Analysis is a crucial part of any design process. Without it, it’s impossible to know if the right problem is being solved and if it is being solved in the right way. It’s also a part of the design process that tends to be neglected or ignored. When integrated tightly into design processes and teams, analysis can improve understanding of the problems that project teams are challenged to solve. It can also bring clarity to the detailed and often complex requirements that solutions must meet.

In his book, How Designers Think: The Design Process Demystified, Bryan Lawson describes the design process as being made up of three distinct but overlapping activities: analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

Analysis—the focus of this article—includes the activities of audience research, contextual inquiry, mapping of business processes, and documentation of requirements. Analysis covers any area that deals with understanding the problem and defining the desired outcomes. Analysis is about understanding the “why” and “what” of a project.

Synthesis is the part of the process where solutions are created and various design elements are pulled together into a working solution. Synthesis covers any area that deals with “how” things are done.

Evaluation is where judgments are made concerning the analysis and synthesis. Evaluation of the analysis gives direction and prioritizes requirements. Evaluation of synthesis exposes whether a proposed or completed solution is doing the job it’s intended to do.

When a design process uses a combination of each of these three elements, its chances for success are greatly improved, and makes it possible to be agile and comprehensive throughout a project cycle.

It’s All About Understanding

For this article, we will focus on analysis—not because it’s more important that the others, but because it’s a necessary component to the overall process and can be a good starting place for most teams. Analysis is the part of the process where things are broken down, taken apart, studied, and understood. The process of analysis helps a design team understand the problem they have been asked to solve.

On large projects, analysis is often performed by specialists who may have the title of “Business Analyst” or “Functional Analyst.” Their job is to determine the scope of the problem; identify business rules, processes, and constraints; and provide a document of requirements to the design team who will ultimately design and build a solution that meets the needs of the stakeholders.

Analysts use a variety of techniques and tools to develop this understanding, such as process analysis, statistical analysis, comparative analysis, functional analysis, and others. By looking at the problem critically and through different lenses, thorough analysis can bring to light important information that is necessary to develop an acceptable solution, and can help avoid costly and painful mistakes after a solution has been developed.

It’s Part of the Whole Process

While analysis is typically performed during the early phases of a project, it is also plays a critical role throughout the whole process. Whenever understanding is needed, thoughtful analysis can help provide it.

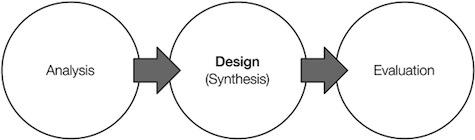

This diagram represents a common approach to the design process and is how most teams operate today:

At first glance, this seems like a reasonable, linear approach to a project. First, the project is analyzed, then designed, and finally the designs (or implemented solutions) are evaluated in order to test their effectiveness. The problem with this approach is that organizations tend to turn each of these steps into individual, isolated tasks. When this happens, it can be difficult to merge the work completed in each step into valuable, holistic solutions.

The Role of Analysis

Analysis shouldn’t be considered a separate phase to be completed before, or separate from, design; it’s an integrated and critical component of design. By acknowledging that design is the whole process and not just the synthesis portion of the process, we can start to break down the barriers that slow or stifle design work.

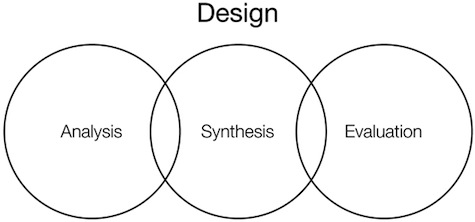

A more accurate diagram of the process shows the required overlap in these three phases of work:

In this model, the design stages overlap as design moves through the cycle. Once this cycle is complete, it yields a result. While this may seem like a good approach to design, it can feed the misapprehension that design is a beginning-to-end process—that once the analysis has been performed, it’s completely done, and the project can move on to the synthesis phase. The problem with this is that by considering the analysis phase complete, there’s an implied no-return policy on the research. What’s done is done. This is simply not true in actual practice, nor is it a viable, productive approach.

