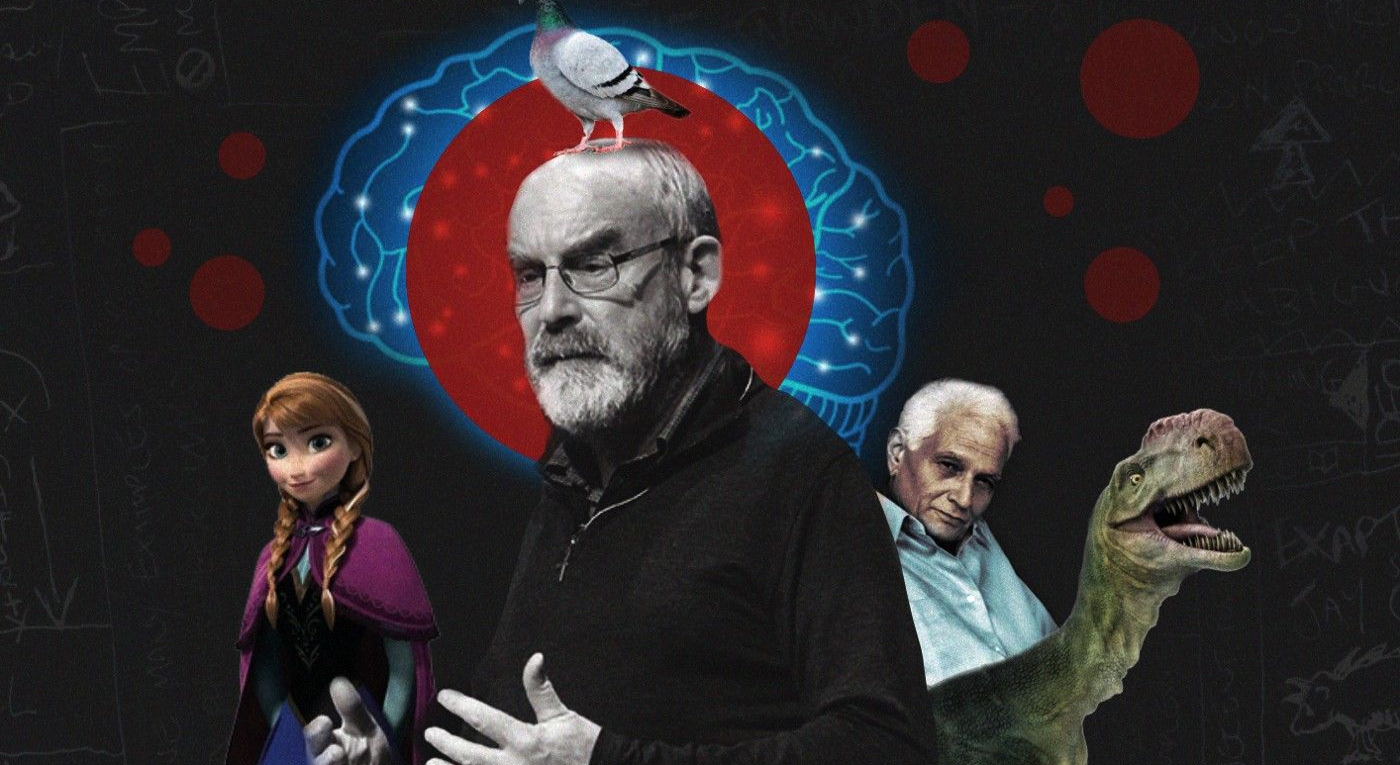

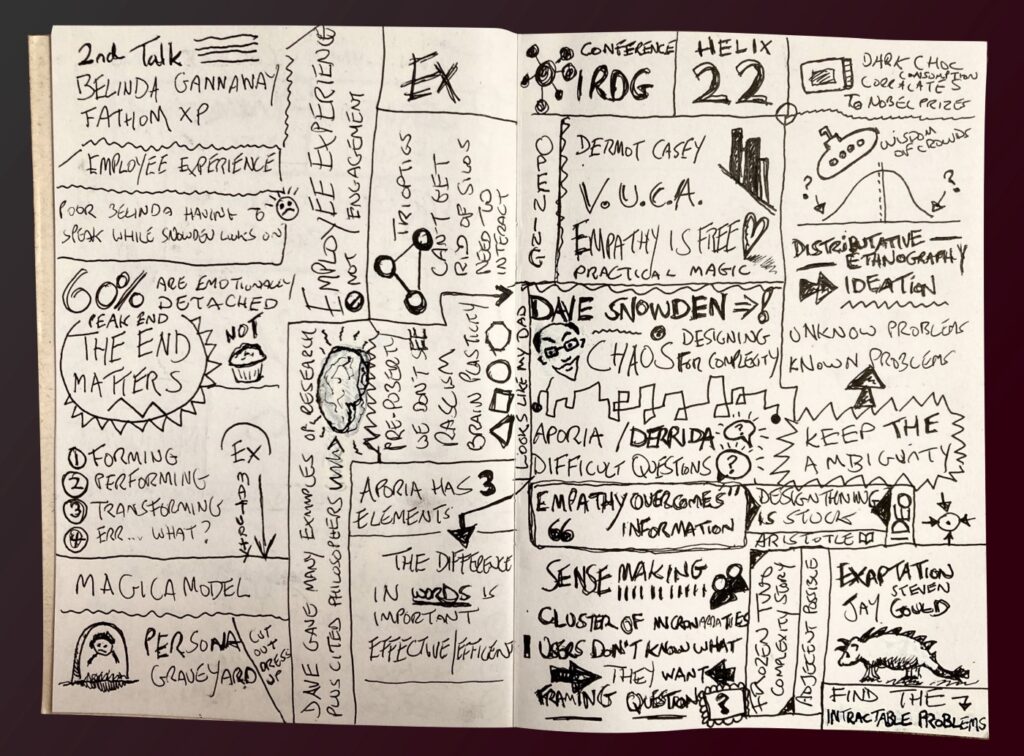

Dave Snowden developed his Cynefin framework over many years, a powerful decision-making framework that attempts to give us tools to absorb uncertainty, create resilience, and thrive in a complex world. I was enthralled by a talk he gave at Designing Thinking Ireland. Whether you can take his direct style (he isn’t afraid to tell you when he thinks you’re wrong), his talk was overflowing with rich ideas that quickly filled my sketchbook. Here are some unprocessed insights I reconstructed from my notes.

Consciousness is a distributed function

Abandon all computer metaphors for how humans behave. The Cartesian mind-body dualism can be a dangerous metaphor. Consciousness is a distributed function of the brain, body, environmental factors, and social interactions and is not co-located solely in the brain. The