Chapter 2: How Story Works

For, the more we look at the story (the story that is a story, mind), the more we disentangle it from the finer growths that it supports, the less shall we find to admire. It runs like a backbone—or may I say a tape-worm, for its beginning and end are arbitrary. — E. M. Forster, “Aspects of the Novel”

Humans are sense-making creatures, and story is our most critical sense-making tool. As humans, we’ve evolved and innovated story over millennia as a way to understand our world. For example, there is evidence that ancient cave dwellers learned how to trap an animal and not go hunting alone through the use of stories.

Given how long we’ve lived with story, it’s not surprising that Aristotle uncovered a working model for it long ago. Basically, he said that every story needs three things: characters, goals, and conflict. What weaves these elements together is a structure or a series of actions and events that have a shape to them.

Fortunately, story and its underlying structure is straightforward, simple, and can be easily learned. That’s why it’s so powerful — for books, films, and products.

Story Has a Structure

First, every story has a beginning, middle, and end — with the middle typically taking up a longer period of time than the beginning or end, as shown in Figure 2.1

Figure 2.1 The parts of a story.

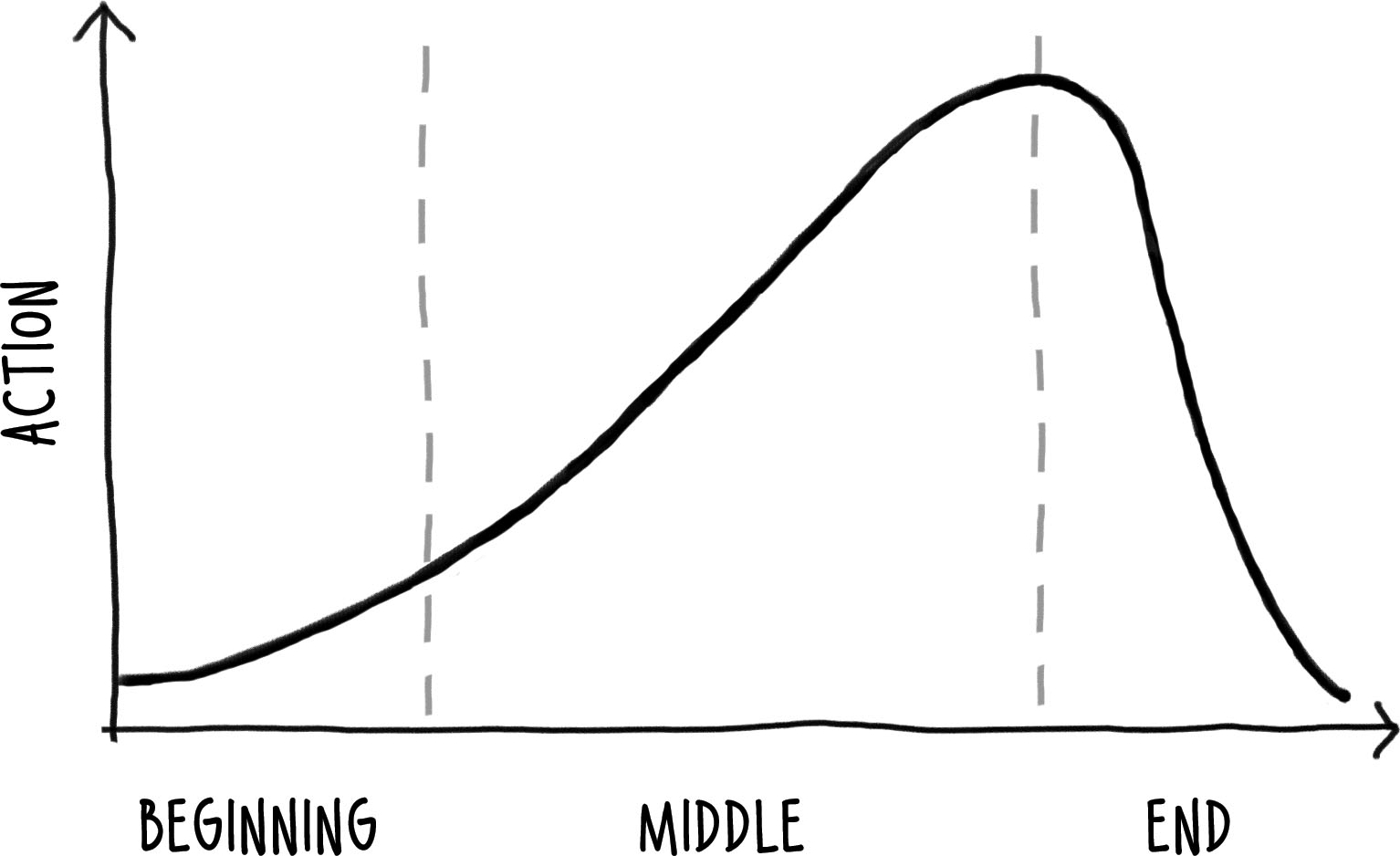

Next, every story has a structure, similar to what you see in Figure 2.2. It’s typically called the narrative arc or story arc, which is a chronological series of events.

