Save

In July 2016, I joined Uber as the first member of our Bangalore-based UX team. I was one of the earliest researchers at the company outside of the U.S., and at that point, the Bangalore office had just opened and things were still taking shape. It seemed overwhelming at first — being in a distributed office, not having any other UX team members in the office, and working with a lot of non-technical teams which were new to UX research. However, this setting gave me a lot of opportunity and autonomy. This was a company that was extremely fast, exceedingly innovative, and deeply caring of its users.

I got the opportunity to work on various teams, conduct research internationally and work with brilliant cross functional teams. I started as a researcher on a team called India Growth which focused on building our business specifically for the India market. I later moved to the Rider Access team which aimed to make Uber more accessible to riders in emerging markets via modes other than the rider app. In September 2018, I moved to Uber’s office in San Francisco as a researcher for Uber Eats , focusing on the trip experience for delivery people. And now I lead research across all verticals for delivery people on Uber Eats globally. I had the opportunity to conduct research in countries like India, the United States, Brazil, Singapore, Costa Rica, Ukraine, Mexico, Spain, France and the U.K. I worked with exceptionally smart people in different functions across product management, data science, design, engineering, product marketing, and on-the-ground operations, to name just a few.

As I sit and reflect on my 3.5 years at Uber, I feel grateful and amazed by how much I’ve learned and grown in this role. Today, I want to share ten important lessons I’ve learned while working as a UX researcher for the company. My hope is that my learnings can be applied to your own work, and that you’ll share your thoughts and experiences too. I’d love to start a dialogue that could contribute meaningfully to the growing field of UX research!

1. Think Globally

This may seem like an obvious one, but my belief in this has increasingly strengthened with each project. Addressing cultural and regional differences is incredibly important. After having worked at a global company like Uber — whose app is used by people across hundreds of cities, cultures, and backgrounds — one becomes very cognizant of the fact that one solution doesn’t fit all. For example, what works for a driver in the U.S. might not work for a driver in India. There are considerable differences, and accounting for those differences right from the very beginning makes for a better product experience.

One of my favorite examples of this lives within the earnings tracker of the Driver app. This feature shows drivers a running tally of their daily earnings. As we conducted research across markets, we found that, while drivers in the U.S. loved the feature, many drivers in Saudi Arabia felt it might bring bad luck and due to safety reasons, drivers in Sao Paulo preferred to not have this feature at all. Thanks to our research, we decided to launch this feature with a toggle to activate or deactivate visibility. This seemingly minor tweak helped improve the earnings experience for thousands of drivers.

Understanding cultural nuances is critical. One can start by working with local operations teams and data science teams to find out how markets vary in different aspects and then plan research to cover all critically different and strategic markets. If you don’t have those resources, even referring to some literature on how cultures and geographies differ can help in figuring out strategic markets for research.

2. Assess and prioritize

Try to ensure that the research you are doing is worth the effort and brings sizable product and business impact. Given that UX research is still a relatively young field, not everyone understands it well. This means your cross-functional partners might not always understand how to best use UX research or what questions to ask of researchers. Therefore, it becomes even more crucial to assess whether the research questions you are pursuing are the most valuable and impactful for the team and users.

Educate your stakeholders as to the kinds of questions UX research can best answer and also to its limitations. Ask them what they expect from this research and help them evaluate if those are the right questions to ask. Assess if they are being too narrow in focus or too broad in scope. Assess whether UX research is even the best way to answer certain questions or if they might be better answered by other means. Consider whether you need to spin off a new project for these questions, or if they can be answered by reviewing the existing literature. And finally, ask the team to articulate the impact of not doing the research — this makes them think about research more deeply and helps when prioritizing projects.

3. Get out there

Nothing, absolutely nothing, can replace getting into the user’s context (i.e interviewing/observing them in their natural environment or the real environment where they will use a product). Throughout my time at Uber, I have done research in-lab, remotely, and in the user’s context. Without a doubt, what stood out to me was the experience of learning from users in context. There are so many nuanced details one misses when interviewing users out of context or testing products where they are not intended to be used. One of the ways we do research in context with delivery people is by riding along with them when they deliver food. This helps us learn how they are interacting with the app in a real-world setting in real-life conditions.

