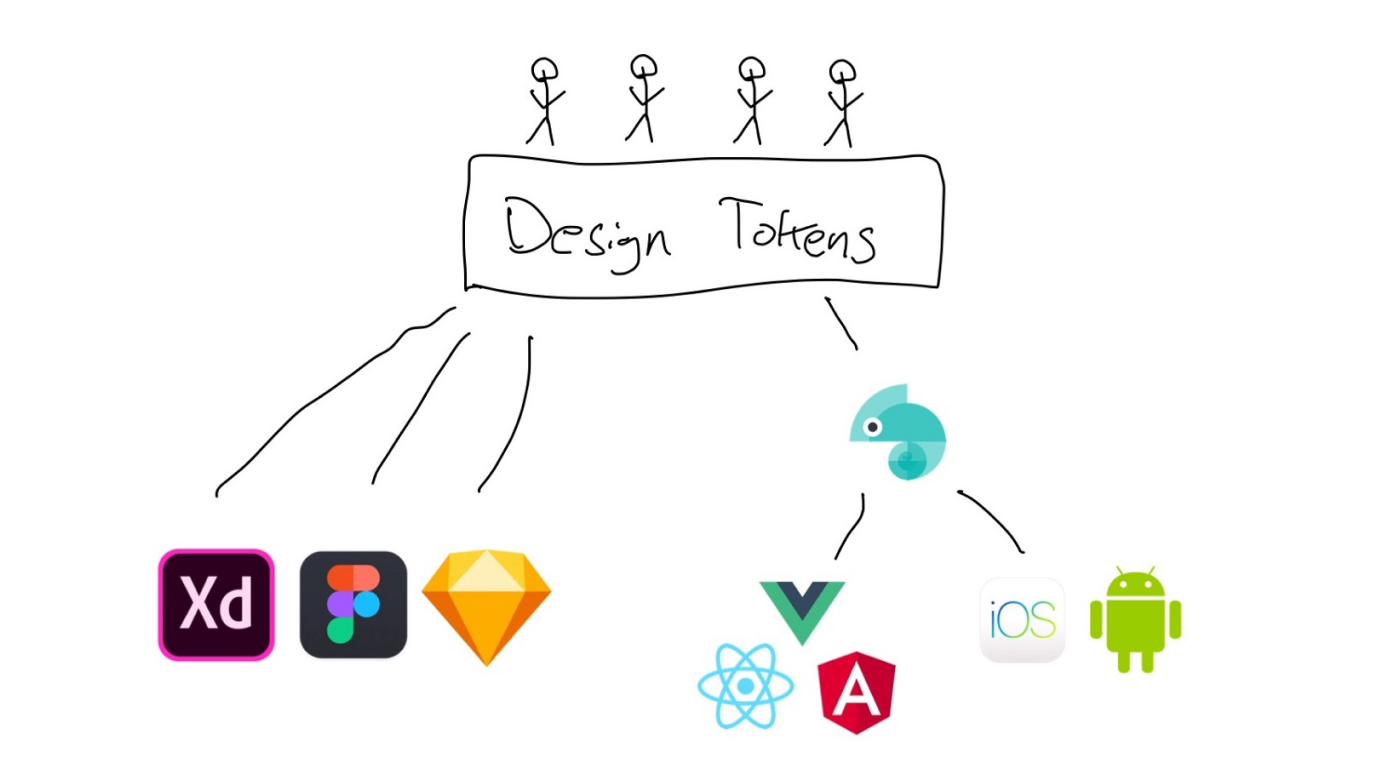

Everybody’s talking about design tokens — how to name them, how to organize them, how to use them, but design tokens aren’t just something that you can easily retrofit into your existing wardrobe. They require an entirely new way of thinking and working. If you want to start using design tokens, you need to start thinking in design tokens, and to start thinking in design tokens, you need to completely change how you think about design systems.

How we got here

Let’s step back and talk about design systems. What is a design system? Webster’s dictionary defines a design system as “I have work I need to get done and I don’t want to have to think about what color I should make this button.” Design systems are just a bunch of decisions (keyword, this will be on the test) that have already been made for you. Yeah, and they enforce consistency, promote brand awareness, empower users, save you millions of dollars, yadda yadda. So how do you make one?