Figure 2.2 A story arc.

While the X-axis in Figure 2.2 represents time, the Y-axis represents the action. In other words, you can visually see in the figure that the story builds in excitement, the pace of its action increases over time until it hits a high point, and the story winds down before it ends. When the story doesn’t wind down and instead ends while the action is still rising or at a peak, the story is called a cliffhanger.

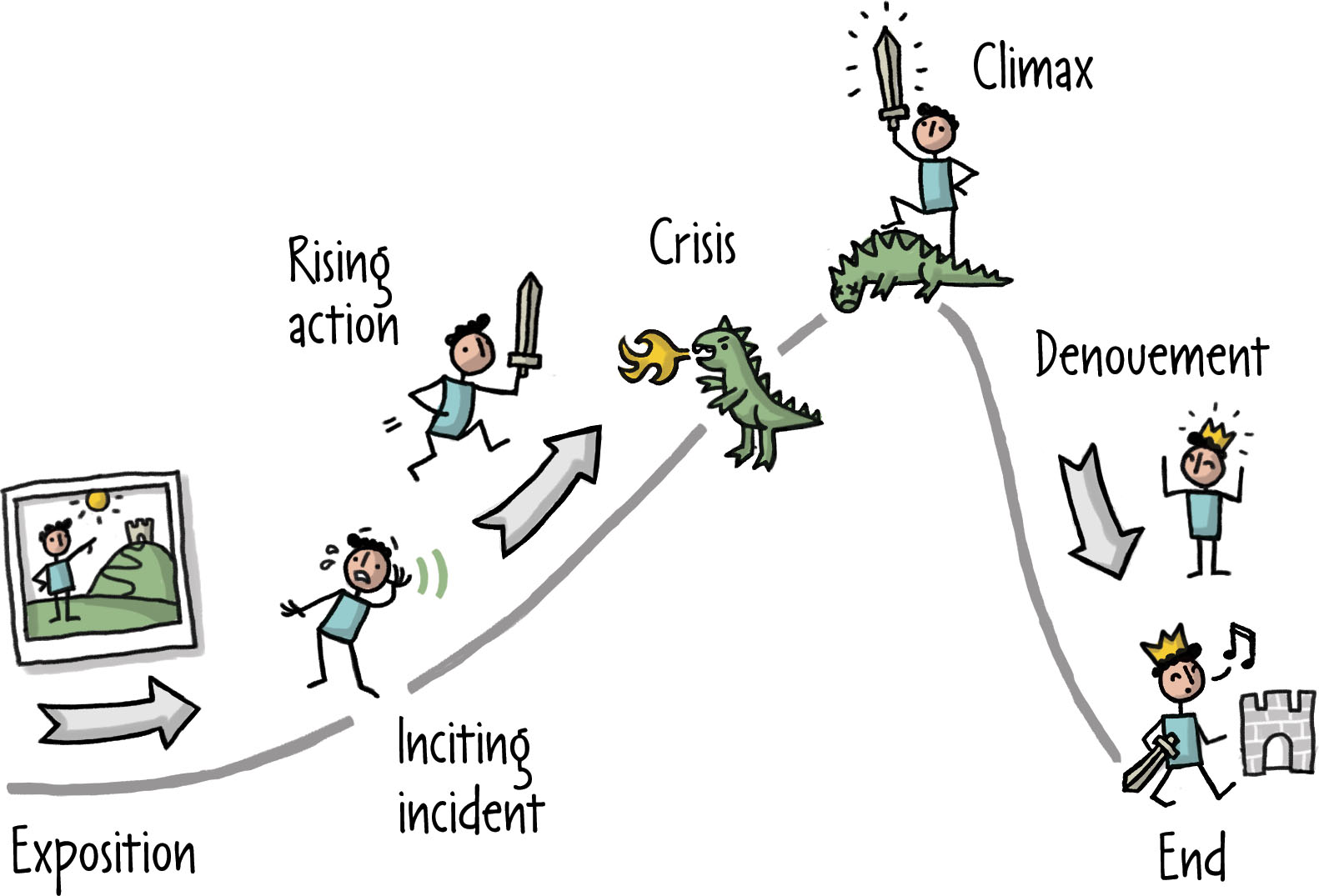

Every narrative arc has specific key plot points and sequences, as shown in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3 Plot points on a story arc.

