Looking back at early design systems can reveal timeless insights to inform today’s digital transformations.

The dawn of design systems

In our modern digital era, the term design system is primarily associated with user interface (UI) development. It describes a structured set of components, guidelines, tools, etc. used to deliver consistent digital experiences. But if we broaden the definition and apply it to history, “design systems,” or systematic design — whether in architecture, publishing, or manufacturing — have been integral in driving human innovation since the dawn of time.

By looking at design systems through that broader historical perspective, we can literally draw upon centuries of data to better understand design’s influence on society — and draw parallels to today’s digital world.

One could argue that design systems date back to the Stone Age. From weaving baskets to crafting jewelry and textiles, prehistoric people mastered systematic thinking thousands of years ago, as evidenced by archaeological finds.

Imagine what it was like, to produce textiles using ancient tools, by repeating patterns, using symmetry, balance, and proportion — principles that closely resemble early mathematics. Even without formal geometry, our ancestors applied structured thinking to their crafts, many years before civilization.

In many ways, these early designs were practical forms of problem-solving, blending art and logic to high levels of sophistication. Their processes, much like modern design systems, aimed to create consistency, order, and beauty, something we still strive to achieve today.

I’ve come to realize that art often precedes science — because it involves solving problems in ways that aren’t immediately clear — or even fully understood — until the solution is found. It’s been said, “Art is solving problems that cannot be formulated before they have been solved. The shaping of the question is part of the answer.” (Piet Hein)

The creative process itself is a form of problem-solving, where artists apply structure, proportion, and technique using instincts at first. Over time, this creative exploration often uncovers patterns, systems, and methods that later become formalized into scientific principles.

Takeway #1: Art explores possibilities, and in doing so, it often discovers the very questions science later seeks to answer.

Even today, this is why the most successful creative teams have a clear separation (and balanced relationship) between discovery and engineering. Both need to be independent of each other, while each depends on the other for success.

So let’s move on, and see what else history can tell us about where we’re heading.

Movable type and the printing revolution

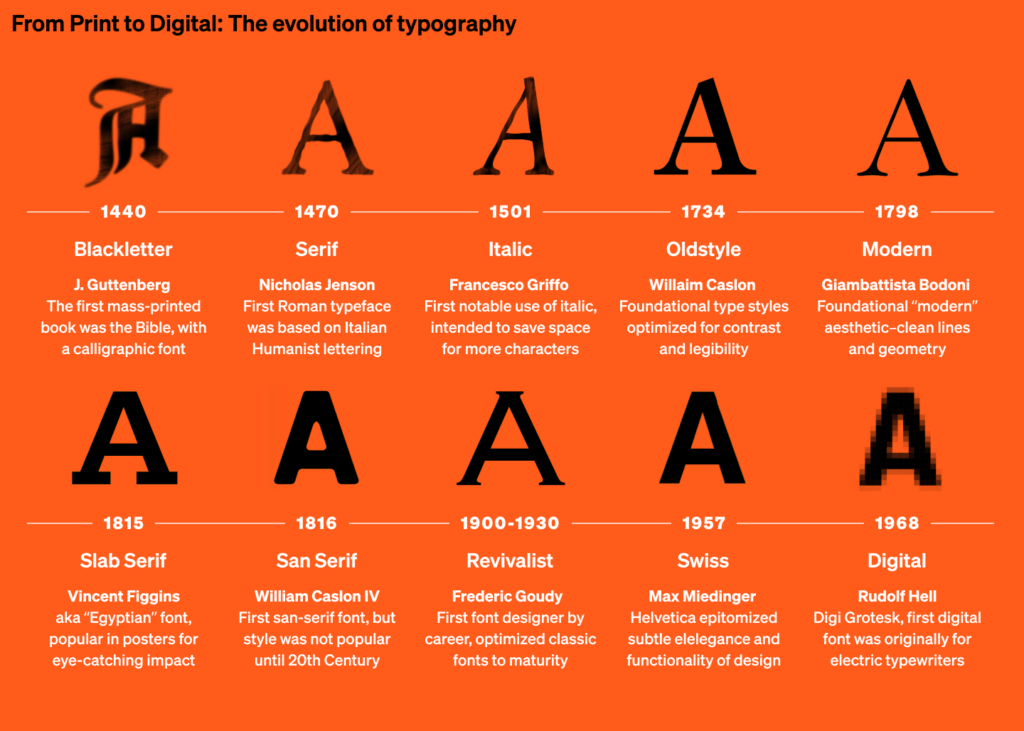

One of the earliest and most significant inventions of the modern era was printing. When I was in elementary school, history lessons often began with the invention of movable type in 1440, attributed to Johannes Gutenberg. But this narrative, while popular, is not entirely accurate. The movable type was already developing in Korea, albeit in a more limited, less systematic way.