metaphor about rewiring the human brain makes little sense, as we should see it more like the brain making connections in different ways.

That’s chaos and complexity right there. If you think you know what’s really going on, you don’t. Get used to it. Embrace it.

Dark chocolate consumption and Nobel laureates

The New England Journal of Medicine noted that dark chocolate consumption could hypothetically improve cognitive function not only in individuals but in entire populations. There may be a correlation between a country’s level of chocolate consumption and its total number of Nobel laureates per capita, but alas, there is no proof, with issues with over-interpreting correlations in the research. Not very useful, but what a nice thought.

Derrida and aporia

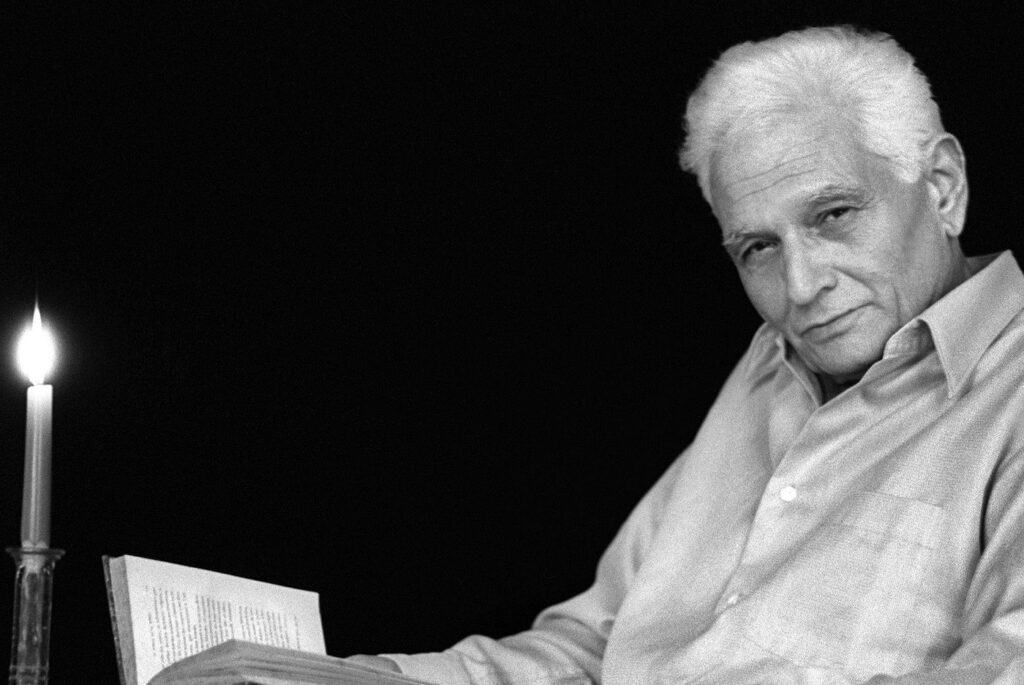

Aporia, taken from Jacques Derrida’s concept, means ‘impasse’ or ‘puzzlement’.

