Listening to citizens is becoming very trendy in government land, here in the Netherlands. At least, that’s what I read on my LinkedIn feed from civil servants colleagues. But wanting to do so is not the same as really doing so. Listening to citizens and then ensuring that something is done with the insights that you get is quite difficult.

To do this, listening to citizens should not be incidental, but standard. Policy and its implementation should be based on it. In this article, you will find a start on how you can professionally approach this ‘listening to citizens’ in your organization by making good standards.

I have written about a few of these things before. I will link to them so you can use this article as a starting point to continue reading about practical examples or experiments. A lot of these will link to blogs in Dutch. Please reach out to me if you have any questions or would like to discuss this topic.

The feedback loop

I started working at the National ombudsman in May 2021. I joined them because I wanted to research how you can set up a feedback loop between citizens, government counters, and policy in an organization. At the ombudsman this feedback loop is small, at government organizations it’s larger and more massive.

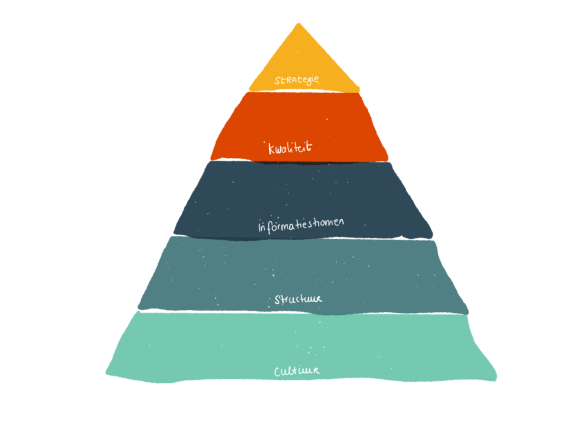

In the last few weeks, I analyzed how you can set up this feedback loop professionally. I discovered that different perspectives are involved that build up on each other, somewhat like a pyramid.

It naturally starts with a good conversation and getting to know the citizen. However, this does not guarantee that the context of people is leading in the making of government systems and policies. For this, we have to approach it more professionally.

This can be done by investing in a strategy, quality, information flows, structure, and culture.

These five parts need each other and are each other’s foundations. That’s why I put them in a pyramid. If you invest in one, it will affect another layer. I’ll go through them one by one.

Strategy

Why do we want to listen to citizens? And what do we do with what they tell us? This is of course where it starts.

The ultimate goal, if you ask me, is to make government policies and services that are good for people. And continuously manage them with care. This does not mean that everyone is allowed and able to do everything. We can and should maintain or set limits in a humane and understandable way.

I have the most experience in organizations that provide services for citizens. In this context, what are government services that are good for people? Lou Downe writes in Good services 15 principles for good government services. In an earlier essay, I wrote: “It’s not about the website (or whatever form your government service takes) but about people.” People have a goal or they experience something, and as a government organization, you are a part of that. You are never the goal itself.