It wasn’t until Gutenberg — a goldsmith by trade — perfected the metal alloys needed for mass production of precisely cast letters for movable type to become viable at scale.

We can see similar patterns of scaleability throughout history. A classic example often cited is Henry Ford. While he didn’t invent the automobile, he created the methodology of the assembly line. Ford’s innovation wasn’t just about the product, but about the efficient and scalable system that made the automobile viable as a product.

Takeaway #2: An invention is not a product until the method of production is made viable.

By looking closely at the history of technological innovations, we keep drawing more parallels to today’s breakthroughs. In this new era of both wonder and uncertainty, where transformative change seems imminent, the expression “past is prologue” continues to fascinate me.

Just as Gutenberg’s press democratized information by making books more accessible, the rise of the internet and digital platforms has revolutionized how we access and share knowledge.

In both cases, the initial breakthroughs — movable type in the printing world and the creation of the internet for digital communication — were just the beginning. What followed were incremental improvements that took time to mature until the next breakthroughs and game-changing paradigms arose.

Printing technology’s slow, steady evolution

While Gutenberg’s press revolutionized printing, many aspects of the process remained fairly unchanged for centuries. Typesetting and the manual operation of presses were still the norm.

The impact of the invention was undeniably profound — before printing, only a few thousand books were in existence in the whole world — the printing press brought that number into the millions. Yet, for centuries, only a tiny fraction of the people would have access to books. Why?

The path to modern printing and the standardization of written language were not without challenges. It’s a long story, but it offers valuable insight into how systems evolve over time. It also shows how technological progress, even with the best intentions, can lead to major obstacles and glitches.

The bumpy road to standard language

This story begins with William Caxton, the first to print books in the English language, who had an enormous impact on standardization (and some incredible mistakes in the process). Before Caxton’s time in the 15th century, most printed texts were in Latin, the scholarly and religious language of the day.

Caxton took on the task of translating and printing works in English to make them more accessible. However, this task would prove to have extraordinary consequences for the future.

At this time, English was undergoing rapid transformation. The Great Vowel Shift, which changed the pronunciation of long vowels, was underway, complicating efforts to align written and spoken language.

English had lacked any standardized spelling, and regional dialects varied widely, so aligning which dialect or spelling conventions to use was difficult and arbitrary. On top of all that, the master typesetters Caxton recruited from Europe had limited knowledge of English, and looked to Dutch and German for answers.

This led to a “perfect storm,” in which printed English became riddled with inconsistencies and random changes. His works, though groundbreaking, contributed to the chaotic development of English spelling, which remains highly non-phonetic, irregular, and irrational to this day — making English one of the most difficult languages for non-natives to master.

Takeaway #3: The rapid adoption of a new system, without careful understanding of its broader implications, can have long-lasting negative effects.

The rush to print in English, while democratizing literacy, inadvertently contributed to centuries of confusion over the language’s system of logic (and impact on current communications). This serves as a cautionary tale for modern systems, particularly in technology, where rapid adoption without proper safeguards can create long-term and irreversible complications, as we will see in the rest of this story.

Challenges in early printing: slow adoption, incremental improvements

For decades, printed books were an expensive luxury, not easily accessible to the general public. Early printing faced several key challenges, including high costs, low literacy rates, and the intense manual labor required to produce movable type — imagine setting every letter on a page with pieces of metal, backwards, on a tray, swabbing that all with ink and pressing a piece of paper over it, then hanging each page up to dry, one at a time. Even worse, you couldn’t save so many trays of letters; you would often need to start over and recycle the letters you have for making new pages.

A printing press requires specialized knowledge and skilled labor to operate, making it primarily a craft. Typesetters were in short supply and expensive to hire. This pattern seems to repeat itself throughout history with each new technological leap. From telegraph operators in the mid-19th century to software engineers today, democratizing a system doesn’t mean it becomes accessible to everyone right away — it still requires specialized skills to operate within the system. Here in the digital age, only a tiny fraction of us can write code — by some estimates, less than 1% of the world’s population.

Takeaway #4: Emerging technologies often need special skills at first; over time, they evolve to become accessible to a broader audience.

Along with the high specialization of printing skills, low literacy rates and limited access to books created a feedback loop that slowed the spread of printed materials and literacy itself.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, books were scarce and expensive, and literacy was primarily limited to the elite, clergy, and scholars. Since there were few readers, there was little incentive to print large quantities of books, which in turn kept literacy rates low, especially among the general population.

