Information is not a fad. It wasn’t even invented in the information age. As a concept, information is old as language and collaboration is. The most important thing I can teach you about information is that it isn’t a thing. It’s subjective, not objective. It’s whatever a user interprets from the arrangement or sequence of things they encounter.

For example, imagine you’re looking into a bakery case. There’s one plate overflowing with oatmeal raisin cookies and another plate with a single double-chocolate chip cookie. Would you bet me a cookie that there used to be more double-chocolate chip cookies on that plate? Most people would take me up on this bet. Why? Because everything they already know tells them that there were probably more cookies on that plate.

The belief or non-belief that there were other cookies on that plate is the information each viewer interprets from the way the cookies were arranged. When we rearrange the cookies with the intent to change how people interpret them, we’re architecting information.

While we can arrange things with the intent to communicate certain information, we can’t actually make information. Our users do that for us.

Information is Not Data or Content

Data is facts, observations, and questions about something. Content can be cookies, words, documents, images, videos, or whatever you’re arranging or sequencing. The difference between information, data, and content is tricky, but the important point is that the absence of content or data can be just as informing as the presence.

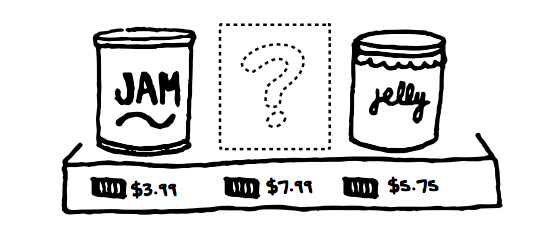

For example, if we ask two people why there is an empty spot on a grocery store shelf, one person might interpret the spot to mean that a product is sold-out, and the other might interpret it as being popular.

The jars, the jam, the price tags, and the shelf are the content. The detailed observations each person makes about these things are data. What each person encountering that shelf believes to be true about the empty spot is the information.

Information is Architected to Serve Different Needs

If you rip out the content from your favorite book and throw the words on the floor, the resulting pile is not your favorite book.

If you define each word from your favorite book and organize the definitions alphabetically, you would have a dictionary, not your favorite book.

If you arrange each word from your favorite book by gathering similarly defined words, you have a thesaurus, not your favorite book.

Neither the dictionary nor the thesaurus is anything like your favorite book, because both the architecture and the content determine how you interpret and use the resulting information.

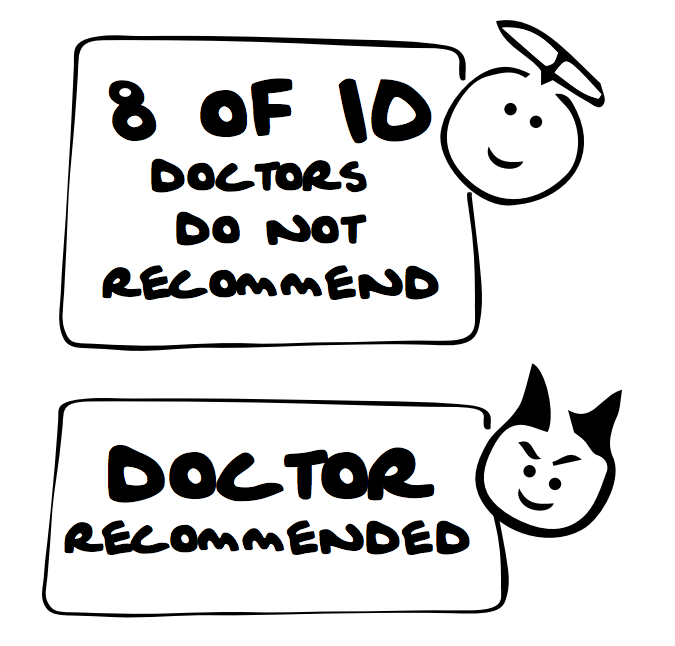

For example, “8 of 10 Doctors Do Not Recommend” and “Doctor Recommended” are both true statements, but each serves a different intent.

Users Are Complex

User is another word for a person. But when we use that word to describe someone else, we’re likely implying that they’re using the thing we’re making. It could be a website, a product or service, a grocery store, a museum exhibit, or anything else people interact with.

When it comes to our use and interpretation of things, people are complex creatures.

We’re full of contradictions. We’re known to exhibit strange behaviors. From how we use mobile phones to how we traverse grocery stores, none of us are exactly the same. We don’t know why we do what we do. We don’t really know why we like what we like, but we do know it when we see it. We’re fickle.

When it comes to our use and interpretation of things, people are complex creatures

We expect things to be digital, but also, in many cases, physical. We want things to feel auto-magic while retaining a human touch. We want to be safe, but not spied on. We use words at our whim.

Most importantly perhaps, we realize that for the first time ever, we have easy access to other people’s experiences to help us decide if something is worth experiencing at all.

Stakeholders Are Complex

A stakeholder is someone who has a viable and legitimate interest in the work you’re doing. Our stakeholders can be partners in business, life, or both. Managers, clients, coworkers, spouses, family members, and peers are common stakeholders.

Sometimes we choose our stakeholders; other times, we don’t have that luxury. Either way, understanding our stakeholders is crucial to our success. When we work against each other, progress comes to a halt. Working together is difficult when stakeholders see the world differently than we do.

But we should expect opinions and personal preferences to affect our progress. It’s only human to consider options and alternatives when we’re faced with decisions.

Most of the time, there is no right or wrong way to make sense of a mess. Instead, there are many ways to choose from. Sometimes we have to be the one without opinions and preferences so we can weigh all the options and find the best way forward for everyone involved.

To Do is to Know

Knowing is not enough. Knowing too much can encourage us to procrastinate. There’s a certain point when continuing to know at the expense of doing allows the mess to grow further.

Practicing information architecture means exhibiting the courage to push past the edges of your current reality. It means asking questions that inspire change. It takes honesty and confidence in other people.

Sometimes, we have to move forward knowing that other people tried to make sense of this mess and failed. We may need to shine the light brighter or longer than they did. Perhaps now is a better time. We may know the outcomes of their fate, but we don’t know our own yet. We can’t until we try.

What if turning on the light reveals that the room is full of scary trolls? What if the light reveals the room is actually empty? Worse yet, what if turning on the light makes us realize we’ve been living in darkness?

The truth is that these are all potential realities, and understanding that is part of the journey. The only way to know what happens next is to do it.

To read more about putting information architecutre to good use in a world that’s growing increasingly complex, pick up a copy of How to Make Sense of Any Mess. In it, Abby Covert shares a seven step process for making sense of any mess, preparing you to join an army of sensemakers who will tackle the information-based challenges that lay ahead.

Image of double-chocolate chip cookie courtesy Shutterstock.