Save

For the past several years, I’ve been looking at ideas from psychology we can apply to interaction design—ideas such as curiosity, scarcity, or feedback loops. This exploration eventually led to my book, Seductive Interaction Design, where I looked at designing sites and applications using a dating analogy. Of course you can’t discuss a topic like seduction or what motivates people without some awareness that, no matter how playful or well-meaning your intentions are, these things will certainly be abused. So I’m often asked this question on the subject of ethics: “When is it okay (or not okay) to influence someone’s behavior?”

Here’s my simple response: Don’t take on projects that you wouldn’t personally use yourself or recommend to your friends and family.

When you agree to work on a project, you make an ethical choice. The question of ethics begins with the clients you choose to take on, not the tactical design choices you make along the way.

Drawing an Ethical Line in the Sand

In 2002, Milton Glaser wrote the incendiary essay The Road to Hell, which challenged graphic designers to think about where they drew the line on bending the truth. While the article was aimed at advertisers, Glaser’s depiction of a slow gradation from “Designing an ad for a slow, boring film to make it seem like a lighthearted comedy” all the way down to “Designing an ad for a product whose frequent use could result in the user’s death,” helped me to define my level of discomfort and where I drew the line. What kinds of projects did I want to support with my time and talent?

Around the same time I read that article, I was doing some work for a health insurance company. No ethical issues there, right? It’s not like providing insurance is at all in the same league as selling cigarettes. As it turns out, during the redesign of their website, huge amounts of time and money were dedicated to the sales portions of the site. We designed a more engaging homepage, improved how services were explained and promoted on the site, and made the enrollment forms much easier to use. But, when we got to the support side of the site—answering FAQs about itemized vs. non-itemized receipts, clearly explaining the process associated with filing a claim, and so on—the client was content to leave these pages untouched. By leaving these pages difficult to use, they were able to reduce the number of claims processed. They knew that customers frustrated by the process would often give up hope of ever seeing their money reimbursed.

I took issue with this conduct, and once my obligations on the project were over, I swore off working for health insurance companies, or at least ones that operate this way. Depending on your ethical stance, this example may also infuriate you, or you may think I overreacted. My point is simply this: we should all determine ahead of time where we draw the line.

Conflicting Ethics

Unfortunately, our society doesn’t adhere to a universally agreed-upon set of ethics. We do have social and cultural norms, but within those norms ethics can vary greatly. In his book Persuasive Technolog, BJ Fogg offers a practical methodology for analyzing ethics. He recommends that you list all the stakeholders—anyone involved with the persuasive technology. Next, list what each stakeholder has to gain and lose. Then evaluate which stakeholder has the most to gain and who has the most to lose. And finally, determine ethics by evaluating the inequities between different stakeholders. He also cautions that we acknowledge the values and assumptions you bring to your analysis.

Even with helpful tools like this, making the right choice is rarely black and white. There are often competing ethics: your professional obligations, feeding your family, sticking to your personal moral convictions, etc. Things get even more complicated any time you zoom out and look at macro-level issues such as sustainability or the long-term effects of products on societies. Are tweeting and check-in services harmless? What if these activities isolate individuals from social interactions— is this good? Be conscious and aware of what you’re endorsing with your time, not only for the welfare of others but for your own sense of self. The work you choose to take on defines you.

Ethics and Persuasive Tactics

Let’s return to the question of ethics and persuasion.

There’s a hidden benefit to only taking on projects you believe in: it helps you avoid the more difficult question of, “How far do I go in influencing behavior?” Are seduction techniques like the ones I describe in my book ethical? This is a difficult question to answer.

If you hire a lawyer to defend you, you expect that person to do everything in his power to prove your innocence or ensure you get a fair trial. If you hire a personal trainer to help you shed some pounds, you expect that person to use the tools and methods at her disposal to help you reach your goals. Similarly, if someone hires you to create a new homepage that leads to more sales, they expect you to use whatever skills you have to accomplish this goal. Do you hold back? I believe the moment we commit to design something, we’re either all in, or not. Which means we should choose projects with care.

But can we go too far?

What if a site uses scarcity (“Only 3 left!”) to encourage people to buy something?

Is this unethical? Or have you ever simply made a button bigger so that more people would click on it?

Is there an ethical difference between these two examples? In both cases a decision is made that will influence behavior. Scarcity will probably be more effective; is it wrong to use a tactic because it’s more effective? If you don’t recommend the best, or even a better, way to accomplish a goal, does this make you a bad designer?

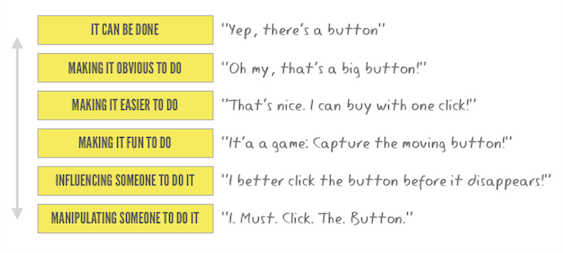

I think many of us have a kind of mental scale in our minds, something like this:

We look at this scale, ranging from harmless to “evil,” and draw our ethical line somewhere along it. “Everything on this side of the line is ok. Everything on the other side is wrong.” A line like this a great for ethical issues (like those described by Glaser), but I’m not so sure this kind of scale applies to the methods of persuasion.