Let’s dissect the narrative arc of a story. Narrative arcs are comprised of the following elements:

- Exposition

- Inciting incident or problem

- Rising action

- Crisis

- Climax or resolution

- Falling action or denouement

- End

Exposition

During the exposition, you are introduced to the world of the story, the characters, and some kind of big goal. There is a main character, and that character wants something. Big. The exposition functions not only to set the stage of a story, but also to get the person on the other end — you, the viewer — interested and engaged with the main character or characters and what drives them. At its most powerful, a good exposition will compel you to see yourself in and identify with a character or a set of characters. At the very least, it compels you to empathize with them.

Take for example the 1985 feature film, Back to the Future. In the exposition, you meet Marty McFly, who lives in Hill Valley — any suburb USA. His family isn’t very ambitious, but Marty has plans. He’s going to make something of himself. Marty has a friend, Doc — a mad scientist who built a time machine (see Figure 2.4). All very cool.

Figure 2.4

In the exposition to Back to the Future, you are introduced to Marty, Doc, and their time machine. In a movie like Back to the Future, you’re compelled to empathize with Marty. You don’t have to like him. You just have to understand him, his goals, and why he wants to pursue them.

Inciting Incident or Problem

The inciting incident is the moment where something changes or goes dramatically wrong in the world of the story. A problem surfaces and gets in the way of the character meeting his big goal. The moment when the hero is thrust into leaving his safe world in order to fix the problem is called the call to action.

Neuroscientists have shown that when you listen to or watch a story, it’s as if you are experiencing the story in real time. As action rises, your pulse might quicken or your palms get sweaty. Something startles you, and you jump. Stories are not just about looking or listening, they are about being. The inciting incident is the first hook or trigger point in a story that amplifies if and how you identify with the main character, what problems he has, and what he has to go through to fix that problem and meet his goal. It’s what gets you hooked. When the main character is called to action, it’s as if you, the viewer, are called to action. Your brain starts working in overdrive to figure out what will happen next and how the hero will right the wrong.

In Back to the Future, the excitement of a time machine doesn’t last long; militants shoot Doc in a parking lot in an attempt to retrieve plutonium that he stole from them (see Figure 2.5). Not good. In an attempt to escape, Marty ends up driving the time machine to 1955 and then finds out that he can’t get home. That’s a problem — a meaty enough problem to name the movie after. Marty’s call to action is simple: to get back to the future.

Figure 2.5

Inciting incident: this is the point in Back to the Future where the story kickstarts into action.

Rising Action

After the problem surfaces in the inciting incident, the protagonist of the story goes on a journey to right that wrong. We spend the rest of the story not just seeing how it all pans out, but also feeling how it pans out. A good story escalates during the rising action, creating new tensions and conflicts that help move the story forward. As the story builds, the audience’s anticipation and excitement builds simultaneously.

During the rising action of any good story, there is also plenty of conflict to keep the audience engaged. Without conflict, endings come too easily, and the audience is unconvinced or bored or both. In this sense, humans are easy — because to keep them engaged, you save the best for last.

In Back to the Future, Marty sets out to find 1955 Doc. They try to get Marty home. But they can’t solve the problem, or the movie would end. So things get weird. Marty meets the younger version of his mom. His mom has a crush on him (see Figure 2.6). Marty meets his dad’s nemesis, Biff. Biff becomes Marty’s nemesis. Things get tense. And more tense. And as a result, more engaging. We become more and more invested in how Marty will get back to the future, scene by scene.

Figure 2.6

In this scene, Marty starts to realize that his mom is taking an interest in him and his Calvin Kleins.

Crisis

The story culminates at the point (or series of points) of maximum conflict — the crisis. It’s the point of no return. Nothing the hero has done has worked, and he is further from the goal than ever. The story either has to right itself or end in tragedy. If the story ends with neither, then it’s a cliffhanger and is incomplete. At this point, the main character has gotten so far and is so close to meeting his goal that it’s impossible to just give up. Defeat or success is the only option.