The old way

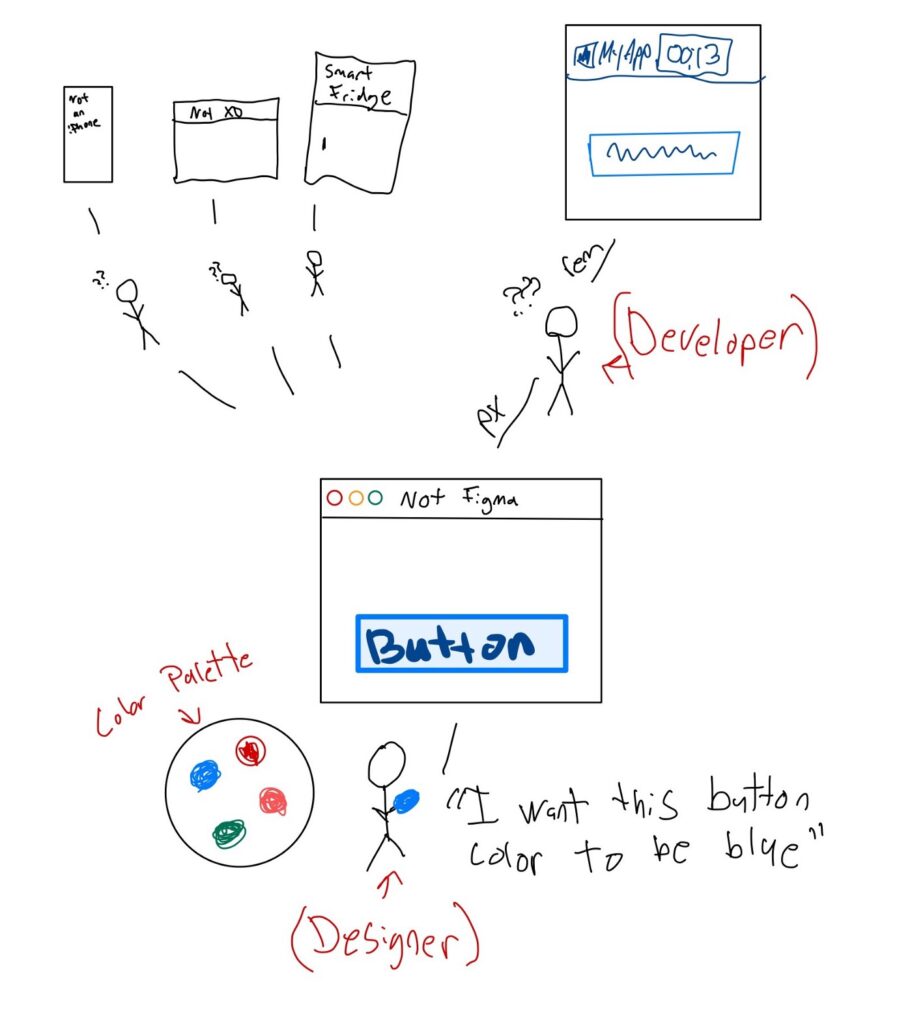

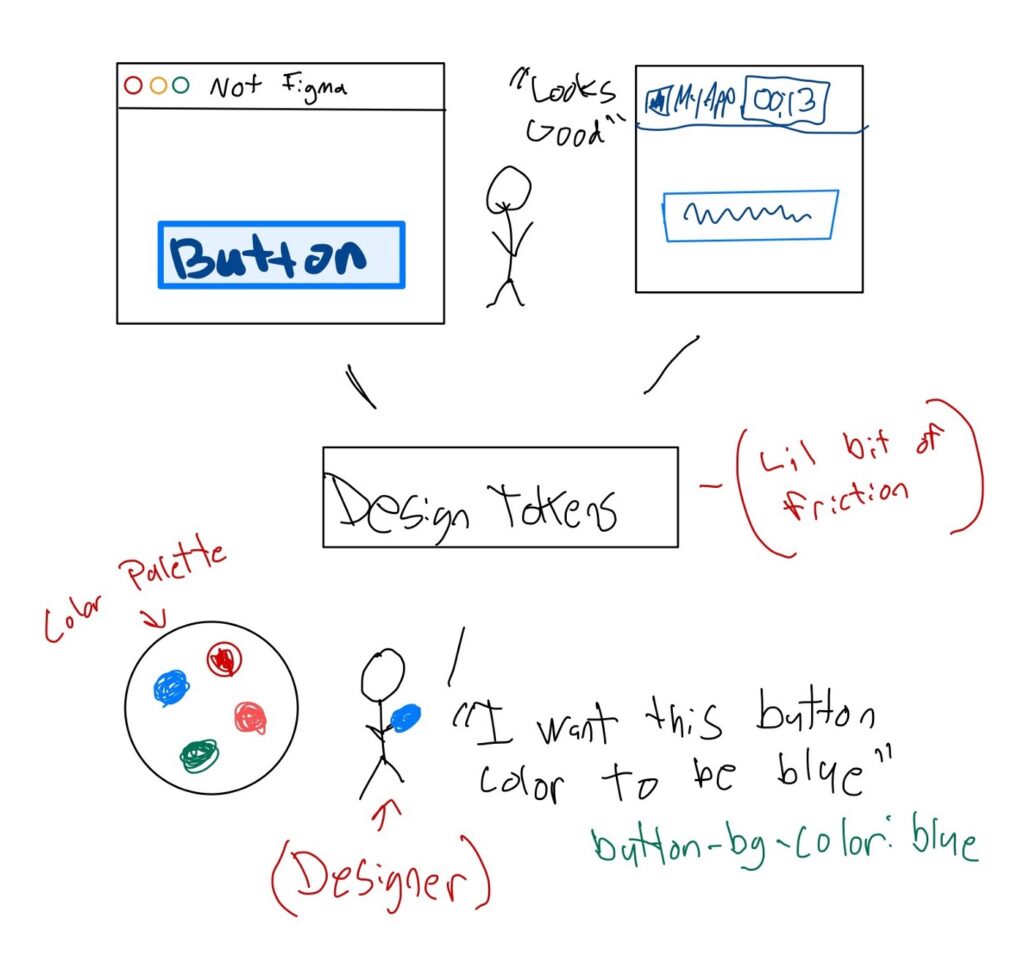

A typical workflow might look something like this:

Somebody wakes up one morning and says “we need a common design for buttons”. This feature then starts with a design team. The design team mocks something up in their design tool. They iterate. They turn in their deliverable. Somebody signs off on it. Now the design file is handed off to a development team, who will translate it into some code that somebody will use in an application. Sound familiar?

This baton-passing is how we’ve been doing it for years. It’s great. It makes sense, except design systems are never finished. They are living, breathing things. So in six months when we change our button color, now the development team needs to update their button code. And what happens if we change our primary color, which is what the button was using? Maybe we add a new state or a new variant. More batons, more chances for them to be dropped.

Adobe refers to their design tokens as “DNA”. I think that is a perfect name and a perfect analogy. Every time DNA replicates, there is a chance for a mutation to occur, an error in the copying process. Every time you change a design decision, you have the same risk for mutation when that decision gets copied downstream to other consumers. We want to reduce the number of times our design decisions are replicated.

Reframe your source of truth

In this example, our source of truth is the design file. Until design tokens came around, we haven’t had a great way of representing a design system as a tangible “thing”. Design files were the best implementation, but a design file is not the design system. It’s just one of many implementations. Design files serve designers. Design systems serve everybody.

In our example, in order to access the design system, a user must now:

1. Have access to the design file’s software

2. Have access to a device that is capable of running the design file’s software — operating system, minimum hardware requirements, etc.

