This photograph captures how I feel at the start of a large project. With lists of requirements and all of the features, technologies, people, and processes, it’s difficult to remain focused on what’s important. It’s easy to lose sight of the desired outcome.

In 2002, working for a U.K. telecommunications company as a product manager, I was tasked with improving the UI for their digital television customers. This touched on every part of the business, from their call centers to IT. I soon discovered the service was causing dissatisfaction. Customers were leaving. A new UI wouldn’t cut it; a complete overhaul of the service was needed.

The company needed to start by understanding how bad the experience was for customers. They also needed to overcome their fear of change because everything they’d done before had been:

- overly complex

- riddled with bugs

- irritatingly slow

I needed to convince the company that this project was going to be different—different in that it focused on the users. My vision was to deliver an experience that was the opposite of what we’d done in the past by being simple, stable, and fast.

This vision became the guiding principle for every decision on the project. I knew the vision was working when on a weekly conference call, the project manager was telling me that an idea had been dropped because although it made the product simpler and possibly more stable, it didn’t make it faster. The stress fell away; the project was going in the right direction.

Previously, the company hemorrhaged money to technical and support costs with every new code release. This time when we released, our support call volume was negligible. We saved £3 million on that alone.

I didn’t know it at the time, but I had created an experience vision: a simple sentence expressing the core of the experience the user will have with the product, service, or site. I’ve since learned that having such focused vision is something successful companies have in common.

Characteristics of a Good Vision

Steve Jobs’ said Apple’s vision for the iPod was “to make it so simple that people would actually use it.” That vision works because it is:

- core – it expresses the core of the experience

- attainable – it’s within reach in the near future

- measurable – it’s a yardstick against which decisions are made

- emotional – it has meaning to, and connects with users

- communicable – it’s easy to understand, even when you’re not there

- memorable – it sticks in people’s mind

- specific – it’s tailor-made for the project

- user-focused – it talks from the user’s point of view

- practical – it’s pragmatic rather than aspirational or even inspirational

- clear – it uses plain language, not business-speak

Why Visions Work

A shared vision is the coordinating force behind many of the products and websites we love. They help us remain focused and to bring people together. They also:

- aid collaboration

- create a culture of shared ownership

- help us stay on track

- keep focused on who’s important: the users

- manage complexity

- mitigate risk

- hold together agile workflows

- build narrative continuity

There are some other surprising benefits:

Let designers do what they do best

Design processes are often represented in a linear fashion, but design has never been linear. The best design happens when designers have the freedom to explore and go off on tangents. A shared vision helps provide a reference point to come back to when exploring, much as design principles do. This enables design to work as it should: nonlinearly.

When I shared these thoughts with Jon Tan, fellow designer at Analog Coop, he confirmed this view. He described the creative process as like “circling a target,” around and around, sometimes getting nearer, other times farther away, before finally hitting the spot—like circles on a target rather than lines on a project plan.

Making designers more effective

The left-brain processes information sequentially, such as using information piece-by-piece to solve a math problem or a science experiment, working from the parts to the whole. This is how a project manager plans a project. But the right-brain processes intuitively. It gets to an answer without knowing the steps to get there. On a quiz, it uses a gut feeling as to which answers are correct, and it’s usually right. The right-brain works from the whole to the parts, much as a designer designs.

But that’s not the complete picture. We produce our best results when both sides of our brain work together. Project managers need to be creative. Designers need structure. For designers, structure should not inhibit exploration; micromanage a designer, and you’ll most likely manage the creativity out of the project. Loose boundaries, like design guidelines, work best in providing structure for designers. A shared vision gives the right balance of openness and structure, enabling design to flourish.

Minding the big picture

In Getting Real About Agile Design, Cennydd Bowles highlights that eliminating the “big design upfront” stage makes it harder for people on the project to mind the big picture. Agile moves fast, and as changes proliferate throughout the project the team can lose sight of the big picture, making them less effective. A vision preserves a focus on the big picture without the big design upfront. If you’re wondering how a vision fits into your agile project, think of user stories as the details, and a vision as the big picture.

Preserving consistency across channels

We’ve all experienced it: a company provides great service when you talk to them over the phone, but disastrous experiences in-store. Having a consistent experience across channels is really hard, and remains the biggest challenge for UX designers. Joe Lamantia, in his Beyond Findability presentation at the 2010 IA Summit, said, “As experiences span multiple media, channels, devices and formats, we need to look to narrative, interaction, emotional elements to sustain transition across channels and formats.” The vision sets the narrative to sustain the transition across channels.

Solving cross-channel transition starts with the experience vision, but doesn’t end there. Every vision needs a plan to deliver it. The experience strategy is that plan. I’ll discuss the experience strategy in my next article in UX Magazine.

