Face it, all your projects are eventually going to die and you haven’t even designed the ending. In a world flooded with new apps, services, and products can we really assume that the design we’re working on won’t be killed off in the evolutionary cycle of the next big thing? We blindly focus on creating a user experience for the onboarding and usage of a product or service and overlook the off-boarding.

Not only does this create waste and clutter in physical and digital service landscapes, it leaves the customer in a state of ambiguity that overlooks the importance the brain assigns to the end of an experience.

Our memories are captured through our senses into a working memory, which ascribes meaning to what we are experiencing. This working memory will be assembled somewhere in the prefrontal lobe of the brain. The brain will then dispose of distracting information from the memory, similar to file compression on a computer. This process also converts that short-term memory to a long-term memory.

Closure experiences need to be designed well, not left in limbo

In his book Thinking Fast and Slow, psychologist Daniel Kahneman reveals how we lay down memories in two modes: “our experiencing self” and “our remembering self.”

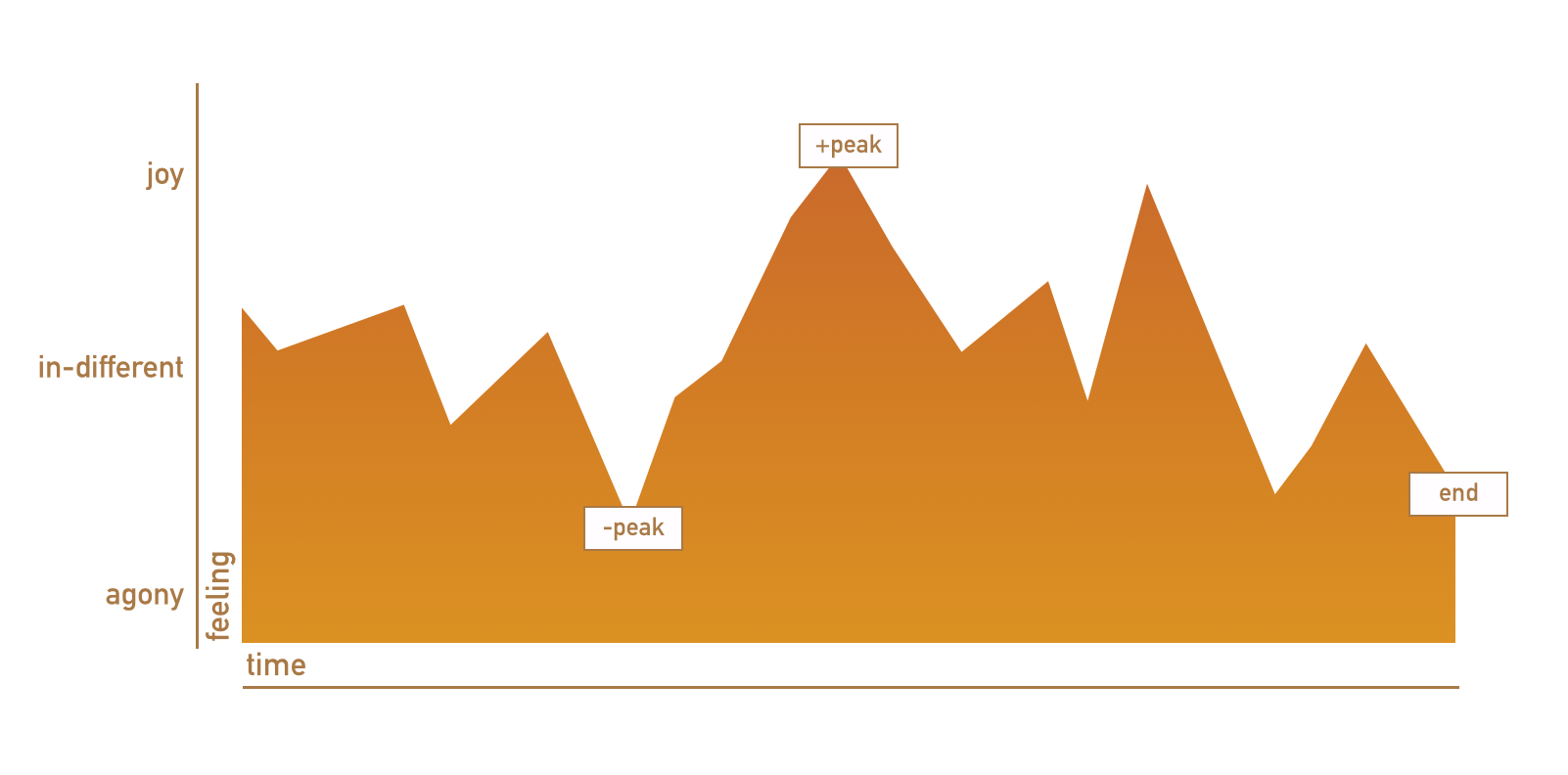

“The experiencing self is the one that answers the question: ‘Does it hurt now?’ The remembering self is the one that answers the question: ‘How was it, on the whole?’ Memories are all we get to keep from our experience of living, and the only perspective that we can adopt as we think about our lives is therefore that of the remembering self.” In this sense we remember experiences as “peaks” and “endings.”

Peak End Rule. Barbara Fredrickson and Daniel Kahneman, 1993

Peak End Rule

The second observation made by Daniel Kahneman is the Peak End Rule. He found that people judge experiences based on their peak (an intense moment of the experience) and at their end, rather than a total flat average of the experience. The duration of the experience has no bearing on the experience over all.

Reflecting on our own industry it seems we very much focus on designing for the Experiencing Self, hoping that the Remembering Self will recall repeated good experiences. This is confirmed by a quick search online for “Peak End Rule and user experience,” which brings up lots of results with the usual summarization of “you must deliver a good service all the time as this will result in the end being really good for the user.” The thrust of these arguments focuses on repeated peaks as the fore-bearer of a good ending—hence the persisting the denial of considered endings. We need to be wary of mislabeling task completion as an ending: real endings don’t happen again.

Need For Cognitive Closure

Another psychological notion that supports the power of designing closure experiences the Need For Cognitive Closure (NFCC). This is the tendency for humans to seek out firm answers and to avoid ambiguity or “Seizing and Freezing” as Arie Kruglanski—the author of the theory and a social psychologist—puts it.

In society we use sophisticated, well-oiled techniques for the on-boarding and usage stages of the customer life cycle. Driven by an economy wanting the next sale, making promises that may or may not fulfill emotional and spiritual needs. Satisfying what Maslow would class as self-actualization on his hierarchy of needs.

This contrasts the techniques utilized in the off-boarding phase or the closure experience of the customer life cycle. These techniques are often brutal, primitive, and occasionally guilt inducing. The lie that is implicit in the acceptance T&Cs of digital products (“I have read and agreed to these Terms & Conditions”), the threat relating to the potentially hazardous chemicals contained in products that we may have to dispose of, and the ambiguity in the ownership of financial service products.

In applying Closure Experiences to your design process you should aim for an increase in self-reflection by the user at the end of their experience, invoking any relevant personal responsibility required and raising the awareness of the moment of transformation between usage and off-boarding.

In the digital space that might mean making people conscious of the lingering nature of their online data. With products it might mean talking to the consumer about the afterlife of a product as a narrative rather than a confusing jumble of chemical and material terms on the back of the product packaging. In financial services it might mean considering maturity up front as, for example, there is an interval of decades before most pensions are fulfilled.

Closure experiences need to be designed well. Not left in limbo. As the evidence suggests from these examples of psychological research, the way we experience endings is important. First impressions last temporarily. Closure experiences are permanent, so let’s start designing them.