In the middle of the famous science fiction novel Foundation by Isaac Asimov is a mathematician, Hari Seldon, who predicted the imminent collapse of the intergalactic empire in which he lived, followed by a dark age lasting 30,000 years. However, he created a model according to which this grim period could be reduced by 30 times if all human knowledge were collected in the pages of the Encyclopedia Galactica. Hari was deemed dangerous, but he was believed: exiled to a distant uninhabited planet, the empire nevertheless gave him the resources to create a repository of human knowledge. Over the course of the book, we learn that the accumulation of knowledge was valuable not only for pure preservation of intellectual achievements; the high concentration of academics on the one hand and adventurers on the other allowed the creation of a high-tech state that became a center of influence and a thought leader on the fringes of the empire.

Repository of human knowledge… Sounds fascinating, right? Unless… Surely, most of you know how difficult it can sometimes be to use even well-documented knowledge:

You don‘t have to ruin an empire to realize how hard it is to reconstruct a civilization from documented knowledge — just start reading any internal enterprise documentation site.

And since our language is so ambiguous, LLM models don’t help solve this problem, either, which many business leaders already recognized. At least, LLM can’t help alone — but they can become a useful tool if you have a solid foundation.

In this essay, I want to play Asimov and imagine how enterprises could build their own digital Foundation. Or actually, that’s not quite right, because:

Building such a foundation is possible not only in sci-fi.

I will not tell you straight away about all the advantages that such a foundation — let’s call it a “digital backbone” — would deliver to businesses. That would just sound like something you hear every day (“We revolutionize the way how you…” etc.). In reality, work on a digital backbone is tedious and requires significant investment. But in the end, you might achieve a high ROI not only in financial terms (through cost reductions and new revenue streams) but also in harder-to-measure benefits, such as better employee engagement and even more fun at work.

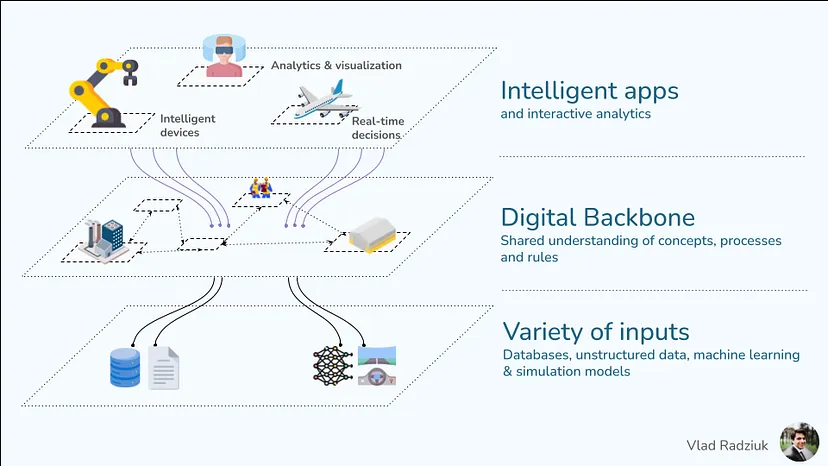

Many leaders are already familiar with the term “digital twin,” which is typically associated with the visual representation of real-life objects, like industrial machines. However, modern frameworks and technologies now make it possible to build digital twins for entire enterprises. And that is precisely the topic of my text. My goal is to provide a high-level guide for creating a digital backbone for an enterprise. Of course, any such guide will offer a highly simplified picture of reality — even an entire book wouldn’t be enough to cover it fully. Nevertheless, the right actions often begin with the right mental models in our minds. And my goal is exactly to present such a mental model.

Ambiguity, siloes, and other properties of human systems and societies

Many technological leaders, from my experience, tend to forget that IT organizations are sociotechnical systems. Taming the “socio” part is crucial for successful innovation management, as even great technological concepts can fail or be misused in a world populated by creatures with their own habits, mindsets, legacy, and cognitive biases.