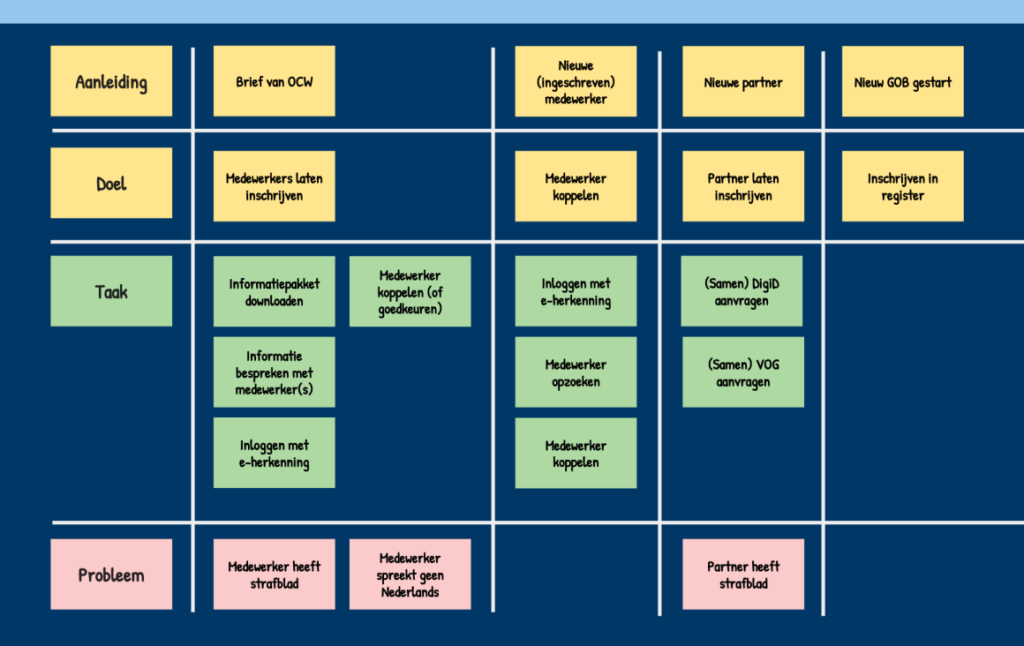

A useful starting point with this way of thinking is the exercise cause, goal and task. Looking at your services in this way immediately changes your view 180 degrees from the organizational perspective to the perspective of the person involved with your service.

What does this mean for the strategy of citizen research in your organization? All the research must lead to your organization gaining validated insight into the goals, tasks and reasons of citizens to interact with your service. And be able to place them in their context.

At the Education Executive Agency, I was part of the digital team where we also worked with a number of citizen researchers (or user researchers). We used the slogan of the British Government Digital Service: the strategy is delivery. Citizen research only works if you, together with all disciplines responsible for the service, make it so that the user actually achieves his goal. You test whether you have achieved this goal when the cycle is complete.

We also aim for this at the National Ombudsman. Despite all the good intentions of the government, what matters, in the end, is what citizens notice in their own day-to-day life.

An example. Refugees who come to the Netherlands to build a new life rarely speak Dutch, usually no English, and are sometimes even illiterate. Yet the government has a website that is incomprehensible to integrators themselves. From conversations we had with these people and their guides, we learned that they often used Google Translate to understand what was on a website. That’s why we came up with a built-in Google Translate function, with which you could read the site yourself in Arabic.

But someone tested the functionality and got a weird text back. That story quickly spread throughout the organization and the translation function did not materialize. Even though it would have really helped the people involved here. Our strategy to create services that help the user achieve their goals came to an end. Understanding how refugees use digital products did not lead to bold choices to create a website they can actually read.

This brings me to the second layer of the pyramid. Because to achieve these strategic goals, you need…

Quality

Most people are able to have a good conversation, and of course, it starts with that. But listening to citizens is also a profession. As an organization, you need validated insight into the context of the citizen. For this, you need a good quality of the citizen research carried out.

And the solution is actually quite simple: hire good people, train people, and make it a real job. Invest in methods and techniques. Use mixed methods: extract insights (qualitative) and validate them (quantitative). Examine what people say and what they do, often this is not the same. Dig deeper and put what you learn into context.

And reflect on how you work. On your own bias, yours, your teams, and the one of your organization. What assumptions do you have about the citizen? Are they justified, and how can you find out? What do they mean for the services you make? Discuss them and investigate them.

Example: you may have the feeling that it is ‘never enough’ for Groningen residents with earthquake damage. You try your best as government professionals but you always get the lid on the nose. Explore this idea. Is it true? And if it’s true, what could be behind it? What experiences may have led to this feeling for Groningen residents? With what you learn you can take a critical look at your work. How can the government build a bridge and what does this mean for how you make and offer your services?

Good quality is not only necessary in conducting research, but also in transferring the insights. What is the quality of the recommendations and what happens to them? When your research findings are noted — in whatever form — you are only halfway there. How you share them and with whom also determines what happens to them.

This is — by the way — one of the reasons why I am convinced of the value of permanent researchers in your organization and not (only) working with external research agencies who say goodbye after the insights have been delivered.

In order to deliver good quality, you need something crucial…

Information flows

Complaints and signals are received by the ombudsman about all kinds of subjects and organizations. You can’t imagine or something has come along. For example, we recently conducted research into a seance at a cemetery in Amersfoort.

A government organization usually does not look that broad. At DUO I did research into student financing and education. But not into mortgages or the labor market. From the perspective of the target group, these topics are related. As a government org, it is, therefore, necessary to bundle these topics if we want to know what students encounter and what they need from the government.

In fact, in the end, it is one relationship someone has with the government, and every contact they have has an impact on that relationship. Last year I visualized a month out of my own relationship with the government and I soon found myself in a huge relationship spaghetti. It’s complicated, yes, it is.