In Derrida’s famous phrase, ‘if you know the answer to a question, it isn’t a question, it’s a process.’ Aporia are questions that can’t be answered without thinking differently.

The seeking-out of those aporias, blind spots or moments of self-contradiction where ‘a text involuntarily betrays the tension between rhetoric and logic, between what it manifestly means to say and what it is nonetheless constrained to means.’

Aporia brings a tension into knowing and not knowing. It’s a transition and allows us to become beginners again and stops us from jumping to conclusions.

Derrida was an interesting and highly controversial figure, developing a philosophical approach called Deconstruction. It’s about oppositions and his approach brought about the ‘death of the author’. In a simplistic sense, he sought to analyse literature, seeing that text does not have a fixed meaning. ‘If the bottle’s colorlessness was taken for granted by people as the default nature of milk bottles, painting it red deconstructs this prevailing perception.’ Deconstruction become de rigour in English Lit departments during the 1980s and the approach found favour in trendy graphic design circles in the early 1990s. It’s nice to wheel a French intellectual out every now and then.

Design thinking?

Dave seems to be a critic of design thinking as practiced by companies such as IDEO. It stems from some negative experiences he had in design thinking workshops, packaged and commodified into a one size fits all mantra.

As he says, ‘my feelings on traditional design thinking are similar to my feelings on the whole SCRUM method, namely they both have value but they are linear and involve pass-offs to experts at critical phases in the process.’ In a design thinking session he attended felt that ‘there was a little too much control for my mind and at the end of the day we were told that the experts would now go offline and present solutions to us in the morning.’ He feels that the subject is not fully involved in the full process and that ‘experts’ mediate the findings by introducing bias.

There are many tools out there to get the job done, with Design Thinking being just one of them. Big corporations push it because it makes money, and it’s easier to adopt and justify over having a multi-layered approach. I have noticed that momentary pause from designers when I tell them I favour a less prescriptive approach and I don’t use the Design Thinking process on everything I do. Design Thinking is not the be-all and end-all in design land. Did I say something controversial?

Distributive ethnography

Ethnography is the scientific study of cultures, people, and their customs. Distributed ethnographic allows for large-scale capture into a quantitative framework, where the ‘subject’ becomes their own ethnographer. This approach, which Dave calls SenseMaker®, combines the scale of numbers with the explanatory power of narrative.

Well organised distributed ethnographic takes vast amounts of data, mines it for context and narrative, that comes directly from stories of real people. It brings with it the power to empower people to interpret their own narrative and avoid the epistemic injustice of third-party or algorithmic interpretation.

Embrace ambiguity

There is a difference between having a direction and having a goal. In a complex situation with many moving parts, goals can be dangerous, as they can lead to inflexibility. If you start a journey with a sense of direction, you stay open to change, novelty, and quickly adapt. Embracing ambiguity doesn’t give you the right answer, but is gives you better ones while showing you which are wrong.

This brings to mind the phrase ‘don’t sweat the details’. Our obsession with setting our design process into stone hampers us. We should be unafraid to say that we don’t know everything, and still discovering things, when we are looked to for complete certainty.

Exaptation

In 1982 Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth Vrba introduced the term ‘Exaptation’ to describe the process by which character traits do not evolve in the context of current use but to serve a different function or may have evolved as a byproduct of the evolution of a different feature.

Random mutations led to the evolution of feathers used for warmth, and by chance those feathers then become useful for flying like the first creature to take flight, the Archaeopteryx.

In 1942, Percy Spencer was a scientist who was testing out a radar magnetron when he noticed that a peanut cluster bar had melted in his pocket. The microwave was born.

History of the web is continuous exaptation. Tim Berners-Lee invented the world wide web for academic purposes, but it evolved into unanticipated areas. Corndogoncorndog.com anyone? The unanticipated weirdness is never ending.

Look at what we create, and see if we can combine things in the periphery of our thoughts to make something new and exciting.