I’m arriving at this conclusion after having observed a number of different arguments for and against persuasive tactics. If we’re going to draw a line somewhere on the scale above, we need to have coherent reasons for this view.

Our Judgements of Persuasive Tactics Are Inconsistent

I’ve observed that we’re inconsistent when we judge different persuasive tactics. Our judgments about the rightness or wrongness of a particular persuasive technique tend to break down under closer scrutiny. Consider the following observations:

Effectiveness

Persuasion, and even control, are subjective things. What seduces one person might be laughable to someone else. This makes it difficult to argue that a particular tactic is right or wrong when the effectiveness is dependent on the person being influenced. If one person is influenced by the presence of testimonials on a page (an influence tactic known as social proof), and simply changing a word in the copy is enough to influence another person’s behavior, how can we say that one tactic is unethical but the other is not? Both of these intentional decisions influenced someone’s behavior. You might even argue that the person was being manipulated in both cases.

If you take this stance against persuasion tactics because they influence or remove choice, then you’re placing a line somewhere very far to the left, seeking a purely objective representation of information. I’m not sure this “objective” presentation even exists. All design influences behavior, even if we’re not intentional about the desired behaviors. The ethical line we draw between trying not to influence, influencing, and manipulation seems to depend more on the person’s response than on the tactic used.

Application

The second kind of inconsistency I’ve seen when making ethical judgments about persuasive techniques has to do with how those techniques are applied. We condemn things like subliminal messaging but are then willing to undergo hypnosis to help us lose weight.

The same tactics we hate when used by a used car salesman, we praise when used by our leaders. In many areas of our lives, we want to be led along.

Consider basic social interactions. We learn through interactions and feedback how to tell a story that other people will enjoy and not be bored by. We learn which conversation-starters work and which backfire. We learn to speak clearly and with confidence. We learn that our words can hurt or help people. We learn that people have different personalities and we can’t interact in the same way with everyone. We learn how to interact in ways that will make people feel good about themselves. We learn simple rhetorical skills, such as how to use repetition for effect.

Through trial and error, observation, or instruction, we learn how to interact with other people. And in so doing, we’re learning social interactions that are really about inspiration, influence, and persuasion. We delight in people who can tell a good story or get us to open up about ourselves. Whether we’re aware of it or not, we’re attracted to these people who can lead us along. What we don’t like is when people use these same skills to manipulate or coerce us into doing things we later regret.

And it’s for this reason that I don’t think persuasion tactics are unethical. They are a necessary part of life. What is unethical is when and how they get applied.

A More Critical View of Ethics

If you agree that seduction techniques and persuasive tactics are neither good nor bad, you’re probably still bothered by numerous examples of unethical behavior—as we all should be! But let’s point the blame in the right direction.

Aside from the content of what we choose to work on, what other considerations are there?

This is still early and formative thinking, but I share these thoughts to advance our discussion of ethics and persuasion. In addition to your personal convictions about the domain you’re working in (marketing cigarettes, selling toys to children, recommending a retirement savings program), consider these two dimensions:

- The willingness of a person to engage in the behavior change. This can range from, “I want to do this!” (save money for retirement, lose weight) to, “Meh. I don’t really care.” (signing up for a new site) to, “I don’t want to do this!” (being compelled to purchase something we don’t want).

- The tacit awareness of an agreement, as suggested by the influencing party. This ranges from explicit (retail stores want to sell you something, schools want to educate), to implicit (watching an emotionally charged movie may change your viewpoints) to covert (subliminal messages).

Much remains to be discussed in this area, but I feel like this is a step toward a more coherent way to make ethical judgments. I offer up these thoughts not as a conclusion, but as work-in-progress, and a challenge for everyone to take the topic of ethics seriously. Let’s find and advance a thoughtful perspective that is consistent in all cases and, in the process, help make the world a better place.

Stephen P. Anderson

Stephen P. Anderson is a speaker and consultant based out of Dallas, Texas. He spends unhealthy amounts of time thinking about design, psychology and leading intrapreneurial teams—topics he frequently speaks about at national and international events.

Stephen recently published the Mental Notes card deck, a tool to help businesses use psychology to design better experiences. He’s also writing a book on "Seductive Interactions" that will explore this topic of psychology and design in more detail.

Prior to venturing out on his own, Stephen spent more than a decade building and leading teams of information architects, interaction designers and UI developers. He’s designed Web applications for businesses such as Nokia, Frito-Lay, Sabre Travel Network, and Chesapeake Energy as well as a number of smaller technology startups.

Stephen likes to believe that someday he’ll have the time to start blogging again at PoetPainter.com