But let’s start slowly…

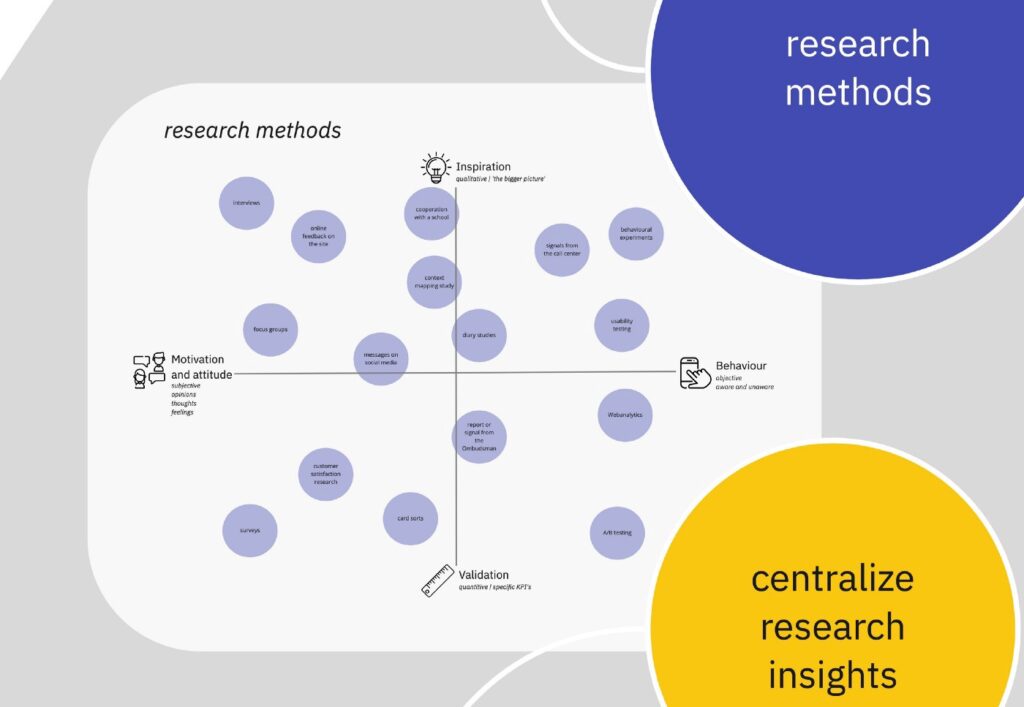

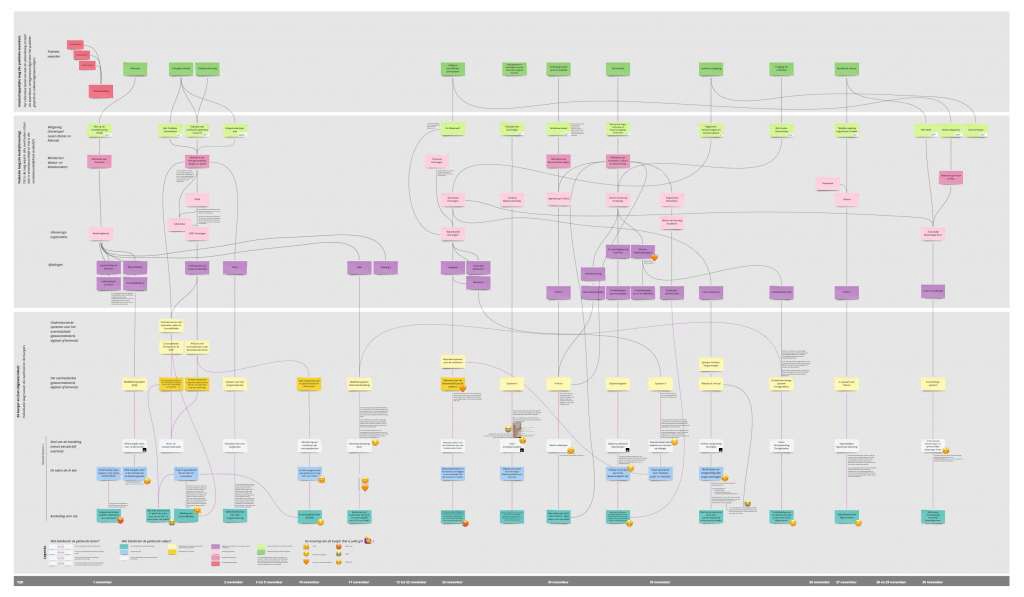

Even within one organization, it is difficult enough. Feedback from citizens seeps into the organization from all sides: via Instagram, Twitter, a feedback form on the website, via the customer contact center. We are increasingly conducting proactive research: user testing how specific applications are used, how letters are read, and all kinds of A/B tests. We measure behavior on government websites and there are all kinds of agencies or advisory bodies that conduct extensive research into interesting themes.

