The world’s most popular touchscreen tablet, the iPad, is predicted to sell 13.8 million units by 2010 and nearly 40 million in 2011.[*] Google, Dell, HP, Samsung, Windows, and ASUS all report that they have tablet devices coming out in the next two years. Just as touchscreen smartphones have done in the past few years, tablets offer new opportunities in productivity, entertainment, social networking, healthcare, and a host of other domains. Tablets also give new life to existing media. Specifically, there has been an unexpected resurgence in the interactive book. The Alice for the iPad interactive book, for example, has had such an impact that its creator, Chris Stevens, has been invited to appear on talk shows.

I have spent the last year driving design efforts for interactive books on touchscreen tablets and have learned a number of key lessons.

Lesson #1: Know Your Content

UX professionals often have an irrepressible impulse to organize concepts into taxonomies—probably to be expected from a professional group that spends half its time doing information architecture. However, interactive books, as repositories of content, are not easily categorized either as books, games, or information sources. Classifications such as fiction or non-fiction don’t really help either. Interactive books can be either non-fiction or fiction. They can be open-ended, or have a defined narrative.

When designing interactive books, it’s more important to know what the book is meant to achieve than it is to try to figure out what predefined category it might fit into. What an interactive book is meant to achieve strongly affects how its content should be delivered. A linear, fictional narrative will need navigation and interactions that help drive the story forward and ensure the reader doesn’t get derailed or lost within a specific interaction. On the other hand, a chapter-style non-fiction interactive book that covers numerous topics needs robust cross-topic navigation to allow readers to sample, search, and browse the book’s various subjects.

It’s crucial to know from the outset of an interactive book design process what content will fill the interactive book. Once the design moves beyond the earliest “back-of-the-napkin” concepts, the lorem ipsum filler text should be replaced with actual content. Storyboards and prototypes should use draft storylines from the very beginning.

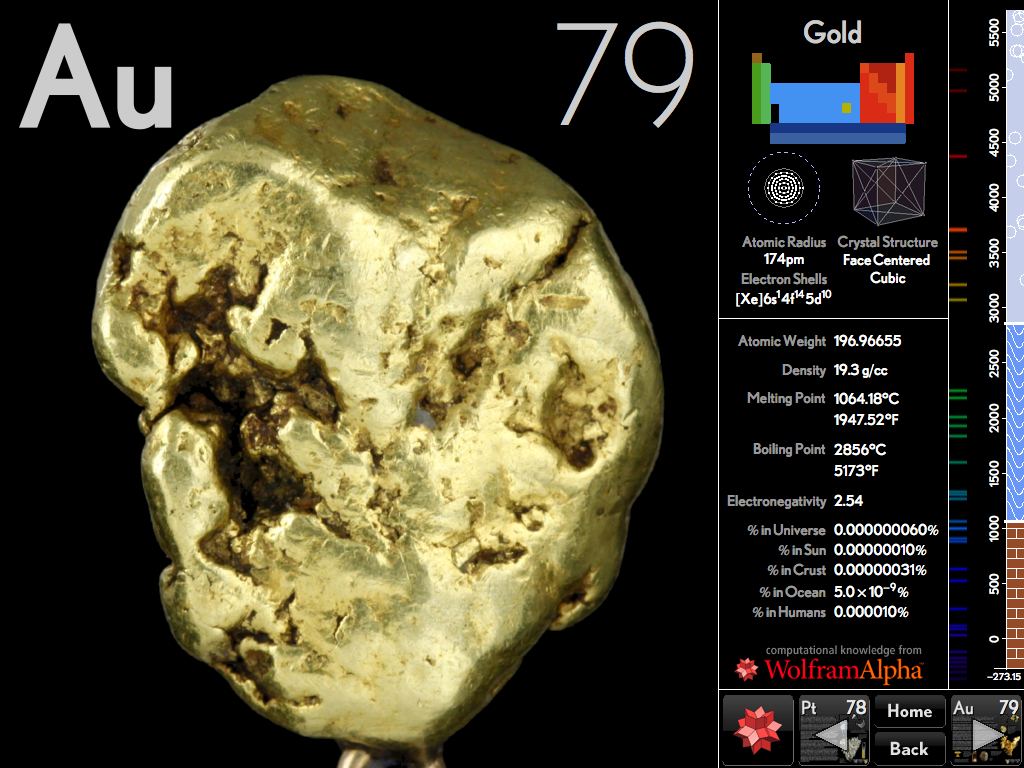

It’s important to note that interactive books have more than words, text, and data. Interactive books give the opportunity to fuse words, text, animation, and interaction. One of the popular early interactive books was built specifically around wonderfully photographed 360-degree animations of physical elements. The images communicate in a way that smaller pictures never could. Just as it is essential to use the actual story as early as possible, the visual media should be part of the design process as early as possible.

To summarize Lesson #1: Users will have a different experience with books that have a linear narrative than they will with ones meant for lateral exploration. The goal of an interactive book defines the content, and the content guides how much freedom a reader should have. Is the author attempting to tell a specific story, or will she allow many different stories to take place based on a reader’s choices? Or, is the author trying to impart a range of topics or vignettes? Each of these types of content will change the way the interaction occurs over time. Furthermore, it is important to look beyond words and consider the images, animations, and effects that make up an interactive book.

Lesson #2: Contextual Design

Interactive books have interesting physical, social, environmental, and technological contexts. It is essential to occasionally step back from a focus on interface design and explore the contextual factors that surround the interface. A tablet is a mobile, touchscreen device. This alone ensures it will be used in a much wider variety of contexts than desktop computers, which are generally chained to desks because of their weight and size.

