve your intercept. Drive a stake through its heart.

You’re Still Getting Email Addresses

What about marketing’s determination to get all those email addresses? Just make email address one more field in the checkout form itself.

Done.

You’ve now accomplished everything the intercept did, but without its drop-off. And by having not turned away a quarter of your would-be buyers at the start, you will probably wind up with more email addresses all told than your intercept was yielding. Here’s one example:

If the prospect makes you nervous, run a small A/B test. For a period of, say, a month, omit the intercept for 5% of users who click/tap “Check out now.” Keep it for the other 95%. For each group, track the percentage who complete a purchase. At the end of a month, compare the two numbers.

If the numbers persuade you to drop the intercept, you will be in good and growing company. And you will have made it easier for people to give you money. There may be shrieks of horror in the hallway at the very suggestion of dropping your intercept. But it may well be the single most lucrative move you could possibly make.

Image of old rusty bucket courtesy Shutterstock.

John Boykin

John Boykin answers to user experience designer, information architect, interaction designer, information designer, and UX researcher. He’s been doing all of the above for over 10 years. Clients include Walmart, Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s, Blue Shield, Bank of America, Visa, Symantec, NBC, HP, Janus, Prosper, and Mitsubishi Motors. His site, wayfind.com, will tell you more than you want to know.