Save

In the Studio with Vinay Kumar Mysore, Design Researcher at Openbox:

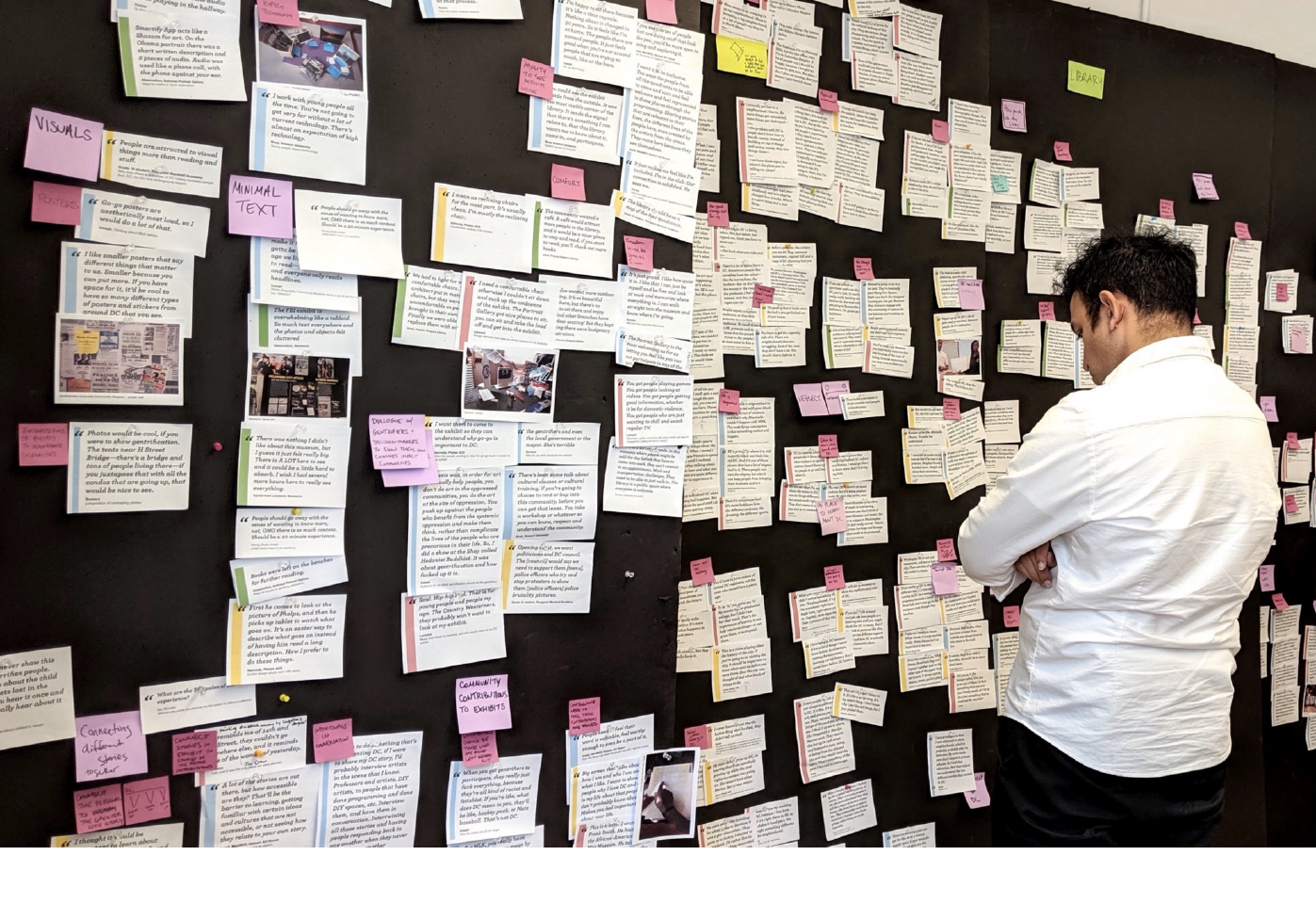

Understanding the lived experiences of communities is central to Openbox’s process. Community research in D.C. ranged from the experience of erasure in gentrifying neighborhoods to the desire to ground action and activism in the everyday.

