Save

While I naturally ask myself many questions around ‘What design is today’ and ‘The impact of design thinking for businesses and design’, these must of course be considered hand-in-hand with ‘Who and what is the designer of today*?’ … not in a philosophical sense, but I am keen to consider and investigate the particular dimensions and characteristics that different designers possess and how they vary across genres.

*So as not to confuse, I’ll set the control volume of my discussion to be designers that are more in the digital and strategic realm as opposed to those that work in more established and craft orientated design fields. Equally I am not including those people that are just/only ‘human-centred thinkers’ (at the other end), but I will be using them both as reference points.

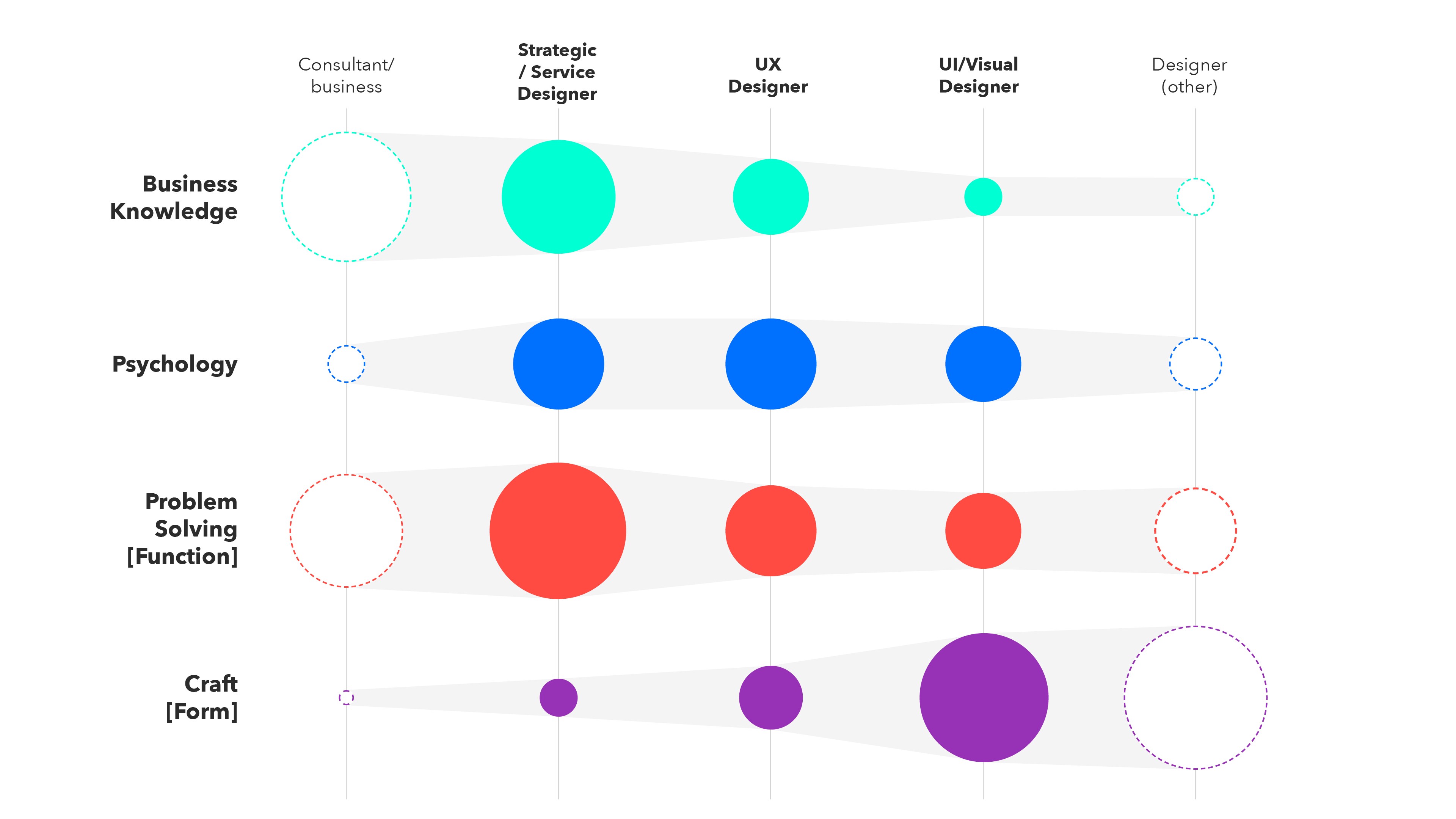

The anatomy of a diagram

I’ve taken and simplified (all design and) designers to embody 4 key capability traits:

- Business understanding– in terms of knowledge around business, strategic design applied to business, design thinking, and holistic human centred problem solving.

- Psychology– the ability to understand and empathise with humans. To look at ergonomics (cognitive) and create solutions that are driven by and align with human behaviour and emotion.

- Problem Solving [Function] — the ability to create and structure a product or process so as to deliver a desired outcome to the problem or question set. Normally a manifestation of a methodological approach to change inputs into desired outputs.

