“It can’t be that people only want to work with Lindsey’s team because she’s nice to them, we need a strategy for this.” — A colleague.

Not only is compassion a strategy, in this moment, it’s the only one I know that works, that offers a glimmer of hope to move forward. My management experience has been formed by crises. I transitioned into managing in June of 2020, right at the beginning of the Covid 19 pandemic, at the time of George Floyd’s murder and right before California (where I lived) caught on fire for months.

I also live in the United States of America.

This means that about 3 weeks ago I learned that the Supreme Court was ready to throw out Roe vs. Wade, along with potentially all the other decisions giving women the right to bodily autonomy and reproductive health care.

A week ago 10 people were gunned down in a grocery store in a segregated city, targeted for the color of their skin.

Tuesday 19 children and their teachers were murdered in their classroom. We’re now learning the police stood by for an hour, tasing parents who tried to get to their kids while every single 4th grader in a class died.

This is just the last month of more than two years of mass death and national terror. I say this as a white woman writing with a huge amount of privilege and as a parent who had two small children out of school for over a year.

The traumas of the past few years have not been evenly distributed and every single person I interact with at work and who I lead has intersecting identities that have shaped their experiences of the past few years. No one has come through unscathed but part of managing through this era has come with a keen awareness of the ways that the weight of our crises affect my teammates and colleagues differently. I want to speak about my personal experience in this article, but I think the points I make are not just about me, and I hope some will resonate with you and help us reimagine how we work together to create teams and organizations that foster not just “human centered design” but creating organizations and structure that help people thrive rather than crushing them.

Becoming a manager and nurturing teams through these times has made me realize the business value of compassion, kindness, and building positive relationships. We don’t often talk about this “squishy stuff” at work, but these are the things we need to work successfully these days. I argue that compassion for ourselves and others in the workplace isn’t a “nice-to-have”, it’s a “need-to-have” that is often the difference between resilience and success or failure and burn out. This is true for everyone, but especially for managers.

Storytime:

For most of my adult life, I prioritized work over my physical and mental health, it’s how I was taught. I’m not just talking about paid work, but all work: school work, paid work, and parenting care work. I went from being the kid who calls their professor from the hospital to tell them I’d be missing class the next day because I was getting my appendix out, to being a mother of small children learning things like how to breastfeed with the stomach flu, and that it didn’t manage how tired you were, you still needed to get up whenever your kids needed you, and how to push a stroller with a baby in it while carrying a screaming toddler and a balance bike. When I started working in tech, I became someone who refused to cancel meetings or business trips even if I spent the whole night up sick or broke my hand and needed surgery three days before the trip. Despite or because of my willingness to slog through no matter the cost to myself, I was always a high performer.

However, at a certain point this way of being breaks. For me the tipping point was becoming a manager. Pushing to the breaking point didn’t work. In fact, the harder I pushed, the less it worked.