In Back to the Future, the crisis starts when Marty is close to figuring out how to get back to the future. But because his mom falls in love with him instead of falling for his father, there is the chance that he will never be born in the future. Because he might never be born, Marty begins to disappear (see Figure 2.7). The only way to get over this hurdle is to make sure that his parents end up together. But how? And then what? Once he overcomes this obstacle, he still has to figure out how to get home. How will this all play out, you wonder, as you are now totally invested in the outcome of the story.

Figure 2.7

Marty starts to disappear while he’s on stage at a school dance. Will he or won’t he get his parents together so that he can live? Suspense!

Climax or Resolution

Just as it sounds, the climax occurs at the top of the story arc. It’s the most important part of the story. It’s the high point. The final showdown. This is the point at which the hero’s fate and the direction of the story are determined. As such, it is also the most exciting part of the story. It’s the point at which all of that tension and will he or won’t he from earlier scenes culminates in you jumping out of your seat, cheering, laughing, feeling satisfied that you solved the mystery before the main character, or simply smiling because well… that was awesome.

Climax is why you are glad that you tuned in and stayed tuned in.

Sometimes, this point is also called the resolution, which occurs when the main problem from the inciting incident and the hurdle from the crisis are resolved. Problems and hurdles are either resolved or they’re not, and you’re left with that tragedy or cliffhanger.

In Back to the Future, the climax begins when Marty’s parents kiss at the high school dance. At the very least, this means that he can finish playing his song on the guitar. Excellent.

But wait! There’s more!

There’s a clock tower and lightning (see Figure 2.8). The underlying problem still needs to be solved: Marty needs to figure out how to get home. In a bolt of lightning, boom, Marty gets catapulted back to the future. Even more excellent.

Figure 2.8

Climax and resolution in Back to the Future. Doc figures out how to get Marty home by harnessing lightning to power the time machine from atop a clock tower.

Think of the climax as a sort of pay-off. This is why you sat through one hour and 30 minutes. It’s exciting. It’s suspenseful. It’s satisfying. The climax is not only the best part of the story, but it’s what you remember most. It’s why you come back. It’s like a reward, or a thank you for tuning in and staying tuned in.

But then what? Imagine if Doc managed to harness the power of lighting, get Marty home, and the movie just ended. Stories can’t just end on a high point, or they’re as unsatisfying as a cliffhanger. Once Marty gets back to the future, he still needs to actually get home. For that, you have the falling action or denouement.

Falling Action or Denouement

Have you ever listened in frustration to someone having a conversation on her mobile phone? If you had to listen to the entire conversation in person, with both participants audible, it wouldn’t be nearly as frustrating. You could probably tune the conversation out or listen and just not care. It turns out that the main reason why these conversations are so frustrating is that your brain naturally wants to complete the conversation. Just hearing half triggers an automatic, unsatisfying response that leads to frustration. Researchers call this phenomenon a halfalogue: half of a conversation that your brain naturally and uncontrollably tries to complete.

Humans, it turns out, need closure. Stories, likewise, need closure so that humans can feel closure.

Imagine if The Wizard of Oz ended after Dorothy had defeated the wicked witch. Goal met. The end. You’d be frustrated. Your brain would jump into overdrive as you wondered what then?< What about Kansas? Your mind would jump full circle as you started to remember the exposition of the story and wanted to know not just how evil was defeated, but how the story ended. What happened to Dorothy after she defeated the witch? For this reason, stories need not just to resolve their conflict and show characters meeting their goals, but also to have a fancy ending called a denouement, a word derived from the French meaning “to unknot.” This is the part of the story when the conflict is resolved and the action starts slowing down in pace and excitement toward the closing scene. It’s how everything in the story gets wrapped up.

The line between the climax/resolution, falling action, and ending can be blurry and happen so quickly that it’s hard to discern the difference between one and another. What matters is that the climax is exciting, and it resolves the major conflict or problem—the falling action leads to closure. In Back to the Future, Marty McFly goes home (see Figure 2.9). This is the falling action for many adventure tales: the hero goes home.

Tension releases. Ah… all is good in the world.

And… it’s important that home is better than when the story started and where the character left it. In this case, it’s much better. Marty’s parents are successful. Biff is his family’s servant. Marty got the truck he always wanted. Not bad.

Ideally, the falling action or denouement should happen as quickly as possible. As much as humans need closure, they’re also impatient beings. Once the action has died down, there is only so much that can keep your attention. Just because you want closure, doesn’t mean it needs to be dragged out with a 10-minute long ticker-tape parade. (I’m looking at you, George Lucas.)

Figure 2.9

After his adventure through time, Marty lands back home in his present-day Hill Valley.

