Reflections on DSS Design Education Efforts

By Nadia Roumani, Natasha Bach, Thomas Both and Susie Chang

“To me, co-designing basically means partnership — working together,” said Havana Barksdale, a Columbus, OH high school senior. She had just participated as a co-designer with lived experience in a Stanford d.school Designing for Social Systems (DSS) workshop and design sprint, hosted in conjunction with the Columbus Foundation.

The d.school’s DSS Program strives to empower social sector leaders to be more human, effective, and creative in their work. In order to practice human-centered design practices and mindsets during our d.school DSS workshops, we invite participants to tackle a real challenge in teams. A critical characteristic of our workshops is bringing the voices of community members into the human-centered design process, so that social sector leaders are not designing in a vacuum but instead, grounding their work in the lived experiences of community members.

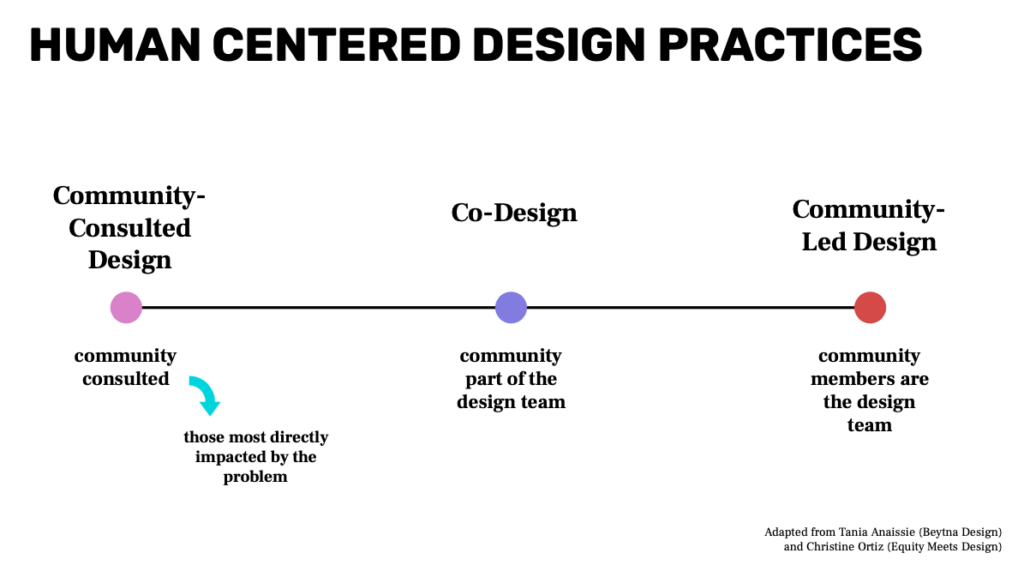

A human-centered design approach to tackling a challenge can take many forms. The following visual, adapted from Tania Anaissie (Beytna Design) and equityXdesign, provides three different practices along a spectrum.

As illustrated above, toward one end of the spectrum, community-consulted design is when designers working on a challenge consult those in the community who are most impacted by the problem at hand. In the middle, co-design, is when community members with lived experience are fully integrated into the design team — framing the challenge, conducting the design work, selecting the ideas to advance, and testing the ideas with stakeholders including those impacted by the problem. On the right, community-led design is when community members with lived experience are the design team, and design experts might provide support to community members who are leading the process. Co-design and community-led design are variations of practices often described as participatory design.

Previously the DSS program has engaged a community-consulted design approach in our educational workshops. In the past, we have done one of the following: invited community members with lived experience relevant to the topic to the Stanford campus, or brought workshop participants to community-based organizations to interview community members, and ground participants’ understanding in the human experience. In August 2020 we took a different approach.

In partnership with The Columbus Foundation, we led a workshop followed by four design sprints, in which we invited community members with relevant lived experience to join the design teams. We saw the opportunity and importance of incorporating community members with lived experience into design teams and thus, moved into a co-design approach.

We had individually participated in and facilitated participatory design work, but hadn’t integrated the practices into DSS workshops. However, with Tania Anaissie advising us on best practices of equitable design and co-design, and The Columbus Foundation’s commitment to co-designing with community members, we were well positioned to implement.

“We began co-design projects in Columbus in 2019 to support our work to improve community well-being,” explained Heather Tsavaris, Principal Consultant for community well-being at The Columbus Foundation, who encouraged introducing the approach in the workshop and sprints, and was instrumental in making it possible.

