Save

In 2009, interest in the capacity of games to solve real-world problems spontaneously began to erupt within general culture. This was an idea that a lot of people had been promoting for a some time through initiatives like Serious Games, Games for Health, and Games for Change, but their message had mostly flown under the public’s radar.

As a UX practitioner, I had long been fascinated with exploring how games could effect positive change in people and achieve things that would otherwise be difficult through conventional design. It was clear to me that the UX community could benefit from expanding its toolkit of competencies to include game design, and by gaining greater exposure to the innovative work being done in video games. So at first I was thrilled when a lot of people started to talk games—not moment too soon, I thought.

Then it started getting scary.

The current problem

All of a sudden, products labeled as being “games” have started to appear everywhere. Unfortunately, many of these products have shown an insufficient regard for the quality of the player experience. They’re too often designed first and foremost to serve their designers’ objectives, and not to be enjoyed for their gameplay. They contain none of the joy, fascination, and complexity that make games the beautiful interactions they are. In the worst cases, they demonstrate an impoverished, cynical, and exploitative view of games and of the innate human drive to play.

Take, for example, the McNuggets Saucy Challenge, a Flash game on McDonald’s public website. The challenge in question is to dip your McNugget into six different sauces mirroring a pattern that increments by one sauce for every successful cycle (like Simon). When your memory inevitably falters, you’re invited to post your score—with McAdvertising—to Facebook as a prerequisite to being ranked on a leaderboard. This design is impoverished because it doesn’t offer meaningful play, only a simplistic retread of a game we’ve all seen before. It is cynical because it shows no regard for the legitimacy of play as a human endeavor. It is exploitative because it pursues self-serving ends that are disproportionate to the value of the gameplay experience it offers in return. I wish I could say that this example is an exception, but today it’s much closer to being the norm. It reflects a broader cultural bias that regards games as inherently trite and frivolous.

Then a graceless and overly memorable buzzword crashed into the culture: gamification. The name itself betrays the conceptual flaw of this fad, implying that experiences that are by their natures something other than games should just be dressed up to resemble them. And indeed, many implementations that fall under the gamification banner amount to little more than tacking points and leaderboards onto an underlying system that remains otherwise unchanged. These kinds of approaches will not survive because they do not value gameplay, so players will not value them.

Making matters worse, gamification also has a troublingly imprecise definition that seems to vary by the person using it. It has been applied to any game that attempts to achieve something—anything at all—beyond the boundaries of its own play space. It is terribly misleading to use the same word to characterize the successful work being done by designers like Ian Bogost, Scot Osterweil, and Jane McGonigal as well as the McNuggets game and similar follies. As the reach of the inevitable backlash grows, a mounting cultural skepticism of gamification threatens to stifle other, innovative applications of game design.

It’s all turned into a big mess.

Change is on the way

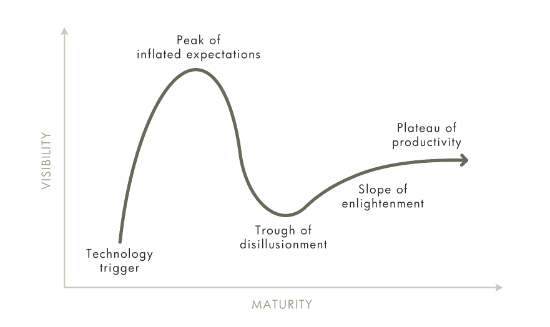

This ballooning enthusiasm around games closely mirrors Gartner’s hype cycle, which describes the typical pattern of adoption for a new technology. After initially arriving on the scene, its visibility increases quickly until it reaches a peak of inflated expectations, where people rush to the technology without a realistic strategy for putting it to effective use. Then a preponderance of early adopters discovers that, surprise surprise, the technology doesn’t deliver what they thought it would, and the hype collapses into a trough of disillusionment. As of early 2012, I believe that the hype cycle for games has crested and is plunging headlong toward this low point.

The good news is that after bottoming out, the cycle turns upward again. People start to discover and embrace best practices for using the technology, more success stories start to emerge, and it eventually finds productive mainstream adoption. So for games, the best policy at this point is to start moving toward a post-hype discussion of how they can most effectively achieve great things in the real world.

Here’s one of the fundamental insights that I believe will come out of that discussion: designers who are creating games must be centrally concerned with the quality of the player experience. That is, after all, the reason why people are drawn to games in the first place. It’s important to realize that there’s an innate selfishness to gameplay. People don’t play games out of loyalty to a brand or because they want to solve world hunger. They play because they value the experience. Trading off enjoyable gameplay in service of external objectives is always self-defeating.

I believe that UX designers are well positioned to play a significant role in developing more successful implementations of games that are designed first to engage and delight people, while also achieving real-world objectives. User-centered design is closely related to the player-centric thinking that’s common to all good game experiences. I’d love to see a substantial community of UX designers attending conferences like Games for Health, Games for Change and Games, Learning, and Society to learn, connect, and introduce a UX point of view. You could get started today by checking to see whether the International Game Developer’s Association has an active chapter in your area and sitting in on their meetings.

Another insight: to create high-quality player experiences, UX designers must develop a true competency with game design. While we have a lot of other skills that can translate well, game design is a robust practice in its own right, and much of it turns our usual ways of thinking upside down. Operating successfully in the games domain means learning an entirely new set of competencies and gaining experience putting them into practice. My previous article on the elements of player experience can serve as an initial orientation, and I’ve dedicated the largest portion of my upcoming book to the theory, skills, and practices that UX designers need to adopt to design successful game experiences. Critical books on game design that are not specific to UX practitioners include The Art of Game Design by Jesse Schell, Rules of Play by Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman, and A Theory of Fun for Game Design by Raph Koster.

Game on

Games present great new opportunities to UX designers, the limits of which are set only by the extent of our own imagination and creativity. We can also bring a unique perspective to games that can give rise to fresh approaches. At the same time, we must take on a new set of responsibilities to support experiences that engage, excite, and entertain. Games have an obligation to their players’ sense of active enjoyment that goes beyond what UX designers normally need to deliver. That’s also precisely the thing that makes them so interesting.

John Ferrara

John Ferrara has worked in in user experience design since 1999, designing interfaces for websites, desktop applications, and video games. Since 2006 he's been with Vanguard, and before that did significant work for Unisys and General Electric. He's been a forceful advocate for closer connections between UX and game design at the IA Summit, EuroIA, and Games for Health. He’s the author of the new book Playful Design: Creating Game Experiences in Everyday Interfaces, published by Rosenfeld Media. His nutrition education game Fitter Critters was a top prizewinner in the Apps For Healthy Kids contest, sponsored by Michelle Obama's Let's Move! campaign. Before entering the professional world, he earned bachelor's and master's degrees in communications. Feel free to follow John on Twitter at @PlayfulDesign.