Context considerations for interactive book design group into several categories:

Physical

Fingers are not mice. A fingertip is much larger than the fine point of a mouse cursor. Elements must be large enough to touch, but small enough to fit into a constrained screen size.

Arm strength is finite. When designing interactions for a touchscreen, arm strength has to be factored into the design, as arm strength is finite. On a regular computer, a user can work for hours through a non-stop series of keyboard and mouse interactions. With a tablet, the arm is not guaranteed a resting position on the desk or the arm of a chair. Either users develop arms like body builders, or interactions need to be broken up into chunks with resting phases.

Social

Computing together. A tablet device presents no visual or structural barrier to sharing. Multiple people can easily cluster around the device, and it can be passed back and forth quickly. This makes the tablet an inherently social object. Thus, like their analog counterparts, interactive books for children should encourage good social relationships between the child and their parents, teachers, or siblings. For example, interactive books can encourage relationships by including content that different age groups can enjoy, or different interactions aimed at different age groups. This way, older readers can be excited and can, in turn, excite younger readers. But younger readers still must have interactions they are capable of controlling.

Multiple modes. Story-driven books should consider different modes that suit different social contexts. For example, many story-driven books for children have a mode in which the device reads the book aloud so a child can enjoy the story alone, but this should be optional so a parent, teacher, or sibling can read the story instead.

Environmental

Computer desks are rare. Tablet computing happens on couches, in beds, in parks, and on busses. Interactions must be robustly usable from a number of angles. The user should be able to repeat interactions and the feedback for the interactions should be obvious as the user may not be fully attentive to the screen at all times. For longer books and reading materials, elegant methods of saving state are essential. Readers need to be able to pause and then resume reading as easily as they can with printed books, where they can stick their finger or a bookmark between pages to quickly mark their place.

Location may be important. Location is currently an untapped contextual factor for interactive books. Users could unlock chapters by going to specific locations. Content could make reference to external objects or places, blurring the boundaries between the on-screen content and the world.

Hardware

Hardware capacity. Current-generation tablet touchscreens are a step backwards in technical capability; a device like the iPad has limited graphics, sound, and processor capabilities. Hardware resource considerations are a focus point for tablet-based products. Designers should still seek to be ambitious and imaginative, but also be prepared to make some compromises about the type of effects or interactions they might want to include. In this context, for a product to succeed, good design must balance with technical constraints.

Devices may differ. There are differences between the device platforms that need to be taken into account. It is important to understand the sometimes subtle, sometimes obvious differences between products. Although an iPad and an iPhone 4 share much of the same hardware, there are obvious differences such as screen size that affect how an interactive book will display across the platforms. In contrast, an iPad and one of the upcoming Android tablets may share the same screen size and resolution but have very different hardware and operating systems. These differences will directly affect what can be achieved on each platform. It is helpful to identify the core design patterns that make up the interactive book so that a design can be scaled up or down depending which devices it’s being designed for.

Lesson #2 is that it’s too easy to get lost in the design detail and forget to understand all the ways a portable device will be used. Get a device to test your thoughts on (this advice can be used as an excuse buy an iPad). If you can’t get the device, then print a lot of wireframes and clip them to a block of wood that mimics the size and weight of the actual device. Take your real device or your pretend block of wood and give it to people, take it to the park, use it on the bus—understand how it fits into a user’s life patterns, and the many varied contexts it operates in.

Lesson #3: Testing Is Essential

Whether it’s a formal test or an informal one, the consensus within the UX community has always been that testing is key. In the emerging, largely unexplored area of interactive books, it’s particularly important because so many of the experiences that will occur are unexpected synergies between people, devices, contexts, and content.

It’s interesting to consider that tablet devices have made software more accessible to younger users. Any parent or caregiver can attest that young users are not just smaller versions of the bigger older ones; they think differently than adults. If you have forgotten what it is like to be small, energetic, curious about everything, and entertained in un-expected ways, then find a child to test your interactive book with. I make an effort to carry out constant ad-hoc testing with my own personal young app tester.

As an example of where testing uncovers unexpected interactions, on behalf of my company Demibooks, I tested a page from one of our upcoming interactive books, Astrojammies, by Stacey Williams-Ng.

Astrojammies by Stacey Williams-Ng, produced by Demibooks Inc.

The page displays a series of planets, which can be touched and moved. When a planet is touched, it plays a sound. Thus, there are only three core page effects, which combine to make rich interactions:

- Planets can be moved via touch.

- Planets continue to move and rebound based on collisions with each other or the screen frame.

- Every touch or collision results in a sound being played.

When adults engaged with the book, they never tried to play more then one sound at a time, so the page appeared work from an interaction and an aesthetic perspective. However, children have different exploratory habits and a much younger user quickly showed how children might respond by touching 3-4 locations on screen at once. The sounds had not been designed to be played simultaneously, so the resulting output sounded awful.

A murky chord

A quick revision to the sounds ensured that any sounds played simultaneously were always pleasing to the ear, regardless of how many were played at a time.

A wonderful chord

With applications that are used in varied contexts and by quite varied age groups, testing is a must. It does not guarantee success, but can help protect from un-expected and emergent behaviors.

Conclusions

Tablet-based interactive books are a unique chance to blend a number of disciplines, including art, storytelling, information and interaction design. Although this blending of disciplines is typical in any UX project, the combination of new touchscreen devices with the emerging interactive book medium provides never before seen opportunities. Although touchscreen tablets can function as a computer and include web browser, they are more than just a new type of PC. Tablets unchain users from desks or chairs and let them take their experiences out into the world. Although a touchscreen tablet can show the pages of a normal book, the sound, video, and interaction capacities of the device provide a new canvas to redefine what books mean to us all and how we interact with the stories they have to tell. The storytelling future that was once imagined in science fiction has become a reality.