In our first article about mobile technology and healthcare, we looked at the world from the patients’ perspective. This time, we’ll take a look at the world from the provider’s point of view. We’ll explore the ways mobile technologies are currently being used to enhance patient–provider communication, streamline coordination of care, and improve record-keeping. We’ll also discuss what stands in the way of wider adoption of these potentially life-saving technologies.

New Tools for the Old “Black Bag”

Mobile technologies are slowly gaining traction in the healthcare space, and our research indicates that for an increasing number of healthcare providers, smartphones and tablet computers are fast becoming standard equipment in every “medical kit.”

When Sean Parkin, a Physician’s Assistant working in Oakland, makes house calls, his iPhone is indispensable. It’s loaded with apps, including a multi-lingual translator that comes in handy when dealing with Oakland’s diverse population. It seems like such a simple idea, yet the right technology in the right place can make a world of difference.

Parkin is the first to agree. On one memorable occasion, he recalls, he couldn’t identify a patient’s rash. He snapped a photo with his iPhone, sent it to a colleague via MMS, and had a diagnosis in a matter of minutes. While using mobile devices to support clinical decision-making is a relatively new phenomenon, Parkin, and thousands of care providers like him, routinely use mobile-phone–based medical reference apps to ensure patient safety.

Parkin, in particular, uses his iPhone’s medication reference application to ensure proper dosing and to check for possible drug interactions. In his words: “I use my iPhone constantly throughout my work day—in the ER and offsite at patients’ homes. It helps increase patient satisfaction, too.”

Lab Coat? Stethoscope? iPad?

It may take a few years for iPads or other mobile computing devices to become as ubiquitous as tongue depressors at the doctor’s office. But we’re well on the way. Months after its release, the iPad is rapidly becoming de rigueur for medical students; Stanford and UC Irvine School of Medicine hand them out to incoming classes. UC Irvine’s iPads will come preloaded with hundreds of medical apps, course outlines and handouts, slide presentations, and required first-year textbooks in a digital format.

How useful is an iPad in a real-world medical environment? Dr. Henry Feldman of Beth Israel Deaconness Medical Center in Boston took one on his daily rounds for a week. The hospital’s secure wireless network gave Feldman access to all necessary clinical apps. This allowed him to use his iPad for admissions, follow-ups, coverage, and discharges, as well as to educate patients on upcoming surgical procedures, order on-the-fly diet changes, read and reply to email, and write patient reports.

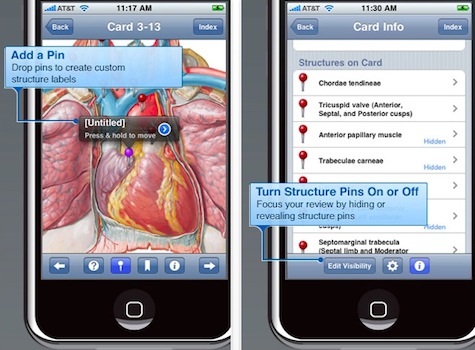

But what transformed the iPad from neat gadget to an indispensable tool was its ability to help Feldman demystify complicated medical concepts for his patients. After walking his patients through an upcoming procedure or diagnostic test using a popular anatomy flashcard application, many of them commented that it was the first time they’d fully understood their disease.

Thinking Outside the Desk

If you think our enthusiasm for iPads and iPhones was bought with a fat check from Steve Jobs, it wasn’t. Apple has captured hearts and headlines, but the lesson is universal: why bring the care provider to the data, when the data can come to the caregiver? Our examples illustrate places where care delivery, technology, location, convenience, and computing power converge for patients’ and care providers’ benefit.

Unfortunately, that’s not always the case. Take electronic medical records (EMRs), for example. In the race to ensure that every healthcare facility has an EMR up and running by the end of the year, usability has often taken a back seat and little attention is being paid to how EMRs are used, or could be used, in the “trenches” of care delivery.

EMRs are frequently envisioned, developed, and deposited in doctors’ workplaces with little consideration for (and even less observation of) how care delivery differs from facility to facility, or region to region. EMR systems are frequently computer-based, requiring laptops or desktops that tie doctors, nurses, and administrators to a single location for data entry while working jobs that keep them in motion for most of their workday.

This is especially concerning given the fact that many of the usability issues present in current EMR technology could easily be overcome if the technology moved to mobile device or tablet. Currently, care providers access patient EMRs on computers located in each exam room. If there’s no computer present, the care provider has to rely on notes or their memory to hold on to key information until they can return to a centralized or office-based computer for data entry.

When making rounds through a hospital ward, medical personnel roll heavy laptop carts and computers-on-wheels to capture patients’ vital signs. When computers aren’t present, caregivers note these all-important numbers onto charts full of scrawled notes, or onto any handy scrap of paper. One of our researchers once observed a harried nurse jot a vital sign in permanent marker on a patient’s hospital gown in response to a missing bedside chart.

Keep It Simple

The introduction of mobile access to and support for EMRs could solve many of these problems. Care providers would be logged on as they travel from room to room and their login process could be streamlined through the use of mobile devices. Tablet computers and mobile-phone–sized smart devices could support data capture on hospital wards as well.

The interaction simplicity fostered by smaller screen sizes might help application and software designers to examine the usability of their creations and, by extension, how care is actually delivered. The possibilities afforded by gestural interactions could simplify and quicken EMR interactions, thereby positively effecting the adoption and utilization of the system and reducing the chance for error.

Voices From the Front Lines

Designing mobile technologies for the healthcare provider space has some unique challenges. Often, providers are forced or otherwise pressured into using a specific system or type of system by hospital or network administrators. Not surprisingly, this prescription for technology is often met with resistance.

Adoption and utilization can also be issues if the technology does the opposite of what it was intended to do. For example, physicians often lament that writing prescriptions used to be as easy as scrawling some text on a piece of paper. The task now frequently requires prescribing physicians to navigate through many complex software screens to accomplish the same task.

The nurses on the unit are thrilled with the smartphone solutions. They save time—no more walking around the unit searching for a particular nurse. They reduce noise—fewer overhead pages if you can just text a colleague. And they make it easier for nurses to share critical patient care information.

Give the People What They Want

At Mad*Pow, we see that the next logical step is to tap into the social media capabilities of mobile computing devices. EMRs are currently little more than dumb data recorders, but imagine how much more they could be. The mobile platform could enhance physician–patient interaction by taking advantage of the very things that make mobile devices popular and powerful: the intuitive way they bake in communication methods and other forms of social media, their close proximity to their owners, and the fact that they’re perceived to be vital life-aids.

In addition to fostering communication, mobile device applications excel at providing straightforward mechanisms for patients to record vital signs, blood glucose levels, moods, steps walked, and any number of other transitory data that might otherwise never be recorded. Imagine if self-captured data could seamlessly integrate with EMRs and physicians’ decision-making tools? The conversation between physicians and their patients is suddenly infinite and data-based.

Our job, as UX professionals, is to design and develop mobile technologies that get that conversation started and keep it going, one voice at a time.