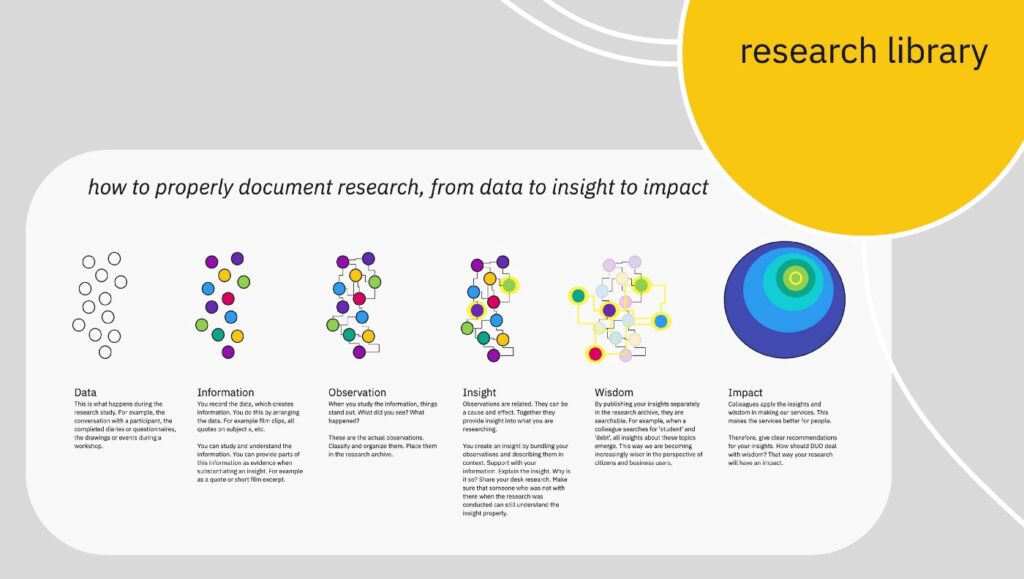

All this must come together in clear, searchable information flows. So that you can easily recognize patterns and see connections.

For example: at DUO we used a research archive to document all the research. You could search for a specific target group (MBO students) or application (MyDUO), but also for more abstract topics such as stress or feelings of guilt about student loans. We never did specific research into stress among students, but it came back in several studies. Because we tagged our observations and insights well in the archive, the flow of information told us about this angle. This was the reason to start a study specifically on students’ feelings of stress and guilt about the loan.

It also goes the other way. Not only the information flows inwards, but also outwards.

What I find so interesting about the ombudsman is that you can conduct broad investigations and you can present the findings to several organizations. The government has divided itself into chains, all separate parties that work together. For example, we have offered my research into the consequences of gas extraction to the Ministry of Economic Affairs, the Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, the National Coordinator Groningen, the Institute Mining Groningen, the five earthquake municipalities, and the province of Groningen. They all have a role in the solution.

If we want to listen professionally to citizens as a government, we must also properly organize information flows beyond our organizational boundaries. This has all kinds of snags, for example taking good account of the GDPR. But it is necessary if we as one government want to make services that are good for people and that suit their context.

You quickly run into all kinds of structural boundaries. So let’s quickly move on to the fourth tier of the pyramid.

Structure

What about ‘the governance’? Does it have to be one department? And how does it work together with other departments? Who does, and who doesn’t have to be involved or take ownership? A few times a year at DUO we discussed whether researchers should or should not be part of a development team, or whether they should work in between the teams. I’ve written many blogs about it and I don’t know the ideal structure yet.

What I do know is this: you cannot lock up insights about the citizen, it has to pass through your entire organization. It does not matter whether you organize it centrally or decentrally. It should work both ways.

Get close to teams that need to work with the insights or even become part of a team, and also organize continuous exchange throughout the organization. Work with departments, share knowledge and create a central place for all information. However, you structure it, ensure clear roles and responsibilities. Make clear agreements and facilitate cooperation and initiative as much as possible.

Citizen research is not something operational. Not only. Insights into the living environment of people are essential at every level.

They can be used very practical in implementation, but also with major strategic choices about new regulations, an important architecture choice, or extensive process change. At the start of a legislative process, you want insights about the citizen and the implementation, in the middle and at the end. That is why it is good that much more attention is being paid to the citizen’s perspective when making policy. And there should also simply be more jobs at the c-level in the field of citizen research and service design (see also point 2 about quality).

An example. In 2020, the new Education Act ‘More space for new schools’ came into effect. Two years earlier we were working on how DUO would implement this law. The draft version of the explanatory memorandum contained a passage that initiators of a new school first log in to DUO with their own personal digital identity (Digi-d) and work on their application. Later in the process, they can then convert this to a business account, when the school also takes on more concrete forms.