However, over time, as printing technology improved and books became more affordable, literacy rates gradually increased. This fueled greater demand for printed materials, creating a virtuous cycle that eventually broke the initial paradox.

Another significant barrier was the availability of materials. Paper, while increasingly common by the 15th century, was still an expensive commodity. It would take centuries for paper (and oil-based ink) to be more easily affordable.

Takeaway #5: Scientific advancement, robust infrastructure, and societal readiness are the essential ingredients for transformative change.

Societal issues and advances of printing

A major challenge was censorship and regulation. The Church and state, realizing the power of printed books to disseminate information widely, sought to control what could be printed. This stifled the flow of information and limited the growth of the industry in its early years.

Another challenge was skepticism toward the new technology of printing. Initially, some viewed printing as a lesser substitute for the artistry of hand-copied manuscripts. Important documents, like the Declaration of Independence, were proudly handwritten to convey prestige and authenticity.

This pattern of resistance to new technology has quite often been repeated throughout history. For example, the introduction of the telegraph faced similar pushbacks, with many seeing it as unreliable compared to written letters.

The same was said about the first automobiles vs. horses. Further, in time, self-driving cars are not widespread today. Why? The technology is there, but we’re just not ready for the change?

In general, by the early 20th century, the rise of mechanical assembly lines was slammed by traditional craftsmen, across industries, fearing the loss of quality in mass-produced products (and the loss of their crafts).

Even today, we see this pattern with digital art and AI-generated content, which some argue doesn’t have the “soul” of human-made creations.

Takeaway #6: Skepticism of new technology gradually disappears as the technology evolves, proving its value and gaining acceptance.

Limitations of early printing practices

Early printed works were often religious texts, scholarly works, or legal documents, which had a narrow, educated, and often wealthy audience.

Printing presses were typically located in cities which had the infrastructure and money to support the business. However, at the time, most of the world’s population was rural, so access to books and printed materials was well out of reach, for a long time.

The broader market for entertainment, news, or practical information had yet to be developed to a degree that would drive mass production of books, pamphlets, or any other sort of reading material.

Slowly, the development of better inks, more durable types, and more efficient presses gradually improved the speed and quality of printed materials.

Takeaway #7: What is “good enough” stifles transformation. True disruption happens when market pressure forces outdated techniques to become obsolete.

The industrial vs. digital revolution

Among the most significant innovations in printing was the steam-powered printing press, which emerged in the early 19th century.

Industrialization ushered in a broad societal shift toward efficiency, and automation, and a new accessibility to products and services that were previously unheard of for most people. Printers could now produce thousands of copies daily, making printed materials common.

The upshot of this was the birth of mass communication. As newspapers and books became more affordable, public literacy skyrocketed, and ideas spread across all social classes, not just the elite.

Takeaway #8: Efficiency and automation don’t just add value to products — they are the key to making those products accessible.

Just like in the early days of mass printing, the evolution of digital media was fraught with issues concerning quality versus convenience, and whether speed and accessibility came at the cost of depth and professionalism. Old traditions give way to new standards, sometimes with significant downgrades at first. Those who remember the World Wide Web in the 1990s can attest to that.

Takeway #9: Technological advancements in communication present a tedious balance between innovation and tradition.

The dark side of mass communication

One of the less obvious but significant effects of the Industrial Revolution on printing was its influence on cultural language and stereotypes. As steam-powered presses increased production, they also made it easier to reproduce common phrases, imagery, and motifs — the building blocks of cultural clichés.

The more frequently certain ideas or expressions appeared in print, the more they became engrained in the public consciousness. The rapid reproduction of content gave rise to the concept of “stereotyping” in both a literal and figurative sense–printing presses used metal “stereotype” plates (a single cast of a block of text, also known as a “cliché“) for quick reprints, but this mechanized reproduction also fed into the overuse of familiar narratives, locking them into the public mindset.

This concept of “cliché” extends beyond just repetitive blocks of print; it not only became a vocabulary word, but a real danger to society.

Standardization sounds great, but cementing patterns of thought, creating stereotypes, promoting misinformation, and weaponizing propaganda are all byproducts of technology gone wrong.

If this sounds familiar, it should. This is not unlike today’s digital age, where repeated algorithms and automation threaten to make digital content increasingly formulaic, limiting creative expression, and creating feedback loops in the echo chambers we all live in today.