4. Get creative with your methods

In my early months at Uber, I would often hear the phrase ‘creative research methods’ and, at first, I wasn’t quite sure what that was supposed to mean. I soon found, however, that it encompassed a wide variety of techniques that involved improvisation and flexibility, lateral thinking, and a can-do spirit. My favorite example of this happened on a research trip to India when my team was trying to figure out how to get 14 cross-functional members (from design, research, product, operations, marketing) from San Francisco — none of whom knew the country, culture or local languages other than English very well — to understand the experience of motorbike delivery people in New Delhi and Hyderabad.

After a lot of brainstorming, we decided to conduct ride-alongs in a somewhat unusual way. We split the contingent into three groups, each of which rode in a car that followed a bilingual researcher who sat behind a delivery person on a motorbike. Each team was composed of:

1 delivery person

+ 1 researcher (as pillion rider)

+ 1 carload of observers (4–5 per car)

= 1 solid example of “creative research methods” at work

The motorbike and car were connected to each other via video call or voice call. It was a brand-new way of doing ride-alongs!

The researcher would regularly report to the team in the car (read: provide live translations from Hindi to English) what they saw or heard from the delivery person while on a motorbike. From the car, the team could observe what was happening and ask the delivery person questions via the researcher. When the delivery person went to pick up food from a restaurant or to drop off food for a customer, the team could observe the entire experience. Needless to say, the delivery people we recruited for this study signed up voluntarily and were compensated for their participation in our study.

Coming up with this method took time. We needed to capture the trip experience of delivery people in certain specific situations and we needed to see how they behaved in that context. We knew that no traditional method would fit the situation and that we needed to get creative.

Now, in many situations traditional methods will work just fine, but it’s worth considering if there is something that you can add to this traditional method to capture some more interesting data points that will make your insights stronger or uncover nuances that might otherwise be missed. In situations where traditional methods don’t work, push yourself to think about how to function within constraints and how you would put together an entirely new method. However, remember to be mindful of and vocal about the pros/cons and potential constraints/biases of any new method.

5. Bring stakeholders into the field

“I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand”. — Confucius

When I think back to my research projects, I find a clear difference in the level of agency and motivation that stakeholders had when they’d experienced or seen a user problem first hand versus when they’d just read about it in a slide deck. By taking cross-functional team members (product managers, engineers, designers, data scientists, etc.) into the field, not only do we help generate empathy for users, we also build deeper appreciation for and better understanding of the methods and processes researchers use. My team and I always end up coming back from the field inspired to collaborate and make changes together.

Before taking everyone out to the field, make sure to give them some preparation. Trainings before field trips help stakeholders understand what to expect. These trainings can include instructions on how to prepare for research sessions as well as guidance on how to take notes, photos, and videos during sessions, tips on moderating sessions, and how to make the most of your research post-field trip. This makes team members feel more confident and better prepared to handle field days.

6. Experiment with new methods of sharing insights

Most research reports end in traditional slide decks/documents, but there is value in exploring other ways of sharing insights. While slide decks offer a consolidated view of all findings, they are also time-consuming to put together, and some situations could benefit from more real-time share-outs.

