Save

We tend to look through language and not realize how much power language has.

— Deborah Tannen , American author and professor of linguistics

Language matters for understanding humans.

If you are a UX researcher reading this article, you probably agree with this statement. As a UX researcher who’s passionate about languages, I took it one step further and wrote an article about why learning languages can help you become a better UX professional.

What we can easily agree on is that language can shape the way we think. It can bring all sorts of associations to mind, some of them are positive, and some are much less. That’s why we sometimes need to reframe a word or two to associate it with something a bit more positive.

Here’s why it matters to us, UX researchers, and to the development of our professional field. A few months ago I attended a virtual meetup with Louis Rosenfeld on his field of expertise — information architecture. It was fascinating and I’ve learned a lot in that session. I also had an “Aha!” moment at the end of it.

At the Q&A session, someone asked Louis Rosenfeld — “How can we convince stakeholders to use more research in our design decisions?”. His response was thought-provoking. He said, “We don’t necessarily have to call it research. In some cases, the word ‘audit’ could be better”.

That made me reflect on the many occasions where I saw different people reacting to the word “research”, not with the most positive expression. It was more along the lines of “we don’t have time for this” or “it’s unnecessary”. It made me realize that the word “research”, at least in a design/industry context, can sometimes work against us as UX research professionals.

Even though there’s a lot more buy-in for UX research according to a recent User Interviews study, there’s still a need for advocacy. On top of that, many of us, UX researchers, are proud of what we do so it’s hard to let go of the word “research”. However, simplifying our lingo is low-hanging fruit in bringing more clarity to what we do as UX researchers. After all, we’re helping design and product professionals make decisions, and we want to be viewed this way.

What’s so problematic with the word “research”?

There could be many reasons why the word “research” could sound problematic to people. I’ll mention five reasons that came to mind:

- It sounds academic — In a world where most people only heard the word “research” in academia, the association with the academic “ivory tower” is almost immediate. That could lead someone to think that doing research is for academics only, and it has no place in the industry. Sadly, this is especially true if your main stakeholders see academics as elitists and disconnected people.

- It sounds time-consuming and expensive — I guess a lot of it has to do with the first point I mentioned. The logic some people use is “If academics spend years on research that needs large budgets, it’s because they can, but we don’t have this luxury in the industry”.

- People confuse market and UX research — Some people we work with are very familiar with marketing research, meaning, big numbers. To them, a usability study with 10 participants doesn’t sound robust because they compare it to something else that’s not tackling the same problem. So, even if we can prove to these people we can do research fast, it’s not the type of research they know and are comfortable with.

- It sounds like a cost center to business managers— This one is important for dealing with any business. People who haven’t learned about the return on research (I think the 1:10:100 ratio is the best example) think research means cost. If you understand the potential return, it’s easy to explain why this assumption is flawed. Research is a way to cut costs by avoiding developing products with usability issues. After all, in the business world, that’s what most people still care about.

- It sounds ambiguous — When you tell someone “I do research” without being more specific, it can mean different things to different people. Some people might imagine you in a white coat in a lab. Some might think you run marketing surveys, and some might think you play around with A/B tests. It all depends on whom you’re talking to. Therefore, being a bit more specific is key, and it requires using a different word instead of “research”.

If you’re continuing to read this article and you’re working in UX research, you know that all of this isn’t true. I don’t have to mention that remote usability testing cuts time and budget significantly. What I want you to take away from this article is how to reframe UX research using a more specific lingo.

This lingo could help promote our craft and make this whole field we call “UX research” sound a lot less scary and a lot more attractive to our present and future stakeholders. Remember, the idea here is to start creating a change in the perception of what we do as UX researchers. It will take time, but it’s worth trying, especially if you see yourself in this career for the medium-long run.

How to reframe what we do as UX researchers

As a starting point, let’s call everything we do “Research activities” instead of “Research” because we all know it’s a collection of different methods.

Reframing parts of these activities could lead to a much higher clarity among our stakeholders about what we do. We just have to find the right lingo to achieve this. I’m taking a stab at it by looking at where we are in our work process and the type of project we’re working on to come up with the right terminology.

