If you’ve seen the Matrix trilogy, it’s hard to forget the scene where Neo jolts awake to find himself in a glowing red pod, covered in goo.

Naked and disoriented, he tries to reconcile what he thought was real — living as a regular guy in a regular city with a fairly regular life — with the horrific reality that his pod is surrounded by thousands of others, each housing a gooey, sleeping human. In a post-apocalyptic world controlled by machines, people have become fuel.

Unwittingly, Neo was feeding into a system that was destroying humanity and too consumed by the Matrix to notice.

Science fiction often sheds light on real-world scenarios, and we’re currently in a Neo-esque predicament: we’re fueling a climate crisis that will destroy humanity’s ability to live on this planet we call home, and we’re too connected to technology to notice.

For digital product makers, this has interesting implications.

When we think about combating climate change, recycling or biking to work comes to mind, but not the UX we design every day. After all, digital experiences and products don’t feel pollutive. Computers are sleek, self-contained, odorless, and gasless. And being online is individualistic; even when video conferencing, it’s still just you on the other side of the screen.

When we think about combating climate change, recycling or biking to work comes to mind, but not the UX we design every day… But if the internet were considered a country, it would be the 7th most polluting country on earth.

But if the internet were considered a country, it would be the 7th most polluting country on earth. The carbon footprint of our gadgets, the internet, and the systems supporting them are on par with greenhouse emissions from the airline industry — and are predicted to double by 2025.

As the people crafting the digital experiences requiring so much energy, we must rethink our methods and outcomes. Otherwise, we’re complicit.