How do we design together from a distance? As a human-centered design studio, this was our big question as the coronavirus became a global reality and we quickly transitioned our operations from a collaborative workspace to our individual homes. Our first response was to simply swap in-person interactions with digital ones. But as we continue to grow into our life apart, we realized that as designers we have an opportunity to work with physical distancing constraints to explore potentially even more inclusive, engaging, and impactful ways of co-designing with people, communities, and cities around the world. As a studio, we’re excited to kick off a series of conversations with our multidisciplinary team on evolving our practice during this time. We begin by chatting with Vinay Kumar Mysore, an Openbox design researcher focused on harnessing the power of design to increase civic engagement and community resilience.

AY: Tell us, what does a design researcher do?

VKM: Design researchers try to make things that are helpful and useful for people by understanding what they need and why. What I do is apply design research to things that are shared across a community — libraries, parks, museums, and city infrastructure — by understanding the different needs and contexts of the people who share them.

AY: Tell us about your most recent design research project for the Martin Luther King Jr. Library in D.C.?

VKM: D.C. Public Library is renovating its central branch, an iconic Mies van der Rohe building, and sought to honor its community and the legacy of Dr. King by building an exhibition space that is a hub for the City’s residents and history. D.C. is undergoing a rapid amount of change and many long-time residents are feeling it. Chocolate City is now the city formerly known as Chocolate City, displacement is acute, and there’s a sense that the story of Washington, the nation’s capital, overshadows their personal story of D.C. The Library and its collections are a special home for residents. Our task as a studio was to use human-centered design to understand what D.C. communities value and need, and to apply these insights to design community-centered exhibits.