3. Have some basic understanding of how to operate the design file’s software.

Next, they need to:

1. Decode the design decisions made in the design file.

2. Potentially translate some values to their specific platform, for example, a web developer may want units in rems while the design file defines them in pixels.

3. Encode the design decisions to their specific platform.

All of these things are barriers to entry for people who just want to know what color to make their button. Yes, you can and should be documenting your design system, but the documentation will always be a step behind your design file. What if there was a better way?

The way of the future, (the way of the future)

When a designer is working in a design file, they’re implicitly making dozens of design decisions. “The background color of this button is #f3f3f3. The padding is 20px. It should have a 3px border-radius”.

But what if they documented those design decisions at the time they made them? Instead of using the design tool to capture these design decisions implicitly, what if they captured them explicitly using something that was more accessible?

Imagine if they kept a notepad on their desk and every time they made a new design decision, they recorded it in their notepad in plain English. Now they can hand that notepad to all consumers of their design system and completely eliminate the decoding step because there is a shared language.

Now, recording design decisions in a notepad on your desk probably aren’t the best method though. You might use a third-party service, a google doc, a separate Figma page, or some JSON on GitHub. We use the Figma Tokens plugin and found it to be the least friction for designers because it allows them to work within the tool they are most comfortable with. The most critical piece is that your design tokens become the primary method for how you talk about and interact with your design system, both internally and externally.