Heather’s team has worked with equity designers Tania Anaissie, Susie Wise and Chris Rudd over the previous year to design and deepen the practice of co-design by The Columbus Foundation.

“As we thought about how to influence the way our community solves problems, we were clear that the d.school’s excellence in teaching designing for social systems was the kind of design learning we wanted our social sector leaders to experience. We were thrilled when the d.school committed to embrace co-design for this workshop.”

How this new approach took shape

The workshop spanned 5 days and included 38 social sector leaders from across Columbus. For the workshop challenge, we partnered with the Columbus Metropolitan Library (CML) to explore how they could better support Columbus residents, ages 18–30 living in Central Columbus, in order to improve their access and preparedness for work, and address their life and learning needs. Participants were divided into 8 teams that each interviewed Columbus community residents in this demographic. Some of the individuals interviewed then joined the design teams for the remainder of the design challenge.

Following the workshop, in partnership with The Columbus Foundation, we hosted four week-long concurrent design sprints. The sprints were carried out in partnership with four Columbus-based organizations: The Women’s Fund of Central Ohio, The Columbus Metropolitan Housing Authority, Columbus City Schools (CCS), and the Columbus Metropolitan Library (CML).

Each sprint tackled a unique challenge that the organizational partner was facing or might be positioned to address. Each sprint included a design process facilitator, three to four workshop participants, a Columbus Foundation staffer, and approximately two community members with relevant lived experience.

How this structure came to life

For one of the four sprints that we ran after the workshop, the Columbus Metropolitan Library wanted to test the concept of the CREW — an idea that emerged from a co-design sprint led in the previous few months by The Columbus Foundation — that sought to understand why young people were not engaging with online learning. The concept of the program was as follows: a small cohort of students would meet (virtually) for a period each weekday with an adult mentor, to talk, listen and be heard. CREW aimed to engage and support high school students in their remote learning experience because so many students were not attending, and did not feel supported in remote schooling.

For this sprint, The Columbus Foundation invited back several high school students who had already been co-designers with the Foundation prior. Led by a d.school design process facilitator, co-designers — including students Havana and KB Abdullahi — joined four social sector practitioners and Foundation staff to tackle this challenge as a design team.

Having Havana and KB on the design team throughout the work meant that they were integral in reframing the challenge and ensured constant grounding in the students’ experience. They not only provided invaluable perspectives to the team’s understanding of the challenge, but they had equal power to determine what ideas were selected, how they were designed, and how they were tested. Students who participated as co-designers in both this and the CCS sprint were also able to reach more disengaged students who would be difficult to reach otherwise. Ultimately, the concept was launched as a pilot program in the fall of 2020.

We believe engaging the co-designers with lived experience in the workshop and sprints significantly impacted the proposed ideas and the team’s overall understanding and experience. Engaging community members in the entire process, rather than during one-time interviews, builds a solid foundation to collaboratively tackle complex challenges as a community.

Establishing practices to include co-designers with lived experience

In order to engage co-designers with lived experience into the workshop and sprints, we made some intentional changes to the workshop and sprint format design, and incorporated specific lessons and practices to support the practice of co-design. These changes built upon work and advice from Tania Anaissie, input and collaboration of DSS coaches and d.school colleagues, and learnings from The Columbus Foundation’s co-design experience.

Virtual format allows for remote collaboration and broader reach:

We did not choose to run the workshop virtually; the COVID-19 pandemic required us to do so. However, the virtual format greatly helped us incorporate a much wider group of community members and co-designers compared to when we held the workshop in person. The virtual format removed some of the physical and time constraints we often face when trying to engage end beneficiaries and stakeholders. The remote format also allowed us to reach a more diverse set of students. By going virtual we were able to expand our reach and engage people who lived anywhere in Columbus, Ohio — making it logistically easier to engage harder-to-reach community members. We were also able to engage community members in multiple sessions so they could be a more integral part of the design process, and in some cases participate as full team members. In the future, the virtual approach would allow us to also reach a more diverse set of participants in terms of race and socio-economic status as well, as we are able to invite a broader group of people when not dealing with physical convening constraints.

This experience showed us co-design was very possible and practical even with tighter time frames. While we believe an in-person engagement (for ideation, interviewing, or synthesis, say) may be ideal, the importance of including those with the most relevant lived experience (and potentially most affected by what’s created) outweighs the in-person advantages. Remote learning helps make that possible and at times, potentially more accessible.