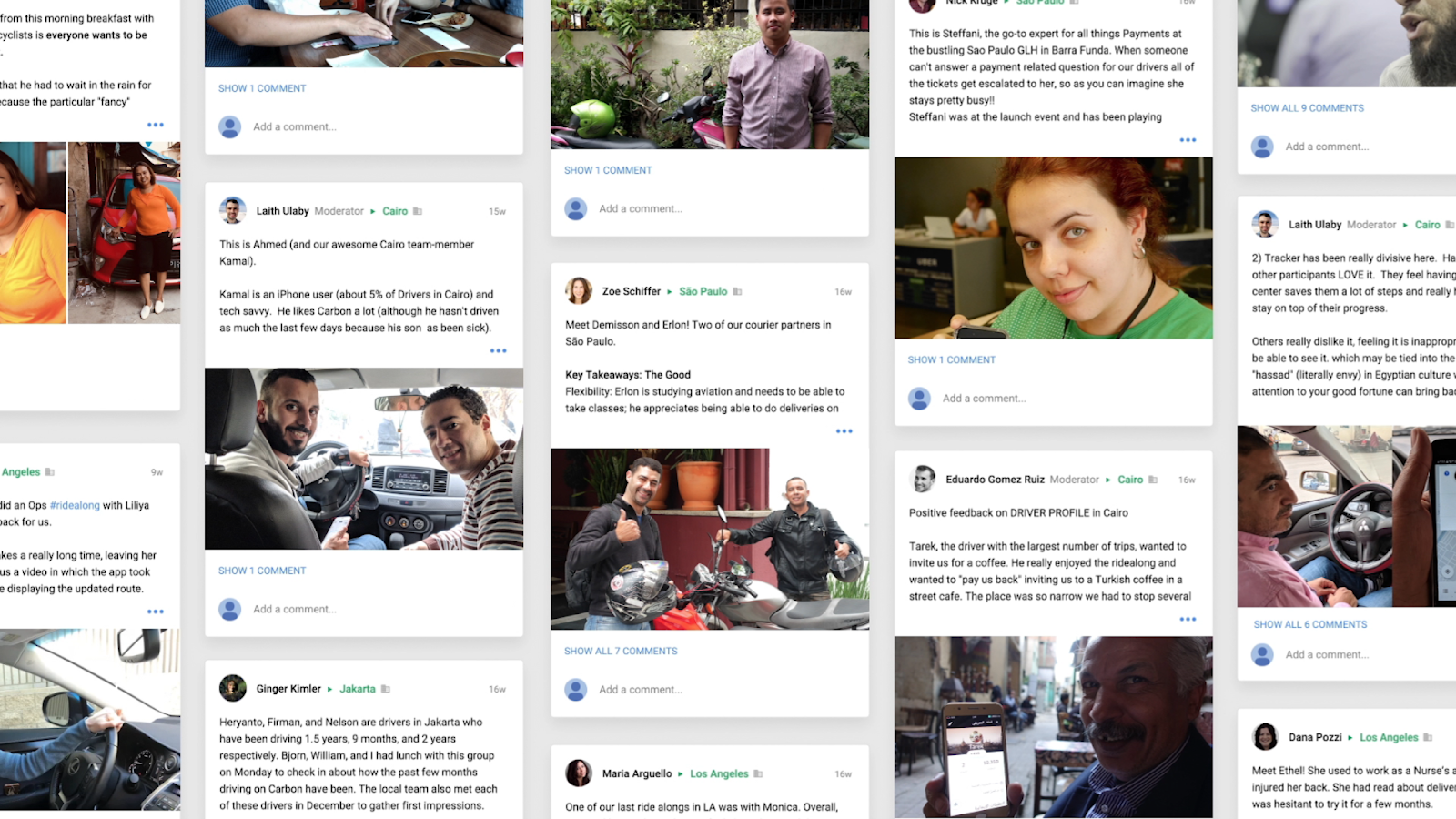

For the global beta of the Uber Driver app, we conducted a three-week-long research sprint in six cities globally. This was a large effort affecting about 3 million drivers across the world and the majority of the product development team was based in San Francisco. We did not want this beta research to be like a traditional research project where researchers conduct studies in a remote market with a small team, then communicate findings back to the larger team in a couple of weeks. We wanted the team to feel closer to the users in all possible aspects. We believed that would create more empathy, provide more agency and hence make the team more invested in the findings and prompt quick action. To enable this, we experimented with posting bite-sized unsynthesized pieces of data (which we later called “atomic evidence”) right after a research session on a G+ group. This was an internal G+ group that included all cross-functional tech and operations teams that were involved in the development and launch of the beta app. Through this, stakeholders were able to see feedback from a driver in Bangalore or Jakarta, for example, not days later, but minutes or hours after we did a ride-along.

We were surprised to see that our research went viral within the company! Stakeholders were highly engaged and quickly started workstreams right on G+. This prompt response in turn motivated researchers to surface more meaningful stories. The drivers who we were conducting the research with, were able to learn about the progress through the researchers and could even see some of the changes made to the beta app during our study. We were eventually able to see quick impact along with a positive sentiment from app users and internal stakeholders alike. We attributed a large part of the success of this research project to this novel method of sharing-out.