Each phase is integral to the entire design process; design isn’t a linear process where analysis comes first. Analysis is certainly a good place to start, but there’s no reason not to continue analyzing problems and their solutions throughout the whole course of a project.

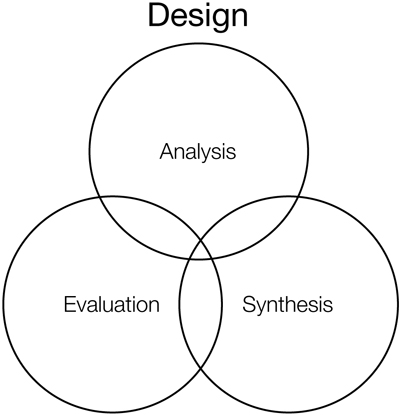

A holistic approach to design requires attention to all three areas during every phase of the project. If we spend too much effort in any single area, we put our potential for success at risk. If all we do is synthesize, we may end up with solutions that don’t solve the right problems—they’re just random stabs in the dark. If all we do is evaluation, we’ll know what isn’t working but won’t know why, and thus won’t have a solution to fix it. And if all we do is analysis, we’ll discover problems and plan endlessly, but we will never solve them.

The best design happens when analysis, synthesis, and evaluation receive equal and continuous focus. This means, by extension, that in projects with large teams, the best results happen when individuals responsible for each of these areas of design work closely together.

Working Together

It’s important that everyone working on a project is involved in the whole design process, not just the corner of it that coincides with their individual specialties.

Too often, those who perform analysis (analysts) and those who perform synthesis (designers and developers) are separated by organizational and cultural barriers that prevent the two from working closely together. Analysis is completed in one compartment and then handed off to the rest of the design team in the form of a written document or presentation. When the project goes awry, the analysts blame the designers, and the designers blame the analysts.

One of the reasons these barriers develop is that the very term design is misunderstood as a synonym for synthesis. Most people whose titles include the word “designer” are really synthesizers. They are best at making things, using their specialized craft to turn an idea into a reality. In this scenario, it’s no wonder that analysis often ends up in its own corporate silo or parallel business unit that has limited communication and collaboration with other participants in the design process.

Breaking down these barriers and developing a close working relationship between analysts and design/development will make the work of each stronger and more connected. Analysts who understand and work closely with the design team will provide better understanding and requirements, and will likely do it more efficiently. Designers who are involved in analysis activities will understand the problem, constraints, and details more accurately. This knowledge helps ensure that attempted designs are on-target.

Analysts have spent their career learning how to break things apart. They have learned how to take problem and accurately present all the individual components, requirements, and business needs to the designer. At larger corporations, analysts have been the critical link between the subject matter experts (who create the business requirements) and the design team. Analysts primarily do analysis, but that doesn’t mean they can’t suggest design ideas, or that they can’t contribute in meaningful ways to areas that are traditionally the domain of the designer.

In the same way, those who carry the title of “designer” and are specialists in synthesizing can also contribute to analysis. When designers are involved in analytical activities, they develop a better understanding of the problem, and can also aid in the presentation and formatting of information that can build knowledge for the whole team.

Getting More

There’s a place for analysis in every project. Regardless of the project’s size or scope, analysis is a key to ensuring you’re solving the right problems and delivering accurate results.

If you are neglecting analysis in your projects, you can get more by taking the time to effectively analyze the problem you are working with. Think before you do.

You can get more from analysis by making it a core part of your design process rather than just an activity performed before and after projects are started. Think of analysis as an ongoing activity rather than a document that handed off.

You can get more from analysis by breaking down organizational and cultural barriers that exist between analysts, designers, and developers. Involve designers and developers in analysis, and involve analysts in the design and development. The team and project will greatly benefit from improved understanding.

When you get more from analysis, you get more understanding. The more clarity and understanding you get, the better the chances are that the solutions you design and develop will effectively meet the needs of your stakeholders.