“The most powerful person in the world is the storyteller. The storyteller sets the vision, values, and agenda of an entire generation that is to come” — Steve Jobs

When I meet people at social gatherings and I’m asked what I do for a living, my response is: “I’m a storyteller.” It makes for a way better conversation than leading with “product management in a B2B SaaS company.” Truly, product managers and user experience designers are storytellers. We constantly need to be telling stories when communicating with everyone. We tell:

- Stories to engineers to build an amazing product.

- Stories to marketing to broadcast a captivating message to prospects.

- Stories to customers to inspire them to achieve great things.

- Stories to the executives and board to justify the ROI of our product investment, and the list goes on…

Being a good storyteller is why some product managers, marketers, and designers make the leap from Good to Great… and others don’t.

Let’s Become Great Story Tellers

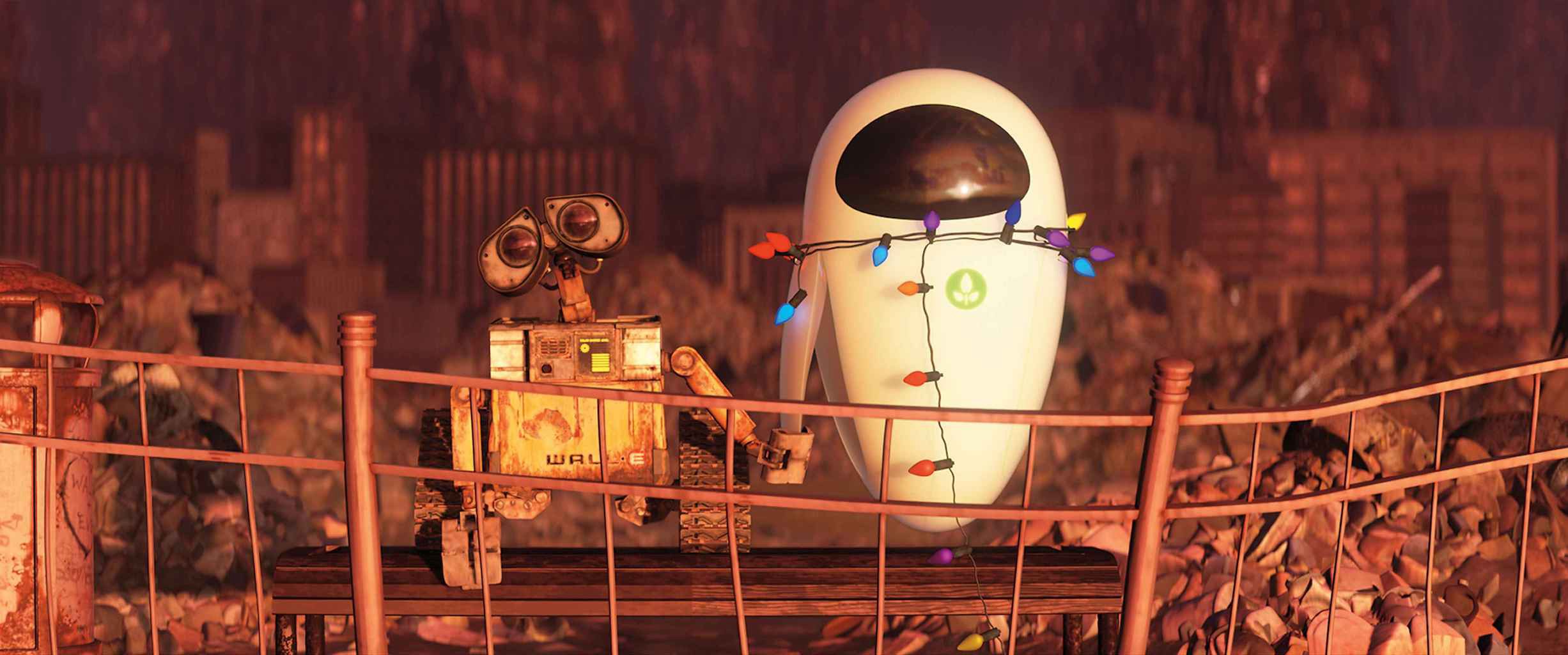

Emma Coats tweeted a series of basic storytelling tips while she was at Pixar. They became known as “Pixar’s 22 Rules of Storytelling.” She shared the valuable lessons from arguably the greatest storytellers of our generation, Pixar. Emma’s learnings from her days at Pixar inspired me to reflect on mine as a product person, and a storyteller. In the past couple of decades of building software, I’ve told many poorly structured stories and have learned to tell good ones. I’ve seen how a good story by a product manager results in a happy customer, and no story becomes a feature no one uses.

Here I’ve digested the relevant rules Emma presented, and reinterpreted them as:

Seven habits of great storytelling for product managers & UX designers — Inspired by Pixar

1. Without a purpose there is no story

We apply techniques like user stories, scenario narrations, storyboards, and journey maps. We paint a good picture of what happens as the user interacts with a particular product functionality. However, we often prescribe what should be built or how to use it — and neglect the underlying purpose.

What is the underlying message in the story? Like Clayton Christensen says, “People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill, they want a quarter-inch hole.” Ask yourself, am I prescribing the characteristics of the drill? Or explaining how the user drills the hole? Instead of articulating why the user needed a hole in the wall?

Before we start writing, we need to know why we are telling the story and what the purpose of the story is. In Emma’s words:

Rule #14 — Why must you tell THIS story? What’s the belief burning within you that your story feeds off of? That’s the heart of it.

2. Make me care

In a good story, empathy and admiration are born from the drama of seeing someone struggle in the face of difficult odds. Without sharing the drama the main character (our end users) is facing, the audience (engineers) don’t empathize with them enough to go the extra mile and solve their problem. Emma reminds us of how much we love a good underdog story:

Rule #1 — You admire a character for trying, more than for their successes.