7. Collaborate cross-functionally

You can’t and won’t be able to do everything. You will be an expert at certain research skills and there will be others on the team who have mastered complementary skills. Collaborate with them. There is so much wealth that one ends up uncovering when working with cross-functional partners like data scientists, marketing researchers, and product marketing managers.

Capitalize on these different functions and skill sets. For example, when you see an unusual, unique or important user behavior in the field, ask a data scientist to see if this is a common behavior based on log data. Try to map your learnings with what the customer support team notices in support tickets. Try to work with cross-regional teams to see how user behavior is similar or different in different regions.

8. Expect the unexpected

There will always be surprises in the field. Keep calm and continue researching. Before each of my field research trips, I make long and extensive checklists. I make sure that all the participating cross-functional teammates and external vendors (if involved) are on the same page, and ensure that all equipment is charged the night before. But despite all this planning, when I am in the field, countless things can go wrong — mobile networks fail and you can’t contact stakeholders, your note-taker calls in sick, traffic delays your interview by 30 minutes, your voice recorder runs out of batteries., the list goes on and on.

These situations can happen to anyone. The key is to keep calm, be patient, and be flexible. Forgive yourself quickly and try to make use of the available resources in that moment. I like to build in buffer-time between sessions and use that time to figure out a plan B if needed. Always account for traffic unpredictability, have a list of back-up participants that can be contacted in case of dropouts, and have most of your research resources (interview guides, artifacts) available offline or on paper. And most importantly, know that there is only so much you can control, so take things in stride.

9. Reflect, recover…and then act

Research can be overwhelming. Participants are opening up their lives to you, and even when it is uplifting, it can be emotionally draining to learn about people’s lives, about their hopes, fears and dreams. Take time to soak it all in; take time to reflect on it.

Don’t cram too much in one day — I try to give myself enough time between sessions to debrief with others and to think on what I’ve learned. At the same time, know that when you are getting to know someone’s personal stories — how they live, how they earn money, how they take care of their families — this disclosure comes with a responsibility. Take stewardship of what you learn. Be protective of and accountable to your users’ wants and needs. Be their voice. Be loud and persistent. That is what makes our lives as researchers enriching and fulfilling.

10. Never “I”, always “we”

This is something I first learned from my professor at design school (Department of Design, IIT Guwahati) and it’s been constantly reinforced over my last three and a half years at Uber. Whenever describing research, I never use the word “I”. There are so many people who contribute directly or indirectly to a project, and I find it almost arrogant to talk about any project using “I” even if I am leading it.

It takes a village to get a research project done. Product managers and designers help decide most important research questions. Data scientists help pull data to build hypotheses around research questions. Research operations experts help recruit participants. Cross-functional teams join as notetakers and observers. On-ground operations teams help set up local logistics…these are just a few of the many people who get involved. I make it a point to acknowledge their efforts and contributions. Every project is “our” project. A simple change in pronoun more accurately reflects all the work behind-the-scenes, and provides a more inclusive and encouraging sentiment for everyone on the team.

Over the last three and a half years at Uber, I find myself incredibly lucky to have had a job that’s enabled me to be a part of so many lives across the globe. I am grateful to our users for sharing their lives and their stories, and am humbled and inspired by the opportunity to impact those lives and those stories in a meaningful way. This has been a truly rewarding journey. As Uber moves into new products and verticals and further matures as a company, I am excited to see what new opportunities arise for research and curious to explore how our tactics and methods will change.

So: that’s my story. What’s yours? Whether you’re a research vet, a newbie, or just the bearer of a curious mind, I’d love to hear your story! Feel free to comment here or email me at [email protected]

Minal works as a Sr. User Experience Researcher at Uber in San Francisco. She leads research globally for delivery people using Uber Eats. She started with Uber 3.5 years ago, where she focused on growth of Uber in India and later moved on to exploring the question of how Uber can be made accessible to riders in all emerging markets.

She has an educational background in design and has worked with companies like Samsung and IBM Research in the past.