Save

This article discusses some of the concepts covered in the author’s new book, Playful Design, published by Rosenfeld Media. You can get a 15% discount off the purchase of the book by using the coupon code “UXMag” at checkout, and you can also enter to win the UX Magazine giveaway for one of five free copies of the book.

This article discusses some of the concepts covered in the author’s new book, Playful Design, published by Rosenfeld Media. You can get a 15% discount off the purchase of the book by using the coupon code “UXMag” at checkout, and you can also enter to win the UX Magazine giveaway for one of five free copies of the book.

The popularity and ubiquity of electronic games have grown so substantially that gaming is emerging as one of most common ways people interact with machines. In past writings, I’ve argued that UX designers should incorporate game design into their toolbox of competencies. I’ve argued against superficially tacking points and badges onto “gamified” experiences that remain otherwise unchanged, and instead proposed that user experience designers can find much more benefit in approaching them as games first and foremost.

To do this successfully, however, we need to learn how to create high-quality player experiences. This is not a trivial task; the design choices that make for enjoyable games are very different from, and often contradictory to, the conventional imperatives of UX design.

Difficulty is a quality of player experiences that requires a truly radical shift in the way UX designers think. Normally, we would say that the less difficult it is for someone to do something, the better. There are rare and highly specific cases when an experience is deliberately designed to be somewhat challenging, as with systems requiring strong authentication or secure websites with short session timeouts, but this added overhead never improves the user’s qualitative experience.

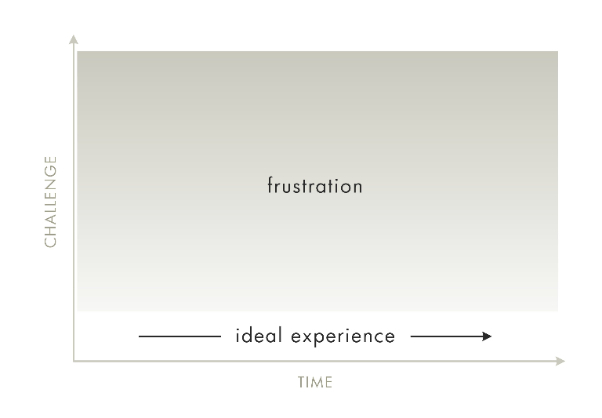

In ideal user experiences, difficulty is always minimized. Any challenge only increases the user’s feeling of frustration.

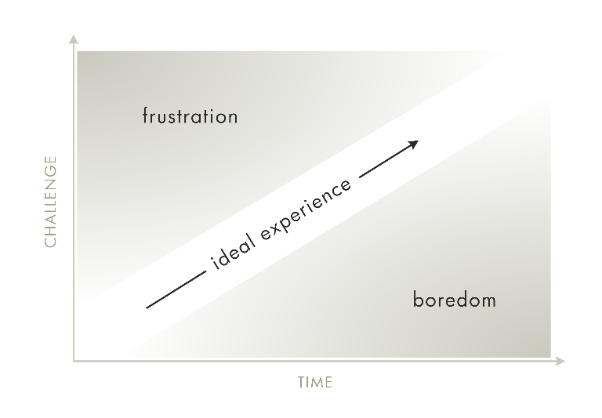

It’s an entirely different story for games. While excessive difficulty leads to feelings of frustration, too little challenge leaves players feeling bored. As a result, the ideal player experience falls into a narrow path between these outcomes. Successfully designed games keep players engaged in the experience by providing a feeling of continuous challenge and promoting the satisfying sense of growing mastery over time. Simply removing all sources of frustration would inevitably make the game less engaging.

Ideal player experiences balance difficulty in such a way that players feel don’t feel either frustrated or bored.

The tension between frustration and boredom in games is one of the perplexing dilemmas of game design that UX practitioners have no established models to handle. While our existing skills lend themselves very well to playtesting (evaluation of people’s qualitative experience of a game), we need a different way to think about problems like these. If you observe players having a tough time at some point in a game, how can you determine whether they’re actually having a “good-tough” time that will ultimately contribute to a sense of satisfaction with the game?

Distinguishing Real Problems from Appropriate Challenges

When a player has difficulty in a testing session, a few key questions will help determine whether it’s a worthwhile challenge or a true problem. Are players having a hard time for the right reasons?

First consider whether the source of the difficulty is the intended challenge of the design. As an example, let’s look at a simple case of a puzzle game that requires players to slide tiles around a board to put them in a certain order. If players are having difficulty getting the tiles to slide in the direction they intend, then they’re spending time on the puzzle’s interface rather than the cognitive challenge of the puzzle itself—an unambiguous usability problem. UX designers will find that their background makes them adept at identifying such issues and synthesizing appropriate fixes.

Now let’s consider a more complex case. Suppose that players aren’t tripped up by the puzzle’s interface, but instead have difficulty understanding what the puzzle requires them to do, or formulating the right strategy to complete it. These are arguably parts of the challenge of the puzzle itself and are not necessarily problems demanding resolution. Again, think about whether these challenges are intended parts of the design and whether the puzzle is more enjoyable because of them. If not, then clearer affordance or contextual help might be needed to prompt people to focus on the real challenge. But if they are an intended part of the design, you’ll need to consider the additional questions below.

