Agents were all the rage in 2024 and are a rage as we move into 2025. I have been thinking about this topic for quite some time as well, and wondering what role would a product designer play in helping shape these various agents. A big value prop of agents is that humans can ask agents to execute a task on their behalf. Agent thus acts as an “operator”, a functionality that OpenAI recently launched and the role of human becomes that of a director and reviewer (A concept introduced in this paper published in CHI, 2024). However, as agents become more complex, relying solely on the final outcome can introduce a lot of risks to the system and thus affect its eventual adoption. In this article, I share a few insights and a practical framework to help UX designers think about designing an agent. Each step in the framework gives readers a few questions to ponder upon and shows it in action with a hypothetical example of an AI agent for travel booking (thanks to ChatGPT for the hypothetical example!)

What is an agent?

Before, we get into the details of the framework, let’s level set by defining an agent. In simple terms, an agent is an autonomous system that perceives its environment (in this case, whatever input is provided by the user), makes decisions (based on the knowledge it has), and takes actions to achieve the user’s goal. Agents can proactively initiate actions based on user-defined objectives, and adapt to dynamic inputs and environments (provided by the user or as explored by the agent along the way to achieve a specific objective), which is different than traditional software.

For product designers, this means shifting from interface-driven design to systems thinking, where the focus is not just what the user sees but how the system operates behind the scenes.

How can designers contribute to the agent design?

So far, designers have focused on user interfaces and workflows, ensuring that humans can effectively interact with the software. However, designing an agent requires a deeper understanding of the system’s behavior, decision-making, and human-AI collaboration. One way to do this is with what I define as “agent-centered design”.

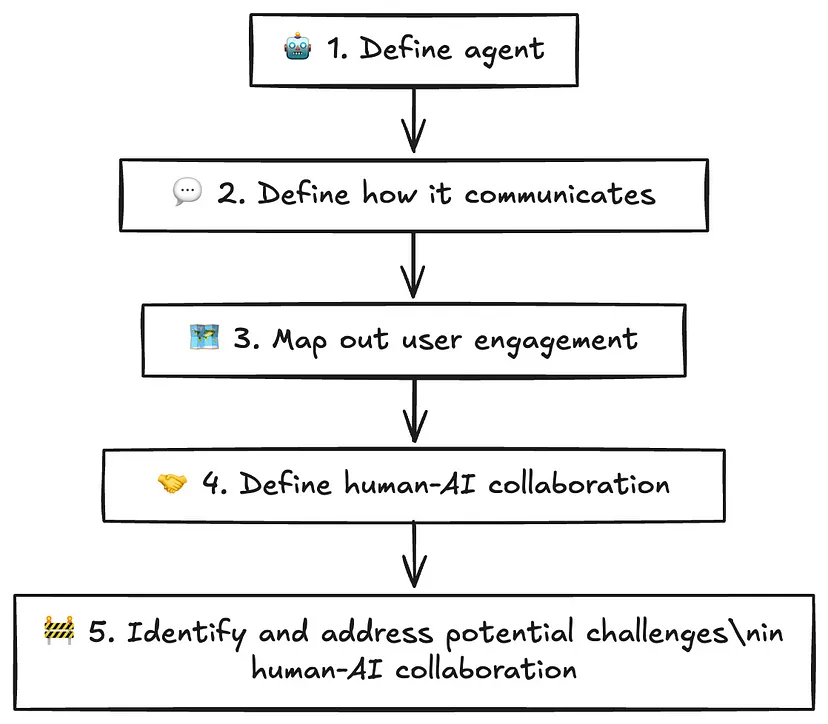

Agent-centered design: a 5-step practical framework to design an agent

Instead of building AI around existing human workflows, this methodology focuses on designing agents with clear personas, needs, and communication patterns — creating a collaborative partnership between humans and AI.

It takes inspiration from user-centered design and defines a complete agent persona. This persona includes an agent definition, how the agent communicates, how the user engages with the agent, the role of the agent and human for the use case, and describes potential challenges in the human-AI collaboration for a specific use case. In this framework, I try to model the agent persona based on a human persona. Just as each human is different, has unique characteristics, and adapts their persona based on the task, each agent is and will also be different.

1. Define the agent

Just like humans are good at certain things, and have superpowers and blind spots, agents are also good at certain things, have superpowers, have a way of making certain decisions, have blind spots, etc. In the agent definition step, you define the scope of the agent’s work and the task the agent is supposed to execute.

To define the agent, ask yourself:

- What task does the agent do?

- What are its decision-making capabilities and limitations?

- What should the agent do and shouldn’t do?