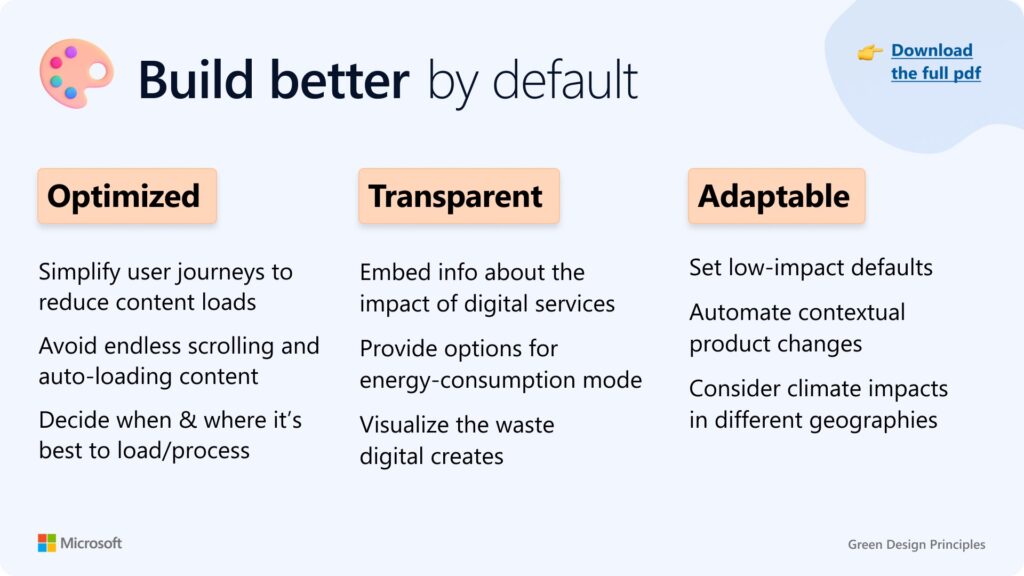

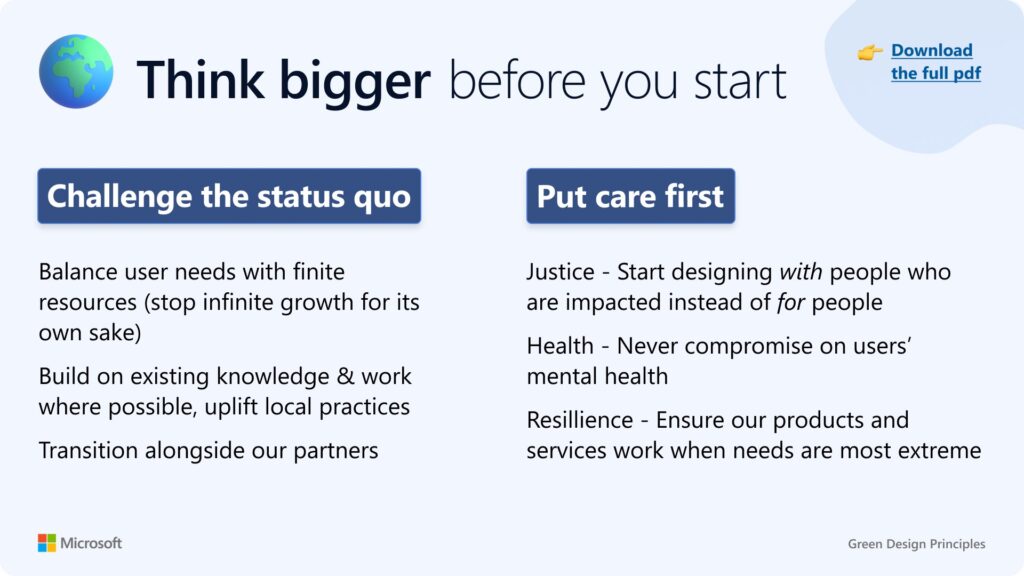

Microsoft has bold climate goals, and Microsoft Design does as well: to reconceptualize digital design to be more sustainable. Our recent Green Design Principles mark the beginning of a broader push to support product makers in using our creativity to design for the complexity of the climate crisis.

“The Cloud” doesn’t exist

Every product maker needs to drill into their practice that digital is physical. Every design has physical implications, from the amount of energy that it takes to power an experience to the real-world choices users make based on the information we present and the stories we tell.

Perhaps the best example of this is “the cloud,” one of the greatest diversions of the 21st century. While people were fancifully thinking that the massive amounts of data they create and utilize floated about in a beautiful ether, data warehouses aggressively expanded across the globe.

Real clouds are beautiful and organic. The cloud is a massive (and massively hot) warehouse filled with flashing lights, spinning discs, and cooling fans whirring in overdrive. It looks more like the scene Neo woke up in than a Bob Ross painting.

Every design has physical implications, from the amount of energy that it takes to power an experience to the real-world choices users make based on the information we present and the stories we tell.

These warehouses consume an immense amount of energy, and that’s only considering computer software and web experiences. When you add devices into the mix and technologies like blockchain or NFTs, the energy requirements become even less sustainable. Bitcoin and Ethereum — the world’s two biggest blockchains — use the same amount of electricity as the entire country of Austria. And hybrid work, often touted as being more environmentally friendly because you don’t commute, is potentially even worse for the environment because workplace energy needs remain high and home energy use increases.

Given how central coal and fossil fuels are to the energetic supply chain, the most cloud-like aspect of computing is the black smoke billowing from the factories that ultimately fuel it.

The unintended consequences of well-intentioned designs

The job of all product makers is to consciously construct. Creating solutions to wicked problems and practicing “design thinking” is often a process of becoming aware. Aware of user pain points. Aware of existing solutions and how we might elegantly evolve them. And — in theory — aware of our solutions’ impacts once we release them into the world.

Bad design often results from a failure to account for the invisible. Unconscious bias, historic contexts, power dynamics — we typically only see the aftermath of these invisible forces. Apps designed to connect us now lead to quiet family dinners with people glued to their phones. Highways built to bridge cities instead divide longstanding communities. AI intended to improve people’s lives instead promotes sexist hiring practices or racial profiling.

Bad design often results from a failure to account for the invisible…We need better ways to visualize our impact, such as tools that quantify the CO2 output of an app or models that show the cumulative effect of cloud services on small farming villages.

This same invisibility is part of what’s hindered sustainable design. Polluted water, blackened skies, draught, shortened life spans — affluent, western product makers tend to be shielded from the climate crisis our designs directly contribute to. We need better ways to visualize our impact, such as tools that quantify the CO2 output of an app or models that show the cumulative effect of cloud services on small farming villages. We’re otherwise likely to perpetuate a cycle where those living in poverty feel the brunt of our design’s negative impacts.