We prototyped how this would work and asked some people who were working on a school initiative to go through it. But they didn’t want to use their personal Digi-d to communicate with DUO, they wanted a business relationship right away. This was also better for DUO because the MyDUOs for citizens and schools are separated in the architecture. Such a ‘flip function’ of accounts meant quite a bit. In short: school leaders didn’t want it and it was expensive to build. Whoop, gone with that passage.

What I’m just trying to say: operational research or customer feedback management alone will not get you there. Early in the process and at a strategic level, you should start doing this type of strategic research.

This is all still within one organization. In order to function as a single government for the citizens, the structure must also help. Which structure helps with collaboration? There are already an infinite number of working groups and collaborations.

This is why it is important that within an organization there is also a central place where all the research comes together. From this central location, it is possible to collaborate with other organizations. A smart move that makes it easier to collaborate across structures and silos is to work in the open.

And then I come to the last. Perhaps the most important…

Culture

Yes, culture eats strategy for breakfast.

Everything I write above, above all, requires a listening culture. Space and help to reflect on our work together. Time and opportunities to listen to citizens, or to get their stories through from professional researchers. The desire to understand the other better and the insight that we are driven by assumptions, because yes, technology and policy are simply not neutral. A safe environment for giving and receiving feedback, also and precisely ‘upwards’.

Making something just so you can test it, maybe it’s a bit of a stretch, but that’s okay, because that’s how you learn, and then you start over with new knowledge. It’s the conviction that policy and implementation are never finished because your relationship with the citizen is never finished.

The best way to start with culture is to make this explicit and confront the other. At DUO I often organized meetings between civil servants and citizens, so that colleagues get to know, listen and experience how important it is to listen to the other person. I told the stories of students and refugees in all kinds of ways to increase such a culture.

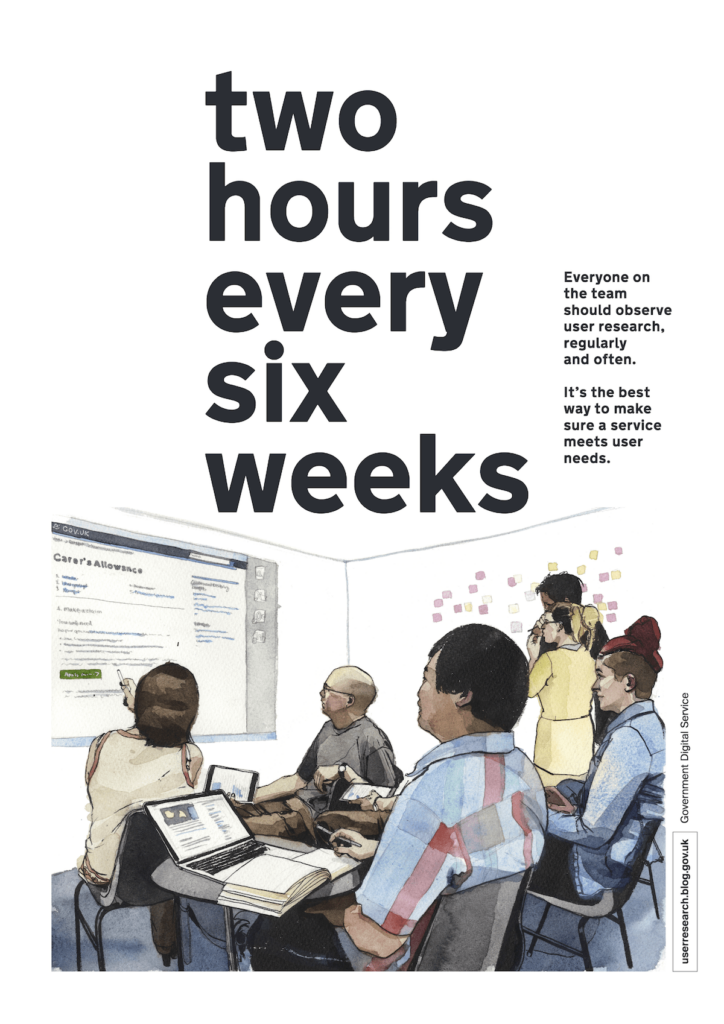

I did this following the example of Gov. uk, the British Government. They use the maxim that everyone who contributes in one way or another to the government service experiences research for 2 hours every 6 weeks. To experience and understand what people encounter, who they are, and what they need.

When I started in the government as a researcher and came back to the office with all kinds of stories about how things really went in the outside world, I often ran into walls. ‘What a lot of negative feedback, ‘that process is just the way it is, or ‘the website is almost finished, we can’t go back that far now’. If only my colleagues were more understanding earlier in the process, I sometimes thought, not knowing what adventure that assumption would tempt me into.