Examples of Shared Visions

Here are some of my favorite visions:

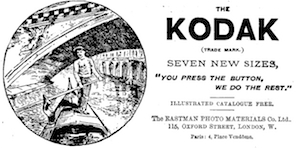

Kodak

You press the button, we do the rest.

I love this because it’s simple. It expresses the core of the experience.

Audi

Design, innovation and the joy of driving.

If you’ve driven an Audi, you’ll understand why this is such a great experience vision. This vision is simple, specific, attainable, and emotional.

Death Cab for Cutie

To write songs that make people feel that thing, like hairs standing on the back on their neck, that makes them want to hear it again.

I discovered this when listening to an interview with Ben Gibbard of the band Death Cab for Cutie. It demonstrates how a vision may already exist in the things that people say. Listen for:

- stories that you hear from more than one source

- stories with action detail

- stories that make complexity easier to understand

- stories with an outcome

Why Visions Fail

For every good vision, there’s a myriad of bad ones. In setting a vision that works, it helps to consider why visions fail:

- created upfront

- doesn’t express the core of the experience

- set too far in the future

- difficult to make decision against

- not simple

- lacks emotion

- fiction not fact

- tries to be perfect

- not shared, lacks buy-in

- set by the wrong people

- not championed

- not user-focused

Created upfront

Working as head of UX for a UK television service, I inherited the vision, “Always Simple and Complete.” The vague juxtaposition of “simple” (implying the need to reduce) and “complete” (implying the need to add) led to arguments in meetings. How could it be used to make a decision?

It turned out that the vision was set at the start of the project—a common reason visions fail. In order for a vision to be measurable, it needs to be specific to the project, the people on the project, the product, and the users.

Fiction not fact

It’s tempting in setting a vision to aim for the stars. But setting a vision so far in the future risks making it impossible to see the steps to get there, making the vision unattainable.

Trying to be perfect

Not all interactions people have with a product can be perfect. The vision needs to reflect imperfections for it to be realistic, specific and measurable. As Steve Baty points out in What’s an Experience Strategy, it’s okay for some components of the experience to be average or even mundane. What’s important is that the experience excels at the points that really matter to users. Making every interaction memorable might be too costly, time-consuming, or impractical.

Working as head of UX for another UK telecommunications company, I met with the managing director of their retail division. I presented to him a vision and UI designs for a new product. He paused and said, “I like it, but we can’t achieve this.” The next time I met with him, I presented an experience that was more attainable for the company. It wasn’t perfect, but it excelled where it mattered most to users, and still outdid competitors. No single moment in my career shaped more how I work and think. A vision must be credible, both for users and for the company.

Not shared

People work best together when they have a shared vision, but often organizational segmentation interferes. Department goals can conflict with project goals. Financial goals help the financial team but don’t guide others. Technical goals help the technical team but are unintelligible to others. And none of these are expressed in a way that helps the marketing, sales, or customer services teams. A vision for the experience is an effective way to overcoming organizational segmentation. The experience the user will have with the product is something that anyone can imagine. It provides a common ground where different departments can most easily meet. It’s not always easy, but I’ve yet to find a better common ground for interdisciplinary teams. It helps that it’s the right thing for the team to focus on because if we’re not designing for the users of the site, then who are we designing for?

No one to bang the drum

Even the best vision can fade over time. Someone to champion the vision, and keep it fresh in people’s minds, is essential. Without a champion, the vision can easily get lost in the complexity of a project. The role of champion usually starts with UX people. Finding the right person or people to take up this mantle helps ensure the vision continues to shine and prevents it from fading and failing over time.

Lack of buy-in

For a vision to work, people need to believe in it. Allowing them to collaborate in the creation of the vision builds belief. A vision created by isolated individuals, rather then collaboratively, can lack belief and buy-in. To avoid this pitfall, create the vision in a collaborative workshop. I’ll discuss how to create visions collaboratively in a future article in UX Magazine.

Review the company structure to find the right project sponsor—the person who’s footing the bill. Ensure the sponsor is involved in setting the vision, if possible. At a very minimum, conduct a stakeholder interview to understand the business requirements of the project. If you’re working with a large company, there may be a meetings culture. Stakeholders have very busy diaries. Get stakeholder meetings in people’s diaries as early as possible.

Undue focus on technology

Technology changes quickly, which makes it a poor target. Focusing on what’s technically possible is a mistake when creating a vision. The user doesn’t care how it works, just that it works. People’s behaviors make a much better target for design as they are much slower to change.

Without a Plan to Deliver It, a Vision Is Only Words

A vision will fail without a plan to deliver it. It’s in the tiniest details that the best user experiences happen. An experience strategy is a user-focused plan that details the changes needed to bring the vision to life. It covers every touchpoint the user has with the company or the product. I’ll discuss a framework for creating a vision in my next article in UX Magazine.

Credit for article images: Jason Koharik