Falcon and the pigeon

Dave is fond of using a tale from The Exploits of the Incomparable Mulla Nasrudin by Sufi writer Idries Shah to illustrate his frustration with design thinking in large organisations.

Nasrudin found a weary falcon sitting one day on his window-sill.

He had never seen a bird of this kind before.

‘You poor thing,’ he said, ‘however were you allowed to get into this state?’

He clipped the falcon’s talons and cut its beak straight and trimmed its feathers.

‘Now you look more like a bird,’ said Nasrudin.

What Dave means is taking his thinking and trying to funnel it into whatever process a company has been doing, which will end up with the same results. Push back on the desire for uniformity in our design thinking.

Frozen Two and the adjacent possible

He loves Frozen Two and says that this children’s film explains complexity theory perfectly. During the film, Anna, the younger sister, the real heroine of the series, is in despair because she has lost her sister and she must fend for herself. She sings a song called The Next Right Thing. For Dave, this song contains the central message of complexity theory called the adjacent possible. In fact, the whole of that movie is a great illustration of complexity!

First popularised by evolutionary biologist Stuart Kauffman in 1996 to explain how new possibilities may sometimes lead to explorations of different but associated subjects. Vittorio Loreto defines the adjacent possible as “the set of possibilities available to individuals, communities, institutions, organisms, productive processes, etc., at a given point in time during their evolution”. Steven Johnson popularised the concept by showing that innovations result from a recombination of things in the sphere of science and technology development.

So what good is it? Well, we can use what we have to create new things. Simple as that.

Order, complexity, and chaos

Ordered system

A high level of constraint, structure, and behaviour is predictable. These are ‘known knowns’ and call for best practice.

Complex systems

Everything is entangled with everything else in a complex system. To use Alicia Juarrero’s phrase, ‘like bramble bushes in a thicket’. You know there is some structure in there, but you can’t discover it. There is no linear causality, and if something happens twice, it is coincidence and by accident. Known unknowns.

Chaotic systems

Has no constraints and is pseudo-random. Much like in physics, with phase shifts from solid, liquid and gas.

The current pandemic has highlighted the need to act in complex and chaotic times where the level of uncertainty is high. One of the key challenges faced is that most organisation have oriented themselves to work as if the world is predictable where cause and effect are clear. Traditional best practice approaches fail, and existing governance structures can’t cater to complex or chaotic situations.

How I apply this to the design process

- Do not innovate when the path is clear. Use well-established patterns. The job is to find a solution to the user’s goal, not innovate on design details that do not add value. Take, for an example, a login screen. The login is not something I should design in a flow.

- It shows me what I should not be wasting time on. I shouldn’t be trying to innovate a login screen, that’s not the goal. The framework recommends the use of well-established patterns, such as using existing components for something as simple as a login screen.

Sense-making

Dave defines it as “how do we make sense of the world so we can act in it” which carries with it the concept of sufficiency (knowing enough to make a contextually appropriate decision). It is about making sense of an ambiguous situation. The Cynefin Framework is a sense-making approach.

Triopticon

Now I’ve heard of the panopticon, first proposed by Jeremy Bentham, a jail allowing for the watching of the inmates around the clock and from any angle. French philosopher Michel Foucault then used the panopticon as a metaphor for our modern surveillance society. Anyway, I digress.

The triopticon is much more benevolent than this. Dave was interested in developing a new type of facilitation based on high levels of interaction and transparency, which includes eagles, ravens, beavers, and owls. No, really. You can read more about the process in The Triopticon Revisited.

Wisdom of Crowds

American journalist James Surowiecki first suggested that the best way of finding a solution to a problem is by asking many people for their opinions and suggestions, and then combining them to form the best overall decision. Evidence suggests that the combination of multiple independent judgments is often more accurate than even an expert’s individual judgment.

It shows that bringing in people with different disciplines to the design process as early as possible can be beneficial.

References

A Derrida Dictionary, Niall Lucy

Dave Snowden on Liminality in Cynefin and Moving beyond Agile to Agility, InfoQ

Does Chocolate Consumption Really Boost Nobel Award Chances? The Peril of Over-Interpreting Correlations in Health Studies, The Journal of Nutrition

Internalized Authority and the Prison of the Mind: Bentham and Foucault’s Panopticon, Joukowsky Institute

Mischief, thou art afoot, Dave Snowden

The Exploits of the Incomparable Mulla Nasrudin, Idries Shah

The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter Than the Few and How Collective Wisdom Shapes Business, Economies, Societies and Nations, James Surowiecki

We say chocolate is the mother of invention, The Chocolate Truffle

Unfolding the dynamics of creativity, novelties and innovation, Vittorio Loreto