As we recently saw, LLMs can (re)produce information, but they often fail to map the entities from the corporate databases to the concepts from real life. No wonder, as human languages are as ambiguous as human nature in general: the same words can have different meanings in different contexts; there is specialized jargon that is understood only by certain groups of people — e.g., professionals from the same occupation or industry. Just feeding an algorithm with more and more data will not help…

Another problem is that people always think in some sort of mental models. Our brain needs an approximation of reality — that is just our way of understanding the surroundings. British statistician George Box once said: “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” And here is the thing: the models which were created for a reason and were able to solve real-life problems at the beginning, became outdated with time and turned into a burden that skews our understanding of reality. Think of business dashboards, which in theory made total sense, but in reality show only post-mortem analytics for siloed contexts, with a temporal delay.

Information technologies: expectations vs. reality

According to the classical theory, the role of IT is not only to support and enable business operations but also to produce a competitive advantage. In reality, as organizations grow, maintenance of IT assets — e.g. software, data — becomes not trivial: information gets duplicated; the connection between developers and users gets lost; and the complexity of the system landscape becomes scary.

Under such circumstances, it is hard to not only produce innovations but even to support business continuity. Business rules, which build the core of the business, get lost in unreadable technical code, probably duplicated in multiple systems, in the worst case — in varying versions. Imagine a prospect that gets rejected as a customer via one channel (e.g. a form on a website), but later gets accepted via another channel (e.g. the call center) (jokes aside, that happened to me once in the context of employment). Given that businesses are obliged to comply with contractual obligations, deals, agreements, warranties, etc., it is unacceptable that the core rules are stored in a form not easily accessible to the majority of employees.

At least, that was the case in the era when English was not a programming language…

Everything is data nowadays; it is your task to make it useful

Disruptive Innovations are NOT breakthrough technologies that make good products better; rather, they are innovations that make products and services more accessible and affordable, thereby making them available to a larger population. — Christensen Institute

One of my favorite architectural styles is Bauhaus. The idea of Bauhaus — a German movement in the first half of the 20th century — was to merge art, craft, and technology to create innovative and practical designs that are relevant to modern society.

The Bauhaus taught the idea that form and function should be inseparably connected. Wait a second… What if we could apply this concept to the way we store information?

Remember how this article started? We were discussing corporate documentation and how easy it is to get lost in it. LLM models are not necessarily helpful: the principle “garbage in, garbage out” applies here as well. In the 2020s, we need to treat the documentation of our knowledge as an asset that will be accessed by AI agents.

Your documentation is no longer “just text” — it is a corpus that can be mined, synthesized with other texts, visualized, or used as a foundation for automated code generation. If you want that to be possible, you need to structure, annotate, and curate your docs. Form = Function.

Now that you know that texts can be handled as data, let me further broaden your horizon: business processes can also be treated as data. They can be visualized as diagrams, generated from a versioned code, and transformed into other text-based formats. The same applies to business rules. And as any other text, they can be — sorry for repeating myself — mined, synthesized with other texts, visualized, or used as a foundation for automated code generation.

The main achievement of generative AI is the blurring of borders between different media types. It was possible earlier to convert from text to pictures or from text to another text, but advances in LLMs now allow natural languages, such as English, to become the primary protocol for communicating with systems. And this needs to be reflected in the way how we manage our data, information, and knowledge.

Now, imagine a system — whether physical or logical — that allows formulating queries in English and getting results based on exact, reliable, up-to-date data. A system that synthesizes information from isolated data sources, such as databases, documentation storage, codebases, machine learning models, or simulation algorithms. A system that tracks changes and provides explanations for business decisions made in the past.

This is what a digital twin for an enterprise could look like. And with English being the primary protocol, now any decision maker or employee could access this information (with the right set of permissions of course).

When your business processes and rules are explicitly defined and have digital twins that enable human-friendly representations (e.g., visual ones), you can perform precise impact analysis. When you can combine data from various sources to gain insights, you break down silos and better understand what is happening. When your business language is formalized and your data is linked to real-life concepts, you overcome the barrier that separates business people from technical people.