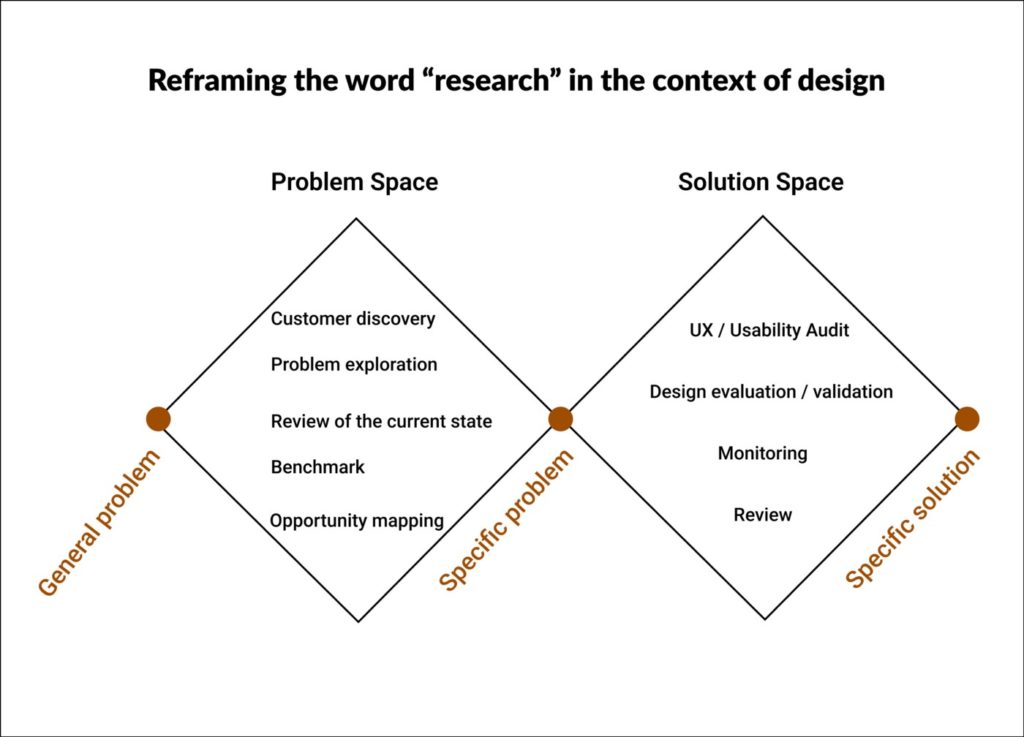

I know that many of us call anything we do in the problem space “Generative research” and anything in the solution space “Evaluative research”. These might be good for job postings for UX research positions, but I believe these aren’t good options to explain what we do to non-researchers. The reason? they still use the word “research”.

Let’s look at some alternatives. Bear in mind that what I suggest here isn’t set in stone. I’m sure there are organizations out there that come with their own great terminology to work around this problem. Also, languages evolve, and I’m sure that at some point in the near future we’ll have a few good industry examples to use.

What to use instead of “generative research”

Here, I’m referring to everything that is happening in the problem space. This is where we empathize with our customers and understand who they are, their mental models, and their paint point. The idea at this stage is to understand what the problem is, not to jump to solutions.

In this stage, it’s mostly product managers and business stakeholders you’re going to communicate with. They are interested in business opportunities, but they also don’t want to spend time on “research”.

Words you could use instead of research in the problem space:

- Customer Discovery — After going through a few synonyms I found this one to be very adequate here. It describes a situation where we have to discover something. It could be pain points, it could be mental models, information architecture, or a task sequence. If you want to dive deeper, take a look at this HBR two-pager.

- Problem exploration — This one could work as well, especially if we’re delving into customer interviews, contextual inquiry, or field research. We’re exploring what the customer problems are, and what causes them.

- Benchmark/review of the current state — If you’re talking about an existing website or mobile app that you need to analyze and see what doesn’t work so you can improve it, these terms could work. Benchmark could work very well if you are intending to come up with a solution and compare it to the current state.

- Opportunity mapping — If you’d like to do experience mapping or customer journey mapping, these are terms that not everyone is familiar with. However, if you frame it as an “Opportunity mapping” you might get a better reaction. The goal of journey mapping exercises is to find gaps and opportunities, so why not present it this way?

What to use instead of “evaluative research”

Here, I’m referring to the solution space. You’ve identified the problem, and you are starting to come up with solutions. These solutions need to be evaluated or validated by actual potential users.

However, if you present this process using the word “research”, you are risking falling into a trap since your audience is engineering and product people. They could say something such as “We need to launch this feature fast, we don’t have time for research”.

Here’s what you can say instead:

- UX/Usability audit — This one could work for both live features and features that are still in the design process. It almost makes it sound like a QA test that’s very common in the world of engineering. It’s more likely to fit an engineering mental model and make it seen as something that doesn’t delay the process and that is just part of it.

- Design evaluation/validation — This could work more specifically for work in progress

- Monitoring/review — This could work for live features that have UX metricsattached to them. Presenting it this way in a world of business where it’s all about the metrics is a big plus.

The image below summarizes all the terms you can use instead of “research” in both the problem and the solution spaces.

Conclusion

As I mentioned at the beginning of this article, UX researchers aren’t academic researchers. We don’t write academic papers or a thesis for school. We’re helping designers, product managers, and business stakeholders make decisions and we want the world to see us this way.

Changing the lingo around what “Research” means in our context is the means to achieve this goal. The list I provided in this article contains just a few suggestions, and I’m sure there are going to be more options available in the future. Terminologies evolve all the time, especially in the tech world.

Also, I’m aware of the fact that if English is not your mother tongue (or your work language) it can change the perception of the word “research” a lot. I’d love to hear if the same problem exists in other languages.

I’d also love to hear your impressions of this article, and know if you have additional suggestions as to how to reframe the word “Research”.

One thing for sure? Small steps lead to big changes. In the case of UX research, that small step could be reframing one word — research.

Yaron Cohen

Yaron is a multilingual professional in the field of UX research and digital strategy. At work, he enjoys helping companies innovate and improve their overall user experience. Outside work he enjoys music, long walks, and photography. Take a look at his portfolio at www.yaroncohen.com.

- Learning languages can help you become a better UX professional as it matters for understanding humans.

- There are different ways to reframe what UX researches do.

- What’s so problematic with the word “research”?

- It sounds academic

- It sounds time-consuming and expensive

- People confuse market and UX research

- It sounds like a cost center to business managers

- It sounds ambiguous

- What to use instead of “generative research”:

- Customer Discovery

- Problem exploration

- Benchmark/review of the current state

- Opportunity mapping

- What to use instead of “evaluative research”:

-

- UX/Usability audit

- Design evaluation/validation

- Monitoring/review

- UX researchers aren’t academic researchers so changing the lingo around what “Research” means in UX context is the means to achieve this goal.