Industry advancement shouldn’t need to come at the cost of those less fortunate. While the coal industry grew rich, the people of Appalachia — already one of the most impoverished regions in the United States — had their farms ruined and water supply polluted thanks to the use of explosives during mining. And in the U.S. and Europe alike, an ever-growing racial wealth gap creates a double whammy for communities of color. The most affordable neighborhoods often have the worst air quality (68% of Black Americans live within 30 miles of a coal-firing power plant), which impairs people’s health and shortens lives.

One of the best antidotes to these blind spots is representation and intersectionality, both of which are fueling a growing Climate Justice movement. Within Design, we’re often taught to consider how a single element contributes to a more complex digital ecosystem.

Intersectionality within sustainable design asks that we take that same idea — designing for an ideal interrelation between elements — and widen the lens to include the communities, systems, and environments within which our designs live. And intersectional solutions are ones whereby addressing one issue (like climate change) you can address others (like race or class disparities) and vice versa.

This is one critical reason why representation in tech matters. People who live in the communities most adversely affected by climate change should be helping lead the ideation of new designs. There’s a wealth of perspectives and frameworks that tech hasn’t broadly considered or adopted — and it’s critical that we change this if we hope to minimize the unintended consequences of well-intentioned designs.

Solutions & Ideas: Train AI to love and preserve the planet

Oftentimes, the more complex and the less visible a system is, the harder it is for us to understand and change. We aren’t a single hive mind that can see everything, and that makes it challenging to ladder our individual actions up to a bigger system. Part of Ray Kurzweil’s belief in the singularity is that he’s looking at the power and limitations of humans and tech alike and imagining them merging in a way that leverages the best of both.

AI’s superpower is that it can see and interconnect everything — so let’s employ the energy-intensive cloud and the AI it enables to understand environmental impacts.

Even better, when designing AI, we should hire and consult with Indigenous peoples. For centuries, Indigenous cultures worldwide have operated within ecological frameworks that respect the delicate nature of interrelationship, and there’s an important push to weave Indigenous knowledge systems into the development of AI.

Designers can be more deliberate about how much data we decide to collect, and we can embrace sustainable default settings, such as automatically turning off video when someone isn’t speaking, or using Dark Mode.

Beyond thinking algorithmically, there are many ways that designers can make a notable difference. We can be more deliberate about how much data we decide to collect, and we can embrace sustainable default settings, such as automatically turning off video when someone isn’t speaking, or using Dark Mode, which uses less energy than Light Mode on an OLED display. We should also explore more carbon-aware digital experiences and take inspiration from solar-powered websites or server structures.

Sustainable UX also creates more frictionless user experiences. By designing within the constraints of energy efficiency, we can improve user focus and increase accessibility. For example, pages that use less data load far faster, and designs that are easy to read and navigate mean less time spent online.

The red pill or the blue pill

From the moment you acknowledge that the cloud doesn’t exist and understand the degree to which digital equals physical, you’ve taken the red pill.

Neo woke up to the reality of the Matrix because he chose to. Neo’s life had been great in many ways, but something felt off. So, Morpheus gave him a choice between a blue pill that would ensure reality as he knows it stayed the same, or a red pill that revealed the truth. He chose red, and only then could he create meaningful change for humanity.

Some of the most engrained paradigms of the tech industry are the least sustainable…product makers need new ways of working.

Today, some of the most engrained paradigms of the tech industry are the least sustainable: a need for speed, building new technologies instead of optimizing existing ones, and capturing and storing data like there’s no tomorrow. Product makers need new ways of working — new design tenets, frameworks, and principles — or we’re choosing the blue pill and being complicit in the climate crisis. It’s that simple.

And while no guide quite compares to Morpheus, our teams have put much research, craft, and heart into the Green Design Principles. We sincerely hope they’ll help you begin your green design journey, and we welcome any feedback you might want to share!

The Green Design Principles were created by an amazing group of people who came together worldwide to further the art of designing for sustainable futures. Abigail Cawley, Aditi Khazanchi, Anna Alfut, Caitlin Esworthy Greene, Chelsea Braun, Connie Huang, Danielle McClune, Emily Lynam, Janka Koen, Jen Hofer, Jennifer Bost, Martyn Gooding, Pragya Gupta, Rachel Bergman, Ryan Hayen, Sandra Pallier, Sarah Shing, Shane Tierney, Shelley Bjornstad, Soumitri Vadali, and Sue Nguyen — thank you SO much for your craft and commitment!!