Takeaway #10: Without proper guardrails, the power of mass communication can amplify misunderstandings and reinforce harmful beliefs.

Let’s consider how the terminology from the printing world has crept into our digital age. Words like “font,” “typeface,” “leading,” and “kerning” have their origins in the physical process of typesetting and printing and continue to dominate modern design language, even when they barely make sense, for instance, using the words “page” or “canvas” to describe a digital experience.

These remnants of the printing era not only reflect the technical evolution of media but also hint at a deeper cultural impact. The persistence of this jargon shows how deeply rooted print culture was in shaping our understanding of communication and design, even as we transition to digital formats.

In this way, the legacy of printing has extended into our cultural framework, influencing how we approach new technologies. The rise of clichés in print paved the way for digital shorthand and memes, while the enduring jargon reminds us that every medium carries with it the weight of its history.

As we stand on the cusp of new revolutions in technology, the challenge is not just to innovate but to avoid falling into the traps of stereotyping — to ensure that we create something truly new rather than simply reproducing the past. Already with the rise of new technologies, clichés of the digital era are entering our new AI-driven future.

Takeaway #11: With every new leap in technology, vestiges of past concepts are slow to disappear from our common understanding of things.

Interestingly, the early forms of movable type were modeled after the calligraphic letterforms of medieval monks, a reflection of their cultural heritage. The bonds between craftsmanship and culture have always been strong, and it is likely that today’s standards will eventually become tomorrow’s legacies — vestiges trapped in our common memory.

Echoes of the past: how language and culture shape our technology future

What other phrases may become quaint, classic, or standard as we stand on the brink of the Gen AI era? Change is inevitable. We may not even refer to it as AI in a few years — just as we no longer talk about the “information superhighway,” a term that was quickly retired. Just as “Cyber Monday” makes little sense anymore — nearly everyone has a personal computer or smartphone now.

Emerging technologies don’t just grapple with legacy jargon; they compel the reshaping of entire processes and workflows, forcing industries to adapt or risk facing consequences, or worse, obsolescence.

Case in point, the system of HTML, starts with a simple text prompt, much like the earliest forms of digital communication. Think about this: we launched the information age with a DOS prompt — a blinking cursor waiting for input — and it’s still part of the tech stack we use today. Ostensibly, it’s not so different from Ben Franklin, laboring in his Philadelphia Print Shop with a wooden tray and pieces of lead text, it’s just that our tools have gotten a lot fancier.

A parallel universe, with a divergent internet

Imagine, in a parallel universe, that the timing was different. What if Apple and Adobe had teamed up to develop a graphical web browser in 1990? In this scenario, everyone would have been browsing the internet with a slick, low-bandwidth experience in PDF instead of clunky HTML. Perhaps HTML would have faded into obscurity, and EPS dominated all the web standards.

What impact might that have had on software engineering and web design today? Would the internet be fundamentally different if it had started with a creative design system already in place? While the questions are hyperbolic, it underscores a broader truth: technology, adoption, and design standards often intersect in ways that shape our world in curious and unexpected ways.

As technology advances at an ever-increasing pace, we must consider how cultural legacies might impact our progress. A great example is the QWERTY keyboard. Originally designed in the 19th century to prevent mechanical typewriter jams, this layout was intended to slow down typing speed.

Ironically, this cultural artifact has persisted, limiting typing efficiency for generations. This raises the question: how many other outdated cultural legacies might be inadvertently hindering technological progress in ways we’ve yet to recognize?

Takeaway #12: The adoption of a system has its own momentum and can ultimately determine the trajectory of a new technology.