Areas that would benefit the most from building such a system, include: Business process management, Manufacturing, Logistics, Customer experience, Risk management, Program portfolio management, and others.

Such a system would allow for real-time insights into the business operations; create better synergies between departments; enable more value delivered through IT, better planning and impact analysis, and exploration of new revenue streams.

A true Digital Backbone.

Sounds too good to be true, doesn’t it?

Realistic expectations and pragmatic approach

I dare say that technology is no longer the problem in the enterprise architecture field. There is a whole portfolio of Digital Open Standards, a collection of practices that any enterprise can implement. Semantic technologies, which allow you to give context to your data by linking it to real-life concepts (such as ontologies), have been around for decades. LLM models and frameworks to work with them are easily accessible. There are many products that claim they can build a digital backbone for your enterprise, but you could even do that with your own resources and open-source technologies.

For now, the technical details don’t matter. Let’s come to the human factors.

Platform

Building a digital backbone means introducing a new platform. And, like any other platform, it has to be maintained and invested in. It also means adding new tools, assigning people, and changing existing processes. This kind of platform is also special because it requires a decentralized foundation to be efficient. I will provide more details on that below.

Data has a cost

In the paper “Measuring The Value Of Information: An Asset Valuation Approach”, the authors came to the conclusion that information is a special kind of asset: the more it is used (and the more accurate it is), the higher its value.

The number of users and number of accesses to the data should be used to multiply the value of the information.

Which logically means that it doesn’t make any sense to collect data for the sake of collecting. The creation of data products has to be strictly case-driven.

Organizational and operational changes

Most likely, you will need to adapt your organizational structure. There are different approaches: from integrating IT specialists into domain teams to creating a federated team of knowledge owners. In any case:

- Your IT and non-tech specialists need to work more closely and be driven by use cases, rather than speaking different languages in isolation from each other.

- Your domain teams must be empowered to treat their data and knowledge as assets that they must curate and share with the rest of the organization.

The second point means the following:

Domains can’t operate effectively with project-based funding that fluctuates monthly. They need stable resources to build long-term capabilities and maintain their platforms. The most successful organizations implement what we call “domain-based capacity management” — providing baseline funding for core operations plus flexible capacity for specific initiatives. This hybrid model provides stability while maintaining agility. — Bjørn Broum, source.

Educational gap

From my experience, the most successful initiatives are born when engineers with developed soft skills collaborate with IT-savvy business people. I write more about that in one of my previous articles: “Software In the AI Era: Context, Business Expectations and Skills in Demand.” But too often I see technical people who are not willing to delve into the specifics of the business and not really interested in the business value of IT initiatives, as well as domain specialists resisting technological changes.