Seeing this in action: For the AI agent for travel booking, the agent books flights, hotels, and generates an itinerary. The agent cannot book multi-leg itineraries, cannot guarantee real-time seat availability, and cannot handle last-minute changes for hotels and flights. The agent should find the optimal itinerary by looking at travel websites, reviews, etc. The agent shouldn’t act without user approval for tasks requiring payments.

2. Define how it communicates

Not every human communicates in the same way. Some are succinct, some are verbose. Some are introverted, some are extroverted. You get the gist! Human communication is complex. The same applies to agents. In this step, you define how and when the agent communicates with the user.

Specifically:

- How does the agent communicate its state to the user?

- How often does the agent communicate its state to the user?

- When does it communicate the state? Are there situations in which the agent is proactive vs reactive?

- At what granularity does it communicate the state?

Seeing this in action: An idea of how this agent could communicate to the user could be multi-fold. If the user is looking at the interface while the agent is working, the agent could expose its inner workings like showing which travel website it is looking at, which review it is looking at, etc. If the user is not actively engaged with the interface, then the agent could send a notification once the search is complete. The notification could send a summary of what it found instead of showing the information in depth.

3. Map out user engagement

If I ask another human to do some work, depending on how complex the task I gave them, I might want to be still engaged in the process. Similarly, just because I gave them some work to do, it doesn’t mean that I couldn’t still go back to them and ask them to make changes to my request or their task mid-point. Now, imagine if instead of giving this task to another human, I gave it to an agent, why should my expectations change?

Ask yourself:

- Is the agent fully autonomous or semi-autonomous? Are there specific decision points that require human intervention?

- Are there specific points where the user can affect the execution of the agent even when no input is required?

Seeing this in action: A potential way to map out the user engagement for AI travel planners could be something along the following lines — The agent should not take any action that leads to payments. So every time the agent comes across such a decision point, it should send a notification to the user to get explicit permission. Additionally, if the agent doesn’t have enough information about user preference (maybe the user provided a very vague preference) then the agent should pause and ask the user to clarify their preferences. Since the agent is expected to take around 2–3 minutes to generate the desired output, the user cannot affect the execution of the agent once it starts booking the itinerary.

4. Define human-AI collaboration

Continuing on the same analogy of a human (person 1) asking another human (person 2) for help. Depending on the complexity of the task, Person 1 might define a contract with Person 2 on how they would like to take their collaboration forward. Would there be certain checkpoints when they would meet? If any help is needed, how would person 2 handle this situation? The same applies to designing a human-AI collaboration.

Ask yourself:

- What are the actions that the agent can take autonomously?

- What are the actions that need human input?

- How does the system handle situations when the AI is uncertain?

Seeing this in action: An example of actions that the agent could take autonomously could be searching for booking, visa, baggage policy alerts, price drops, and suggesting better details. Examples of actions that need human input could be confirming booking and payments, resolving conflicting preferences like budget vs convenience, and handling unexpected changes or edge cases like multi-city itineraries and special airline requests. When the system is uncertain, the agent will ask users for clarification with an option for the user to take over. The situations where the user must take over could be to handle refunds and disputes, subjective trade-offs beyond what was specified in the preferences, any last-minute changes, etc.

5. Identify and address potential challenges in human-AI collaboration

Finally, when humans collaborate together, they put measures in place to keep accountability, set the right expectations of the deliverables, and potentially create a mechanism to get person 1’s help. The sooner these processes are established, the likelier it is for persons 1 and 2 to have a successful collaboration. When person 2 is now an agent, think about:

- How do I help users establish trust in the system even when they are disengaged with the whole process?

- How do I make it clear to the users what the agent can and cannot do to tackle any expectations mismatch?

- How do I reduce the context-switching burden from agent-driven work to manual work?

Seeing this in action: Since the agent takes 2–3 minutes to generate the output, it is likely that the user may not be as disengaged with the process or that context switching will be a burden. However, showing the agent’s decision-making criteria at every point in time might help users establish trust in the system, especially when it comes to getting the best deal possible. It could also show past successful outcomes of the user and other people who have used this agent, further establishing trust in the system. The agent can further provide examples of good and bad specifications of user preferences, for example, itineraries that the agent can generate, etc.

Conclusion

In summary, As AI agents become an integral part of digital ecosystems, UX designers should look beyond interface design and think about agent behavior modeling, decision transparency, and human-AI collaboration strategies. The future of UX isn’t just about designing screens — it’s about designing intelligent systems that work together with humans. To be future-ready, Agent-centered design provides a practical framework for designing an agent that is usable, trustworthy, and seamlessly integrated into human workflows.

The article originally appeared on Medium.

Featured image courtesy: and machines.