End

Quite literally, the end is the end. Characters grow throughout a story and should be changed by the end. Remember that big goal established in the exposition? How did it all work out? At this point, the character should meet her goal and hopefully learn something along the way. Along the same lines, just like your cave-dwelling ancestors, you should be changed and have had a new experience, or have learned something by the end of a good story.

In Back to the Future, the story ends with Marty’s girlfriend asking him if everything is OK. “Everything,” Marty says, “is perfect.” They embrace (see Figure 2.10). Now, if this were a classic Hollywood film, the two would kiss, the screen would fade to black, and the credits would roll. The end.

But as you may remember, this is the first installment of what would become a trilogy. Before you get too comfortable in your plush movie seat or sofa, you see a flash and Doc running up the driveway. Something’s not right. There’s a problem and Doc needs help. Where does he want to take them? To the future! And so a new story is kickstarted… a sequel. Just because a story has come to an end and has closure doesn’t mean it can’t lead to another story… and another. We call those serial stories. Serials keep us engaged episode by episode. Serials are fun.

Figure 2.10

All is well.

Building Products with Story

…in real life we each of us regard ourselves as the main character, the protagonist, the big cheese; the camera is on us, baby. — Stephen King, “On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft”

Let’s face it: you probably don’t make multi-million dollar epic movies like Star Wars; instead, you make websites, software, digital or non-digital services—all things that people don’t just consume, but actually use. Just as with a movie, story flows through how people find, think about, use, and recommend your products.

Consider this photo for a moment (see Figure 2.11). It tells a story of an Apple product that comes installed on every iPhone. You can probably guess what product it is.

Figure 2.11

Assuming you guessed FaceTime, you are correct. If you guessed “Tinder for seniors,” that’s not an Apple product. But, as some of my past workshop attendees have demonstrated, a product like that also has a compelling story to it: a story that you can easily use to prototype to test out a design hypothesis. What we see in this still photograph is an entire story encapsulated in one simple frame. Rather than spell it out for you, I want you to take a moment to consider this narrative within the framework I’ve laid out so far.

What do you see?

How do you know that these people are using FaceTime?

Well, they’re older, so maybe they’re grandparents. They’re smiling. What makes grandparents smile? Grandchildren? And? Maybe their grandchildren are far away, and they want to see them. Why can’t they see them? It’s too expensive to fly and not realistic to do that on a regular basis. Why not call them up? They already have an iPhone or an iPad and use it to play the crossword puzzles all day. And so forth… they are calling them up. Just with video. Using FaceTime is as easy as using the phone. It is a phone. But with video. You just look at it instead of holding it up to your ear… like magic.

This is the type of computational math that your brain makes during a series of micro-seconds when you look at a photograph like this and try to understand what you see. Your brain seeks out a story in the data it consumes. And that story has a structure to it, whether you realize it or not. This behavior is so natural that you probably don’t even notice that you do it.

Story is not only a tool your brain uses to understand what you see, it’s a tool your brain uses to understand what you experience. In other words, the same brain function that you use to understand what you see in a photograph is the same brain function you would use if you were one of those grandparents using FaceTime. Life is a story. And in that story, you are the hero.

In Badass: Making Users Awesome, Kathy Sierra argues that creating successful products is not about what features you build — it’s about how badass you make your user on the other end feel. It’s not about what your product can do, but instead about what your users can do if they use your product.

Amazon, for example, is not a marketplace with lots of stuff. It’s a way for you to have a world of goods at your fingertips. Using this perspective, you can see how your job building products comes down to creating heroes. When I rush-order toothpaste with one-click on Amazon to replace the toothpaste I used up this morning? As boring as it sounds, I’m a hero in my household. This job you have of creating heroes isn’t just an act of goodwill. In the time I’ve spent over the past two decades helping businesses build products that people love, I’ve seen what happens when people feel good about what they can do with your product. They love your product. And your brand. They recommend it to others. They continue to use it over time…as long as you keep making them feel awesome. They even forgive mistakes and quirks when your product doesn’t work as expected, or your brand doesn’t behave as they’d like. People don’t care about your product or brand. They care about themselves. That’s something that you can and should embrace when you build products.

What’s great about story and its underlying structure is that it provides you with a framework—a formula, if you will—for turning your customers into heroes. Plot points, high points, and all. Story is one of the oldest and most powerful tools you have to create heroes. And as I’ve seen and will show you in this book, what works for books and movies will work for your customers, too.

If you want to read the whole book, you may find it at Rosenfeld