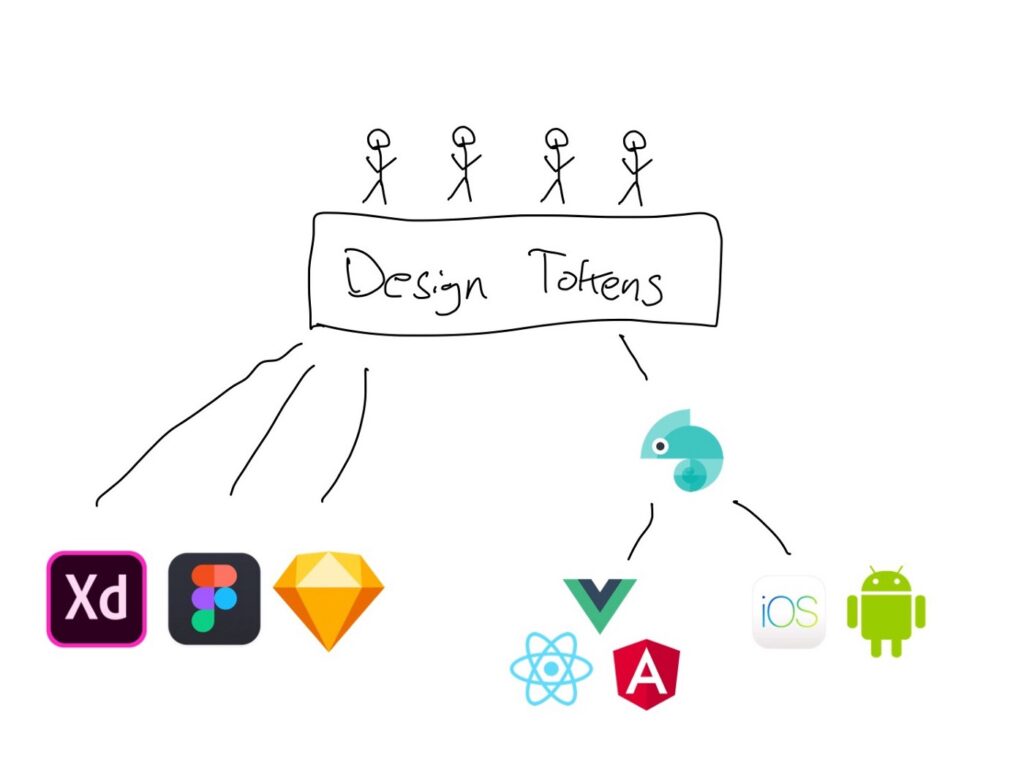

It’s all about a shared language

A funny thing happens when you start thinking about design tokens. When you shift your source of truth to something that is more universal, now you’ve opened up the lines of communication. Developers can have a more active role in the design system. Outside contributors can propose new changes. Everybody shares a common language.

[_Doug ordering from the Honker Burger for the first time_]

Doug: Hi, I’d like three double cheeseburgers, one all the way, one no pickles, one no onions, a fish sandwich, four large fries, and four grape sodas.

Honker Burger Lady: What on Earth are you trying to say?

Doug: What do you mean?

Honker Burger Lady: I can’t understand you.

Doug: Listen, my family is starving….

Skeeter: Yo, man, let me take care of this. The new kid wants three moo cows, one no cukes, one no stinkers, one wet one, four cubers, and four from the vine. Want anything else?

Doug: Well, how do you order a salad from the salad bar?

Skeeter: One salad from the salad bar.”

— Mosquito ‘Skeeter’ Valentine, Doug, S01E01

Design Tokens are our Mosquito Valentine. They allow users of multiple platforms and backgrounds (Doug, who doesn’t know anything about Figma) to communicate with our design system (the Honker Burger).

And sometimes, you really can’t come up with a better name than one-salad-from-the-salad-bar.

The Cost of Design Tokens

Design tokens have a real cost though. You’re offloading the encoding/decoding work that is required from end users of your design system onto the designers themselves. There is no getting around that, but the work is significantly less and the rewards are immense. In the end, you get a design system that is 1. Future proof 2. Accessible 3. Able to be easily changed.

Design tools change. We had Photoshop, then Sketch, then Figma. Platforms change. We had desktop computers, mobile devices, iOS and Android, watches, tablets, TVs, and refrigerators. Everything changes, but a button will always be a button.