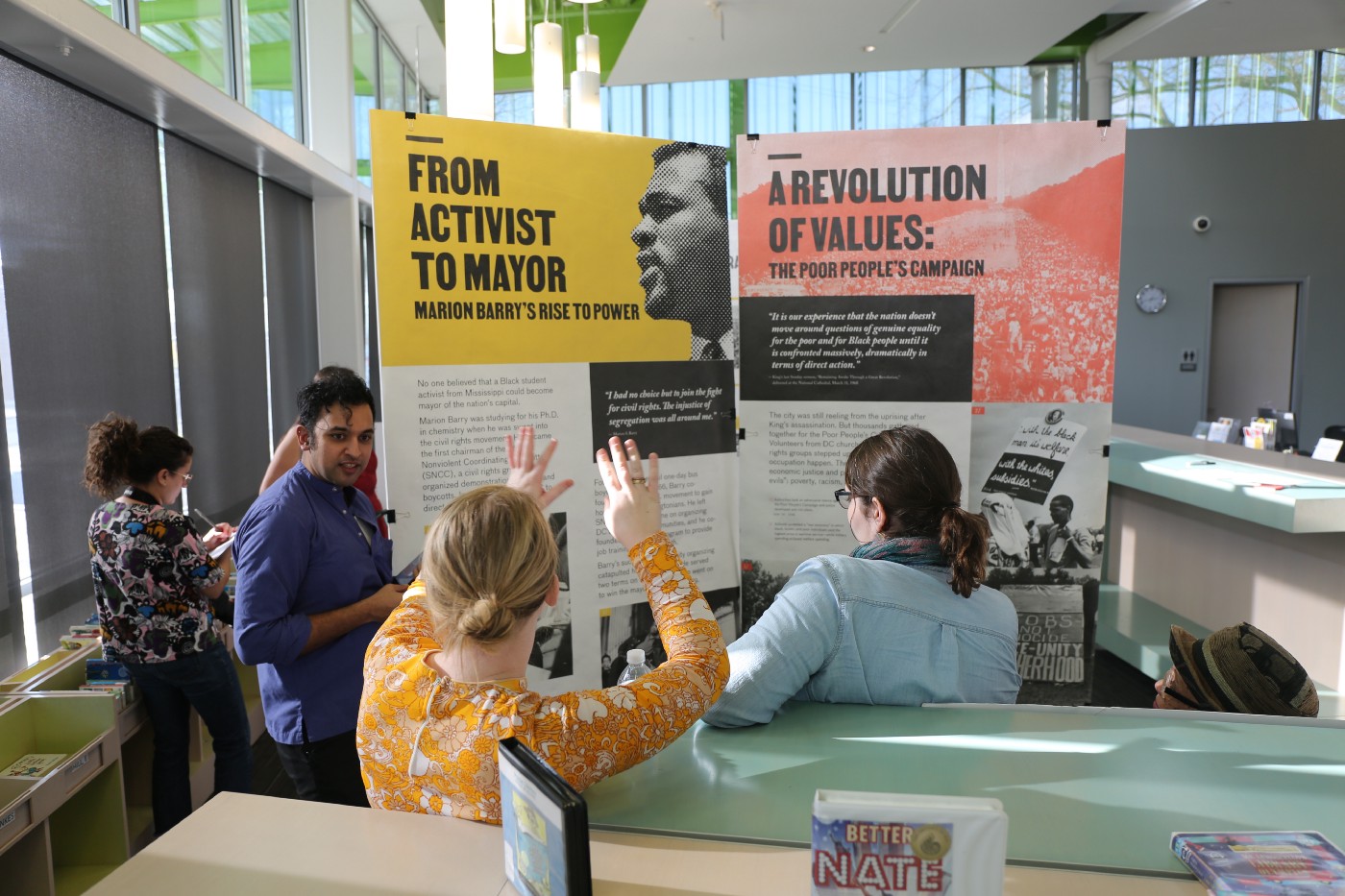

We installed and tested full-scale prototype exhibits within neighborhood library branches, inviting visitors to react to a rich and immersive experience.

AY: How did the project shift when New York City and D.C. began to close?

VKM: We had already done community research in the fall and a first round of immersive prototyping in January. By March, we had planned a final round of feedback to refine concepts for the exhibit. The initial plan was to have physical prototypes inside a library branch. But as we worked on this design phase, the COVID-19 situation was unfolding.

Knowing what we did in mid-March about COVID-19 and out of concern for everyone we’d be interacting with, we decided (within an hour of our train!) to switch to remote work. That evening, the City of D.C. declared a state of emergency and NYC followed on the weekend. In retrospect, it was the right call —but at the time, it felt like a strong reaction.

Openbox met with community members in their homes, offices, and local library branches for generative research. Prompted to bring objects that represent their personal D.C., participants shared mementos and heirlooms, from old irons to cherished pictures, offering insight into their lives and perspectives.

AY: What parts of the project were you able to carry forward and did you let go?