Do players see the challenge as engaging or discouraging?

Observe whether the problem is damaging to the player’s willingness to keep at it. This question is tricky to evaluate because a person’s feelings of frustration may be only temporary. It’s even common for players who feel stuck to get up and walk away for a while, only to come back and decide to give it another go. It’s a good idea to allow players the latitude to do this in testing rather than making them feel strapped to the chair.

When players make comments like, “This is really tough,” you can ask them to clarify whether they mean it’s “good-tough” or “bad-tough”. Be careful to stay neutral, though, and not to ask too many questions that might change the way the players behave. You don’t want to lead them toward a conclusion they wouldn’t have drawn on their own. As well, keep in mind that players often won’t be able to give you a reliable answer. As with conventional experiences, there’s often a difference between people’s words and their behaviors.

As long as players show that they’re motivated to keep trying of their own accord, it’s a good sign that the challenge is engaging their interest and that the players would feel that it’s worthwhile. But if they truly give up, it’s time to assess whether the design should be changed. Even if they don’t quit outright, consider the cumulative effect of such experiences on players and whether they’ll be inclined to characterize the game as a whole as frustrating.

Is the level of challenge appropriate for the current stage of the game?

Ideally, games should start out by accommodating players who have very little skill. As the game progresses, players are prepared for the incrementally higher challenge of the next stage by merit of having successfully mastered the previous one, and the game gradually becomes more demanding of their skill.

In this light, consider where a given challenge falls on what should be a smoothly ascending slope. If previous experience didn’t provide sufficient practice for the current challenge, then players will be more likely to feel discouraged before they’ve given the game a real chance.

Super Mario Bros., for example, starts out by requiring players to master simple jumps and face off against enemies who don’t have especially potent offensive capabilities. But by the end of the game, players are timing jumps to moving platforms while avoiding spurts of erupting lava and fighting enemies that shoot fire and daggers. These feats can be difficult for any player, but they’re a reasonable challenge for players who have had time to practice with each of the elements earlier in the game. The same challenges would be too difficult if they came earlier in the game, prompting more players to drop out in frustration. In playtesting, measure the appropriateness of a challenge by the number of players who are able to successfully clear it, the number of attempts at it, and the total time to completion.

What in-game actions do players take in response to the challenge?

When trying to solve a problem, are people generally on the right track or do they attribute their difficulty to the wrong causes? For example, if a game requires players to find a key to open a door, do they start looking for the key or do they ignore the door and focus their attention on the useless window down the hall? People need to understand the nature of the problems they face and the actions that are available to them, and they must have a reasonable basis for figuring out what they need to do. They must be able to construct a model for understanding the problem in order to create theories about how to solve it.

By paying attention to how players react when they’re faced with a problem, you can get a sense of whether the design is what it should be. In the case of the door and the key, you might need to provide a stronger cue to direct players’ attention to the door and to suggest that a key is available—for example, telling the player, “This door can only be opened with a key,” instead of simply “This door is locked.”

How do players reflect on a challenge after surmounting it?

One of the best measures of a problem is how players feel about it once some time has passed since they overcame it. In retrospect, they may remember an experience that felt frustrating at the time as ultimately rewarding or as inconsequential in the broader context of the game. Don’t ask people to reflect on problems right away when negative emotions are still fresh. Instead, keep a list of the problems people encounter as they play the game, and when the testing is over, ask them to recall their most positive and negative experiences of the game. Then recount specific problems they faced, and ask them to comment on how they feel about them now. Persistent negative feelings about those problems are a good sign that the design should be revisited.

Mutual Benefit

It’s difficult to overstate the value of testing in the context of game design. In his influential book The Art of Game Design, Jesse Schell goes so far as to say that “good games are created through playtesting.” At the same time testing with real players is currently underpracticed in the game design industry, creating a gap where UX designers can contribute a valuable set of skills. You may find that providing testing consulting services can serve as a good introduction to the broader practice of game design. It’s a great opportunity to bring value to this sibling discipline while developing a critical eye for design.

However, games require significantly different approaches to testing than the ones ordinarily employed by UX professionals. The need to distinguish “good-tough” from “bad-tough” is one of many ways existing testing methods and practices require a shift to accommodate the unique needs of games. This kind of adaptation is really worthwhile for UX pros to undertake because it broadens our perspective on larger questions of design.

John Ferrara

John Ferrara has worked in in user experience design since 1999, designing interfaces for websites, desktop applications, and video games. Since 2006 he's been with Vanguard, and before that did significant work for Unisys and General Electric. He's been a forceful advocate for closer connections between UX and game design at the IA Summit, EuroIA, and Games for Health. He’s the author of the new book Playful Design: Creating Game Experiences in Everyday Interfaces, published by Rosenfeld Media. His nutrition education game Fitter Critters was a top prizewinner in the Apps For Healthy Kids contest, sponsored by Michelle Obama's Let's Move! campaign. Before entering the professional world, he earned bachelor's and master's degrees in communications. Feel free to follow John on Twitter at @PlayfulDesign.