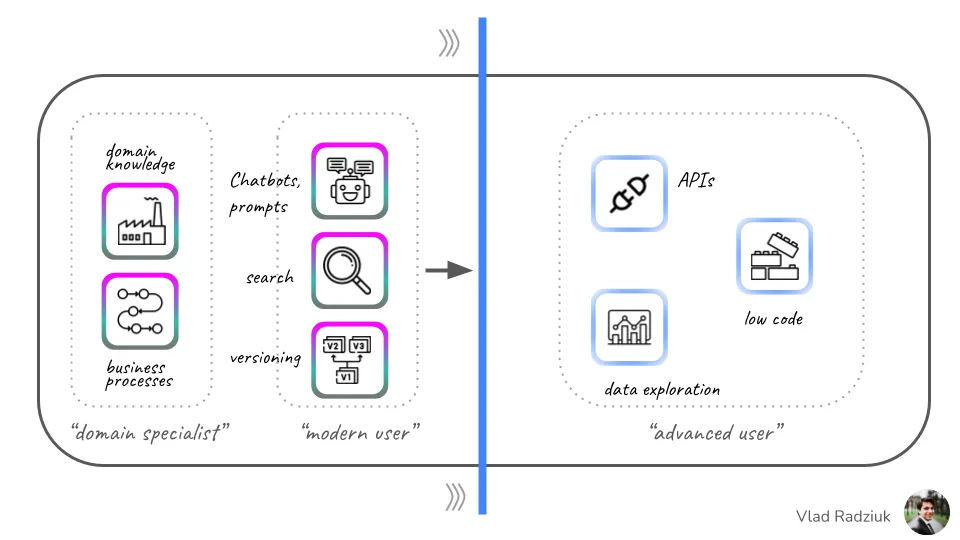

In this context, I want to remind you that for a modern user, it has become normal to use search engines, the versioning features of cloud collaboration platforms, or prompt-based AI interfaces. This provides a strong foundation for further upskilling. At the same time, in the realm of programming, there are techniques (e.g., domain-driven design) that allow for better collaboration with business users. Building a digital backbone will require adaptation from both sides.

The same goes for leadership roles. For many CTOs and CDOs, it is difficult to establish a link between IT initiatives and business value; they struggle to pitch their ideas in a way that is understood by the rest of the organization. Many business executives still believe that Enterprise Architecture frameworks are only for IT architects when in reality, they are meant for the entire enterprise.

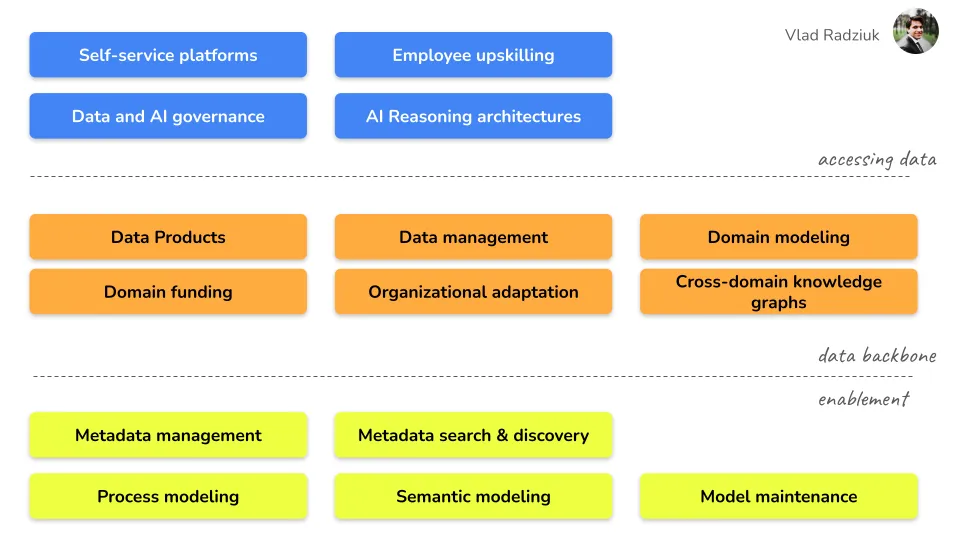

Capabilities

Below you will find a mindmap (not a process diagram, just a free form!) of capabilities that need to be developed in order to build a Digital Backbone.

What looks like a lot, is in fact — a lot!

Incremental work, federated way

If the idea of building a huge new platform scares you, you are completely justified in feeling that way. The good news is that you don’t have to build it all at once. Instead, approach it in a use-case-driven manner, focusing on one domain at a time. Then, implement a federated governance and access framework.

For this to happen, you need to have a strong “interface culture”: any product that you build, be it a software or a data product, needs to be talked to only via programmatic interfaces (the idea is not new — check out the Jeff Bezos’ API mandate from 2002).

Foundation was never about the knowledge preservation — it acted as a multiplier.

Coming back to our cozy sci-fi readers’ corner: what is the main idea of Asimov’s Foundation? For me, it’s about pragmatic politicians and merchants who know how to build successful enterprises on top of a strong knowledge foundation. Like them, business executives can see a digital backbone described above as a multiplier for their businesses, which can allow them to see their companies and their surroundings in full complexity. This can provide potential not only for cost-cutting but also for the creation of new revenue streams.

The better the digital backbone of your business, the higher the chance for your civilization to preserve itself and prosper.

The article originally appeared on Medium.

Featured image courtesy: Spencer Davis.