Partly Cloudy | Pixar | Disney

3. A hero to root for

Everyone wants a hero to root for. Give me a reason why I should care for the hero of our story to get her job done. Why should I root for her success? What happens if she can’t get her job done using our product?

You may have great templates to document user and buyer personas, even have their first names and what the colour of their eyes are! Unfortunately that’s just a lame character in a boring story. If customer success is the end goal, what makes you care for this character as you read their persona?

What will the hero of the story lose if she is not able to overcome the obstacles to get her job done? Will they lose their job? Will the project fail and they will lose millions? Emma goes further and suggests we stack the odds against her as we author her story:

Rule #16 — What are the stakes? Give us reason to root for the character. What happens if they don’t succeed? Stack the odds against.

4. A credible storyline

Each scene in the story needs to be credible. We’ve all heard stories that have an overwhelming amount of unbelievable nonsense, and we’ve stopped caring for the hero.

We lose our audiences when our stories lack credibility — what the user’s objective is, what’s at stake, and how they can overcome obstacles. Instead of getting engineers to build out the acceptance criteria laid out for them, get them to root for the hero instead.

Rule #15 — If you were your character, in this situation, how would you feel? Honesty lends credibility to unbelievable situations.

WALL-E | Pixar | Disney

5. Impactful story structure

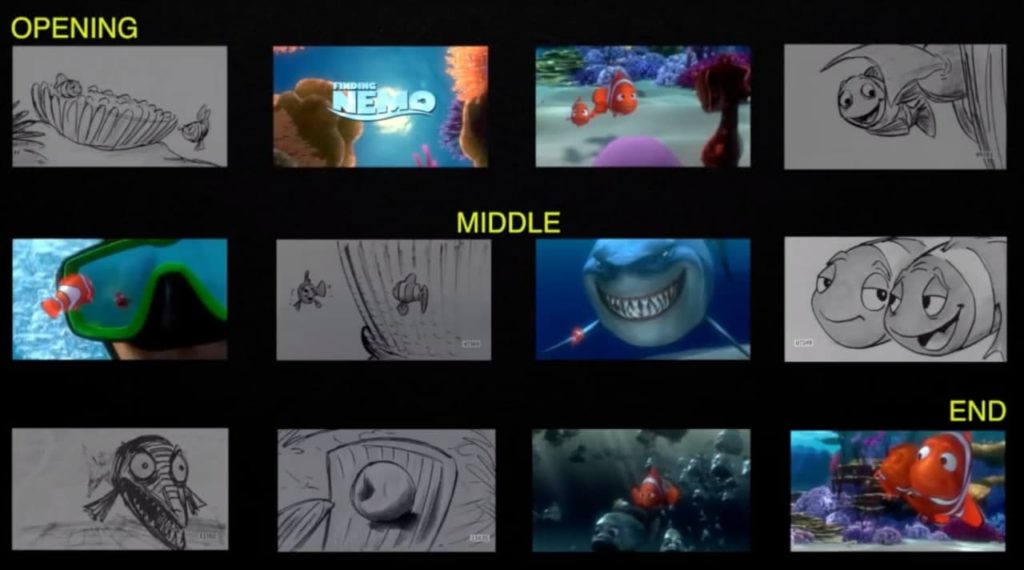

Every story has a start, middle, and an ending. A good story delivers the middle in a well-defined structure. Similar to a good speech, telling the story of a product capability is more impactful with a Tell-Show-Tell structure: First you Tell them what’s about to unfold, tell them you understand your user and what the user needs and wants to get done. Then you Show them how it happens. And finally to wrap up, you Tell them why they should care. What’s at stake if the job doesn’t get done.

Tell-Show-Tell method is commonly used for pre-sales demonstrations. It’s also applicable in product management and UX design. To elevate this method to Pixar level, we can apply Emma’s suggestion, which is Kenn Adam’s Story Spine structure:

Rule #4 — Once upon a time there was ___. Every day, ___. One day ___. Because of that, ___. Because of that, ___. Until finally ___.

Khan Academy video on this topic.

This structure is brilliant! For someone to buy and adopt your product, the pain of status quo needs to be greater than the pain of change. In the structure above, “every day” is status quo, “one day” is the event that tips the balance, series of “because of that” statements are the benefits they gain by switching to your product, and “until finally” is the expansion play. This format is just great!

6. What’s innovative about your story?

Who wants to hear the same story told, yet again, by yet another software vendor? What’s different about yours? You may be solving for the same “happily ever after” ending, but how does your story unfold differently? Emma’s advice is to not be afraid of throwing the first however-many iterations out, and starting from scratch till you nail it:

Rule #12 — Discount the first thing that comes to mind. And the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th — get the obvious out of the way. Surprise yourself.

Coco | Pixar | Disney

7. Begin with the end in mind

Rule #7 — Come up with your ending before you figure out your middle. Seriously. Endings are hard, get yours working up front.

Emma nails it in Rule #7: “Seriously. Endings are hard, get yours working up front.” It’s hard to know how to measure success after everything is set and done. Feature is built, shipped, and released… now what? What was YOUR Objective? What are the expected Key Results? Begin with the end in mind.

This approach creates a sounding board for us to reassess the validity of our decisions as change appears and we are forced to iterate our story and adjust the scope.

Breakaway from the habit of writing user stories and a bulleted list of acceptance criteria. Stop demoing features and listing benefit statements. Tell a good story, and you’ll end up with a passionate team that works on a product your customers Love.

Pixar | Disney

Thanks to Matt Crest, Peter Smith, Keith Cerny, and Mai Nakane.