Lay the groundwork well in advance:

We learned that it is important to start the planning process well in advance of the workshop and sprints because it requires time and effort to identify and invite well-suited co-designers to join the design work. Much of this groundwork was done through The Columbus Foundation’s existing relationships both with co-designers and with social sector leaders. In the past, co-designing wasn’t at the forefront of our mind when planning workshops and sprints, so it never felt possible as the dates approached. Once we made the mental shift, we were able to find the time required.

Be flexible with your process, tools, and timing:

In order to accommodate all co-designers, be ready to convene at times that work with everyone’s schedules. This can be difficult; however, flexibility is key to maximize inclusion of people with different life and time constraints. Also consider whether the way you are working is accessible to some community members. For example, some may not have access to the internet or digital devices. In Columbus, project teams adapted to different technology needs like connecting via phone calls if video calls were not possible.

Work with partners with deep ties in communities to engage potential co-designers with lived experience:

Since The Columbus Foundation had been doing co-design work in the community from 2019, including ramping up that work in advance of the DSS workshop in 2020, there was a sizeable cohort of individuals or lived experts who had experienced co-design and were glad to promote that experience within their networks. In addition, several nonprofit partners put out a call for community members to participate in the workshop. The existing person-to-person relationships and trust that The Columbus Foundation, The Columbus Metropolitan Housing Authority, and the Columbus Metropolitan Library had with some residents proved critical to identifying community members who were open to engaging with us in this process.

Provide an honorarium for co-designers’ time and expertise:

In the past we have provided an honorarium for all of our workshop and design sprint interviewees, often in the form of a gift card. But in order to acknowledge the larger contribution that co-designers were making to the workshop and sprints and their time commitment, we provided larger cash honorariums.

Ensure other design team members are aware of power dynamics and biases:

We needed to go beyond simply including relevant community members with lived experience, and also prepare the mindsets for all the teammates in the workshop and sprints. It was important for social sector leaders, who could be perceived to have more power when engaging other community members with lived experience, to recognize their power and privilege. By centering equity within our curriculum, we worked with participants to bring awareness to their personal lenses and the ways they influence others in the challenge with their beliefs and approach. As one example, we had participants complete a Paseo exercise (based on work of the School Reform Initiative) to help identify possible biases, and increase their awareness of current and potential power dynamics.

Put the challenge into historical context:

When launching the workshop challenge, we also placed the challenge into a broader historical context to help participants better understand any underlying systemic issues. This context was created through conversations with partners in advance and our own literature research. The presentation of this historical context was followed by a robust conversation among the workshop cohort and in the design sprint teams, to expand the breadth and nuance of the context. Providing historical context ensures that the team does not place blame on the end beneficiary, but helps participants understand the systemic issues and root causes that have led to the current situation.

Reflections from Co-designing Community Members on Their Experience

We asked some of the participants of the sprints to share their experience of the process. We’ve shared this in the following sections to emphasize, particularly, the personal impact of the approach.

Co-designers felt the impact of collaboratively designing in this way. For high school senior KB, who participated alongside Havana in both the workshop challenge and the Columbus City School sprint, being brought into the design process was transformational. He explained that he and many of his peers have often thought that his school district treated students like they’re “just a number for four years.” When he participated in the design sprint, he felt like the participants actually wanted to hear his views — even if it meant throwing their own ideas and preconceived notions out the window:

“If what you say or think tears apart what [the designers have] been working on, they’re fine with that,” he said. “They don’t know the experiences of the students and they acknowledge that.”

Havana also felt like her perspective as a student was heard:

“It was the first time my opinion and feelings were considered when it comes to school,” she said. “Even though we’re students our opinions weren’t less valued. They were actually more valued because we’re in the online learning environment so we know firsthand what we’re talking about.”

At the end of the workshop, Havana said that she “used to think that students had no voice in terms of school and how it operates.” With her experience participating as a co-designer, she felt that she was given a real opportunity to share her views and that “people actually want to know what [students] have to say about things.”

KB also felt like the other participants were really open to hearing new ideas, creating a supportive environment in the process:

“You’re not just getting a participation trophy for being there. Your opinions are valued — you’re not seen as an unequal but an equal. Your ideas matter just as much.”

Yet the students also felt the pressure of their role. Havana said that as “an advocate for my peers,” she felt responsible for doing well and providing good feedback to improve the situation for all students.

KB felt similarly, noting that he is only one person, so while he can speak to his own experiences and perhaps that of some of his peers, he knows that different people have different struggles.