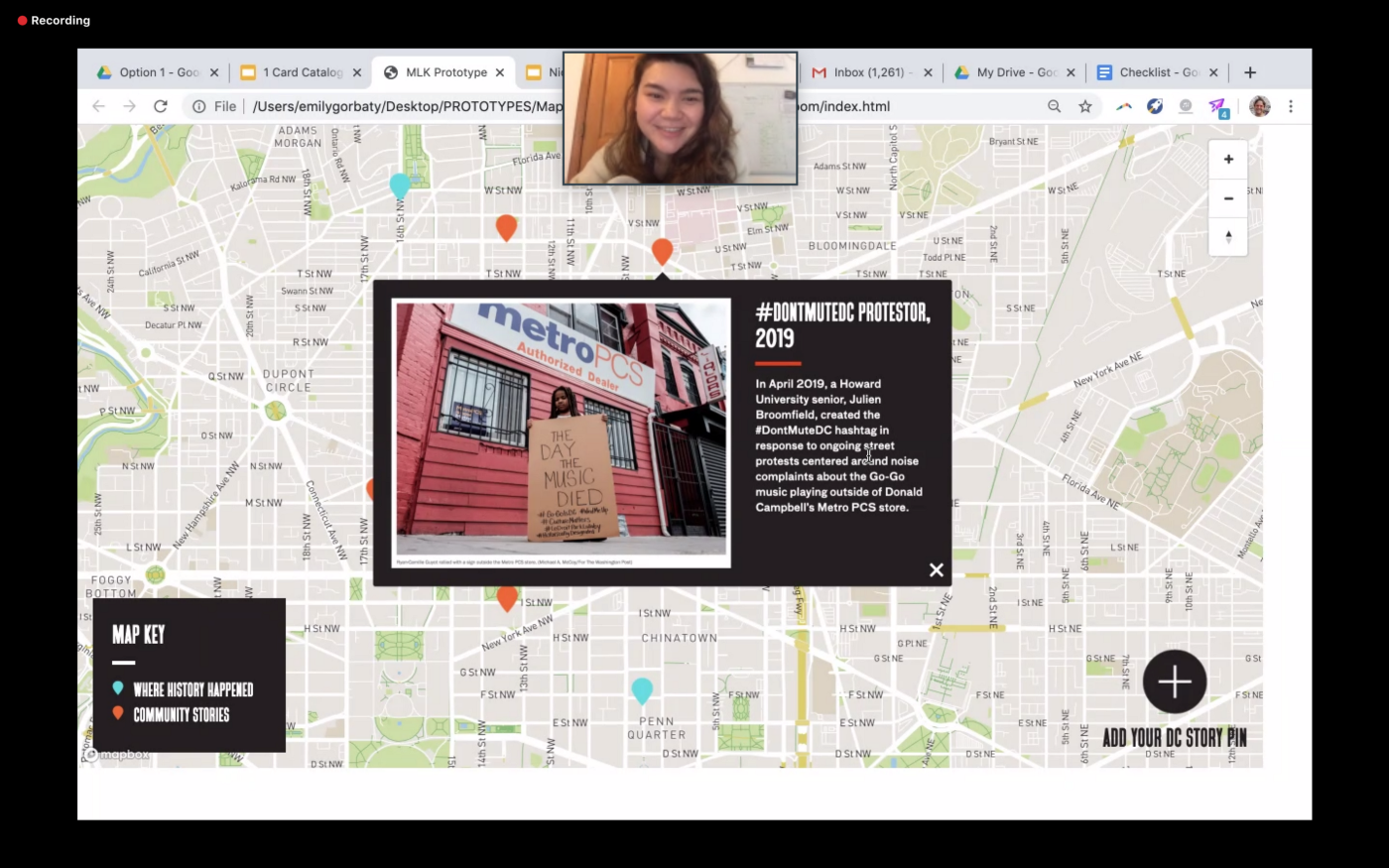

VKM: We really tried our best to carry forward as much as we could. The questions and concepts that needed to be answered remained the same. We had to let go of physical prototypes, but we made pretty immersive digital walk-throughs to simulate the same. We held onto our timeline commitments, but had to change our recruitment strategy. Initially our plan was to engage with library patrons, but we expanded our criteria to connect with community members, organizers, and previous research participants to preserve the integrity of our human-centered approach.

AY: What was the most energizing part of shifting the design research process to a remote one?

VKM: It was a quick pivot to very a different way of research! We were all hands on deck, sprinting to redesign all our prototypes to work as digital interactions, recruiting participants, and redesigning our research methodology— all within 96 hours! It was an exhilarating push. The community response and support was really rewarding. We connected back with community members and organizations we had worked with previously, and they all helped to support what became two days of online concept testing.

Virtual prototypes invited participants to engage with concepts from their own home. Managing the technical and interpersonal demands of remote community research is now an evolving part of our practice.

AY: Tell us about what you learned about the challenges and possibilities of doing community research from afar?

VKM: Certainly there was a technology learning curve and with that, came another vector that mediated inclusion in our process. We work with a lot of communities that experience many forms of systemic exclusion and the digital divide is a real thing. We had participants unable to join sessions because they lacked computers or Internet service, in addition to the many challenges COVID-19 has brought to bear on communities.

However, there is enough of a community of practice and technology that many elements of remote research remained possible. My favorite was discovering the remote control function on Zoom that lets participants test a prototype directly on our own computers. And there is definitely room for different kinds of creative experiences to facilitate design research. From a research perspective, it’s a new challenge to build rapport and understand non-verbal cues on a video chat. We had some past participants participate (try saying that fast three times!) and familiarity helped us better contextualize their feedback.

AY: As many designers and researchers continue to work remotely, what are some of the key insights you’ve gained that you’ll take with you moving forward?

VKM: As a studio, we’re creating new ways of navigating through technological needs as that has now become a raised barrier to inclusion. We’re asking ourselves what are the ways that different inequalities are exacerbated and need to be accounted for in research methods. Some questions we’re exploring are:

- What kind of privacy can we help provide for collaborators and participants when they are at home with others?

- How kinds of participant compensation are most helpful given different degrees of lockdown?

- And overall, what kinds of new physical and digital spaces can we make for research and social connection within shifting public health constraints?

In both tactical and practical terms, we’re approaching our design research techniques anew, including more “old-school” mailed probe kits. We’re also playing with lengths of design phases, new complexities in recruitment, changing needs of our local partners, and substitutes for place-based ethnography. At this point, our main insight is the need to keep asking these difficult questions, while deepening our commitment to equity and inclusion as this global crisis unfold.