- Craft [Form]– the ability to create physical and visual artefacts with a comprehension (and perhaps mastery) of colour, contrast, type, feature, shape, balance, material and manufacture.

These dimensions whilst different, are not necessarily orthogonal — in that e.g. Psychology of course does entail some degree problem solving. I am just seeing /positioning them each as unique enough from the others to be a discrete skill.

Here I have illustrated, purely at a relative level (not based off any numerical data), but on the encounters I have had with many, many designers — from working with them to interviewing them, the relative magnitude of each of these capability traits. [Readers, I appreciate these may be slightly different in your book, but I hope the logic and flow hold true]

i) We see that strategic designers (e.g. service designers) have (or at least need to have) a much greater understanding of business. The particularly good ones have a psychology affinity also, as driving business solutions through a human centred approach means really appreciating the people in the ecosystem. If they did not, they would be much more like business analysts and business process engineers. Many (but not all) strategic designers do not have craft abilities, and many of them do not come from design backgrounds. This leads to the question, is what they do design? and, are they designers? (But that’s a whole other blog: see Dangerous Times in Design)

ii) UX designers may not have as much business knowledge and understanding (although of course, having it is beneficial). The psychology now needed is of a slightly different flavour and really considers expectations and aspirations around interactions (as is the problem solving). UX designers can (and do have craft) although it is not necessarily a given.

iii) UI designers are much more based in the craft of design; however, it would be wrong to say that they do not possess strong problem solving and psychological abilities — they just have very different flavours of these criteria. It becomes the psychology around perception and affordance and problem solving at moments, rather than at a holistic level. Now, we consider this to be ‘Design’ very easily/happily, but should the definition of a Designer now suggest that even UI designers, need to have a much broader capability such that they can be considered ‘modern’ designers?

… while the remit was to consider the main professions in ‘new’ design, it is interesting to look either side also…

· Consultants (managment or otherwise) and people within business that have the title or the capability of ‘Design Thinking’, and those that more generally adopt a human centred approach to problem solving (see my other blog: ‘Design thinking isn’t Design, its Design Thinking’.) Now we should draw the line somewhere, so I would say that these people are not designers, but of course they do (or automatically will) encompass some of the characteristics highlighted here. We could (and perhaps should) start asking the question ‘how much’ of each dimension does there need to be ( i.e. how big do the circle in the diagram need have to be) before we do say they are designers?

· Designers from the established fields; let’s take this to be the likes of product, fashion, interior, automotive etc. It is inaccurate to label them all under one umbrella as such — the nuance lost is great, but what this column shows is the greater extension of the dimensions’ trend. [NB it is not to say that these designers are not strategic, but just that their design process is not the director of their business product]

Practically, this diagram is there just to illustrate that these dimensions do changes across different design disciplines.

Design and designers have evolved in new directions and what was once easy to pigeon hole, now certainly isn’t. The question to ponder is how much of each (dimension) qualifies someone as a designer, and which sort?

I like to keep my blogs real world and practical — So where is this dissection going?

The modern-day designer is a complicated being.

Designers now are more complex, with more fundamentally different skills and expectations than ever before. With the likes of design thinking, service design and digital design ‘stretching’ the remit of what is considered ‘design’, the building blocks of designers too has diversified.

This makes trying to judge what is good design and who is a ‘good’ (it is subjective, although I have always thought there are some objective components within it) designer, ever more difficult. This result of this I have seen manifested in how enterprises and consultancies are choosing to hire design talent both for their permanent teams and as contractors.

Design is fluid enough that just by a person having the appropriate design label (of e.g. UX designer), it does not instantly make them above a certain quality threshold. (It is unlike medicine or law, whereby only after a certain education, qualification, performance and experience can you call yourself that profession). In theory anyone can ‘call’ themselves a designer… so how else have I seen people decipher?

Brand names. I believe that sometimes more corporate/commercial people hire designers based on where they have worked before. This does of course make sense at one level, but, by default, relies on the fact that the previous ‘big brand’ has judged well. That the past employer who may hold great kudos in the marketplace or even enterprise prestige, is somehow consistent with their ability to be a great judge on what makes good design and a good designer. Dangerous.

(Arguably) one of the best ways to judge, is for another trusted, professional designer, to evaluate that potential new hire. Only someone from the field, who has done, or at least seen ‘good’ design would be better placed to judge. Not that it should be this person’s decision only — the original hiring person would after all be much better placed to see if the new person is right for the team, department and business overall.

Design and Designers are in a difficult and exciting time. New designers have great opportunities to be in places of influence in businesses (and governments) in a way more than traditional designers ever had, but equally, corporation’s inability to judge designers who are put in these places of responsibility have the potential to damage the industry as a whole.

Anish is currently Head of Design & Innovation for Shell where he is helping to create, from the ground up, a new worldwide digital innovation lab capability that sets out to develop products and services through design, lean innovation and agile methodologies, coupled with new technologies. He champions a holistic human centred proposition from design thinking and service design, through to digital creation (UX & UI); leading, managing and creating, strategic, digital and physical work, blended with a solid business understanding that pushes beyond current trends into future focused innovation.

Anish has an Executive MBA at Imperial college London where he has also explored how strategic design can combine with business in original ways.