Despite the overall excitement and pride KB and Havana felt, there was still some skepticism. He now has a better understanding of the “inner workings” of the school district operations, but he’s still not convinced of the district’s “openness to new ideas.”

Havana was also worried about the work translating into action from the schools and superintendents. But since the workshop concluded, she has been part of a team developing and testing the prototype with the Columbus School District.

Social Sector Leaders Reflect on Collaborating with co-designers

The DSS workshop and sprint participants also commented on the impact of working and building alongside co-designers with lived experience. Although they are all social sector leaders who are not new to engaging community members, for the majority of them, this approach of working with community members on their project teams to tackle the challenges together, was a new way of engaging community members with lived experience.

“The notion that we would involve the end user in the entire experience was life-changing for me,” said Donna Zuiderweg of the Columbus Metropolitan Library. “From a nonprofit perspective, my experience has been that we try to intuitively figure out what customers want or need, but I hadn’t really experienced it where we so fully engaged the end user in the development and testing of the program or solution to the challenge.”

“Bringing people in can be time-consuming and a more costly way to do our work, and that’s one of the biggest things that has held us back from doing so in the past,” said Kelley Griesmer, of the Women’s Fund. But her experience participating in the workshop demonstrated the importance of making that happen:

“[As a trained lawyer,] I had been conditioned to look for certain comments or things I needed to prove a case. So often we have an idea and we look for proof that we’re right. Co-designing is the complete opposite,” she said. “I realized that no matter how hard I’ve attempted to learn, if you haven’t experienced what [your end user] is experiencing, then you’re not an expert.”

Sonja Nelson, Vice President of Resident Initiatives at the Columbus Metropolitan Housing Authority, spoke about engaging co-designers going through their own self-sufficiency journeys after having gone through that herself earlier in life:

“The one thing I thought was missing in my own journey was my voice. Seeing that there’s a whole movement in activating that voice was great. I was in such awe the entire time.”

But she also felt a burden after gaining these insights from community members. “Once you ask a group of people how they feel and get their insight, you now have the responsibility of following through on that,” Sonja said. “When you’re part of a system, that makes it even harder. We know that we won’t always be able to immediately deliver on their expectations — so how do we address these diverse opinions and insights while not letting anyone down?”

In a post-workshop survey, another participant said:

“I’m feeling empowered to advocate for the importance of regularly engaging our constituencies for feedback and brainstorming; to value the peculiar and listen to outliers; and to consistently hold myself and my team accountable to an equity lens.”

The process of inviting in co-designers with lived experience and truly listening to and incorporating their voices and views enabled the participants to reframe the challenge. Rather than devise solutions based on their own biases and assumptions, the participants had the benefit of receiving input from the precise individuals they hope and seek to serve.

Following the workshop, The Columbus Foundation is continuing both financial and technical support for those who want to build co-design processes into their work and is continuing to build out its own internal co-design practice and capability. We also heard from workshop participants, such as Sonja, who is integrating a practice of co-designing with community members with lived experience into her organization. She realized that one of their existing engagement plans that was intended to build better relations with residents “didn’t even scratch the surface for true engagement and interaction.” She is now going back to the drawing board to make the process truly engaging for the community members it will impact the most.

On-going DSS work to integrate co-design

We at the d.school’s DSS program hope that co-design will help practitioners re-engage their communities in a different way, and encourage them to explore new ways of addressing the issues and challenges they face in their jobs. Or, put another way, the work is best done with members of the community as part of the team. Crucially, we think co-design can help push back against the tendency to leap to solutions. For community engagement in design to really work though, we need to not just interview community members, but also ensure we include them in the problem framing and problem solving piece as well. In our view, this is the best way to ensure that we are solving for the right problem, not just the problem we think exists.

We believe this experience demonstrated how powerful this approach can be — provided that you are able to set the context and deliver both with and for communities. But as we saw from KB and Havana’s feedback, this kind of work also raises expectations. So while it may help build buy-in, trust, and better-founded results, we urge organizations to be mindful: beware of using this approach without the ability to follow through. In our view, if you don’t have the capacity, intent, or political will to act upon the information and insights, applying this approach may actually do more harm than good. Furthermore, organizations may be well-served to gain a handle on a design process before moving fully to a co-design or community-led approach. As shown in the spectrum of human-centered design practices, you can continue to build toward more community ownership, and be at different places on the spectrum.

Designing for Social Systems continues to prioritize co-design and integrate those with lived experience in our current and future engagements.