Digital revolution, slow evolution of design systems

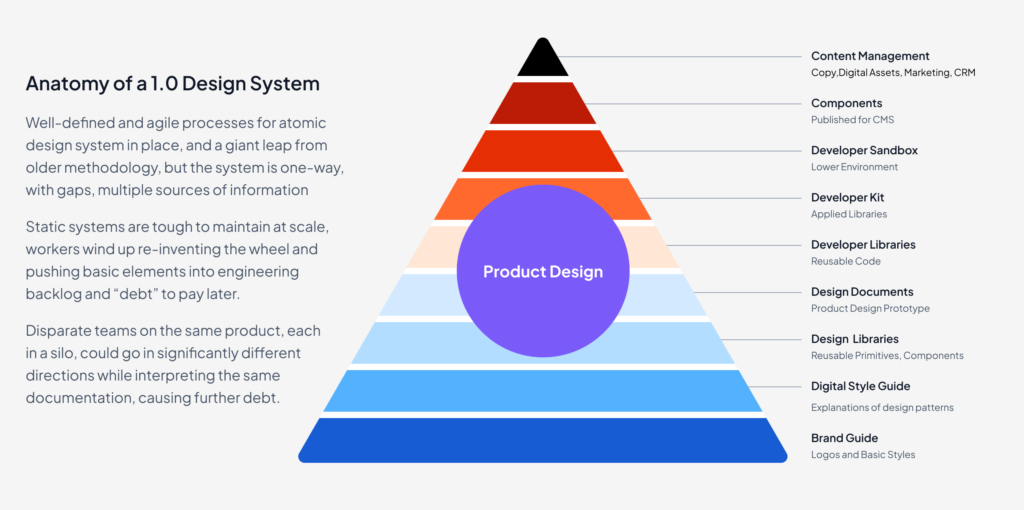

By the early 1990s, the rise of graphical browsers coincided with the growing power of personal computers and rapid advances in desktop publishing software. Programs like QuarkXPress, and later Adobe InDesign, enabled teams to maintain design systems by sharing reusable pattern libraries.

While the internet rose very quickly, the widespread adoption of systematic design didn’t take hold until decades later. Why?

As a designer, I’ve pondered this for a long time. Could the limited reach of early design tools have hindered more collaborative workflows? Consider that desktop publishing software, while powerful and transformative, was primarily used only by designers. These designers were often focused on guiding front-end development rather than creating comprehensive, reusable systems for digital publishing.

During the Web 1.0 era, manual processes were the norm. Designers and developers worked in isolation, using different tools to create web pages. Engineering handoff typically consisted of a few static prototypes, information architecture blueprints, functional specs, and copy decks, all of which had to be manually input and interpreted by developers.

Takeaway #13: Early digital design systems were challenged by fragmented collaboration between designers and engineers, limiting cohesive solutions.

UX design was still maturing, with pioneers like the Nielsen Norman Group providing guidance and training. Despite the evolving design practice, the tools designers used — primarily Adobe Photoshop — remained stagnant for nearly two decades.

In 2015, I worked on a project for a financial data portal. Our team quickly realized that the scope of the project was much too large for Photoshop, which struggled with managing hundreds of screens, dashboards, and data visualizations. Instead, we opted for Adobe InDesign, which allowed us to manage objects iteratively and effectively within an agile workflow.

In hindsight, this decision was a success, but it was controversial at the time due to adoption patterns. InDesign was primarily used by print designers for its object-oriented approach, which allowed large image files to be managed separately from other objects. It was ideal for large-scale print projects but perceived as less suitable for digital projects.

Why Adobe InDesign failed to dominate digital design systems

Several factors prevented InDesign from catching on with digital designers. First, the need for sophisticated design systems didn’t arise in typical Web 1.0 workflows. Second, InDesign’s complexity was considered overkill for fast-paced web design. Finally, its use of points (a printing measurement system) instead of pixels hindered its ability to produce pixel-perfect digital designs. By the time Adobe addressed this with InDesign Version 6 in 2012, it was too late for widespread adoption by digital designers.

How did the long winter of design systems end?

The slow evolution of design systems from the 1990s through the 2010s reflects the limitations of the tools available at the time and the separation between design and development processes.

As the demand for scalable, systematic design grew in digital media, new software, platforms, and subsequent workflows emerged to fill the gap, shaping how we think about design systems today.

Takeaway #14: Technology adoption isn’t just about the tool — it’s about the right solution meeting the evolving needs of industry — at the right time.

By the early 2010s, everything began to change. Social media platforms democratized publishing, unleashing a tidal wave of creative output across the web. Businesses that once viewed the internet as a digital brochure started exploring new possibilities as server technology lowered the cost of ownership. This was called the beginning of “Web 2.0.”

The slow burn of incremental change suddenly accelerated. With new tools and more widespread adoption, design systems became essential. UX practices evolved rapidly, and the convergence of design tools, technology, and adoption gave birth to the design systems we use today.

As we look toward the future, the history of design systems continues to offer insights. We’re on the cusp of another technological revolution in AI. What will this mean for design? Just as the printing press transformed communication, AI may reshape the way we create things and interact with each other.

The only certainty is change. As we move forward, we can look to the past for guidance, learning from the lessons of history to make informed decisions about where to invest our time, energy, and creativity in the years to come. But before we get to that, let’s examine some more recent history, the period between 2016 and 2024, where the practice of design systems has come to mature and is directly shaping the conversation we need to have today, in the next article in this series.

The article originally appeared on Medium.

Featured image courtesy: Jim Gulsen.