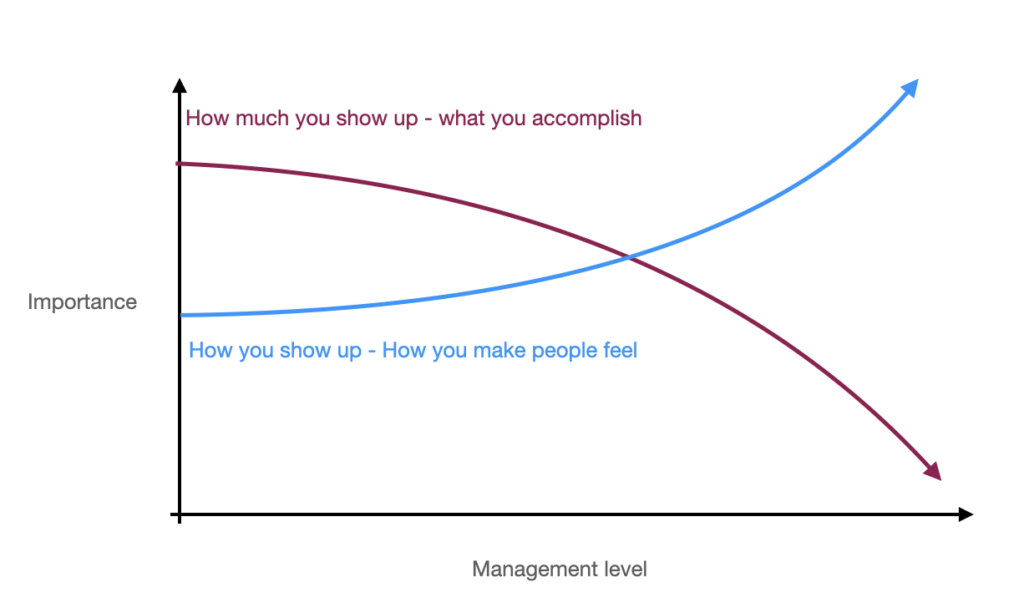

I could struggle through IC work and early parenthood, but I coudn’t struggle through managing with any success. Managing people through constant crisis is care work. My success (such as it is) rests on how well I can care for my team to get them through crisis after crisis, how well I can find people to help me navigate organizational structures optimized for capital generation, not human centered design. My role being entirely other-oriented has meant I need to rethink how I show up and how I prioritize caring for my self. We’ve all probably heard the cliches “you can’t pour from an empty cup” and “put on your oxygen mask before assisting others.” They both resonate in new ways as my role and my life as a parent transition from the need to just get things done, to a point where HOW I do things is as or more important than what I do.

I can’t be a good manager when I’m miserable and burned out. I know because I tried. I used the mantra “dump up and motivate down” in my prior role during season 1 of the pandemic to compartmentalize my exhaustion and frustration, trying to show up and advocate for my team and my colleagues, while simultaneously crying from frustration regularly because of the the projects I was managing and the frustration that I felt about MY impact, MY career opportunities, MY performance, and the constant crises that challenged my hope daily. I didn’t model good boundaries to my team, and the harder I pushed, the harder I was on myself and the more I let my expectations for personal accomplishment drive my choices, the worse I felt and the worse I did at work.

When I show up now, I need to show up as a calm guiding presence for my team, as a trustworthy partner for my cross-functional peers, and as a compelling advocate for the kinds of shifts needed to grow our design and research practice and influence. Managing is an other-oriented role, where success isn’t personal, but rather is a result of interdependence and relationships. What does achievement mean in this context? Achievement means enabling more than achieving. It means that, to put it bluntly, it is not about me. It is not about how smart I am or how much I personally can achieve. It is about how I make people feel. My success is in my ability to nurture and mentor my team. For me, this has required a gradual but radical shift in how I think about my work and how I manage my time and energy, as well as making intentional choices about how I want to advance my career so I can work with care and compassion as guiding forces.

A few things I’ve changed that made me a more effective compassionate leader:

- Letting go of control and delegating intentionally: giving the people on my team a chance to shine or learn through failure is usually more important long term than making sure something is done perfectly or the way I would do it.

- I show and tell my teams that caring for themselves and their families is more important than work.

- I let the news and the fullness of people’s experience into our work. If there is something rough happening in the world or with their lives, I try to make space to talk about it, problem-solve around it as needed, and provide cover and reassurance that it’s ok to take some time.

- I build moments of recognition and bonding into all of my team’s work. When partners help us (which is ALL THE TIME at any organization) we try to find ways to lift up their contribution to our work.

- I cancel things! A year ago I would have had my staff meeting the morning after the Supreme Court leak. Instead, I cancelled it so I could take extra time in the morning to read the news and process with my partner. This allowed me to show up calmly rather than tearfully. I sometimes have “conflicts” that are just not feeling like I can productively show up and I need a break. I will never try to work a full day after a night of food poisoning again (it’s a low bar, I know).

- I have been working on my emotional distance. Coming from academia every success or failure for years felt like a referendum on my personal worth. I’ve stopped seeing things that way most of the time. While I still stress about things like promotions and making projects successful sometimes, I spend more time trying to understand the aspects of the system affecting the outcome that have nothing to do with me, and that I might not be able to impact even if I tried (I generally try).

- I write these short articles. Since I don’t get to control everything about how work gets done on my team but I love research, thinking and writing, I have found these little articles are something that is mine outside of work that I can control.

- I place a much higher value on my mental and physical health than I ever have, even when it costs me time at work or with my children, time I felt in the past I owed to others.

Relationships are always important at work, but for people managers, relationships are the work. Navigating politics becomes a bigger and bigger part of the job the higher up in an organization you go, and people have more influence and ability to shape organizations and their values the higher up the ladder they climb. Hurt people hurt people, and I imagine many of us have had the misfortune of working with or for someone who’s version of success did not shift when they moved into management, staying focused on individual competition rather than creating meaningful relationships. This kind of “talented jerk” manager leaves a trail of bodies behind and below them. They create organizations that run on fear and reward short cuts, immoral behavior, externalizing costs, and winning above all — just what our society needs less of. Managing without compassion for oneself and others breaks people and teams at the best of times, and these are not the best of times. We can’t show up for each other like that these days and expect a good outcome on any level. The past couple of years have shown the centrality of care to our lives and careers, and if we have learned anything from the unchosen traumas over the past few years, I hope it is how interconnected and interdependent we all are on both individual and systemic levels. We can’t power through this, but if we show up with vulnerability and compassion we just might create systems at work and at home built on care and humanity. The alternative isn’t working.