Save

If you are UX designer and have not yet taken a Saturday to binge watch Netflix’s latest series, Stranger Things, it is highly advisable that you do so. Not only is the show fun, science-fiction-based, and ostensibly geeky, but it also brings awareness to what has truly been an incredible few decades of technology. Set in the 1980s, the characters of Stranger Things utilize massive walkie-talkie devices, refer to the development of the new AV club at school, and perhaps most importantly (spoiler alert), play around with the idea of a mimetic, virtual universe that parallels our own. With the re-popularization of virtual reality technology in recent years, it is difficult not to wonder if the writers of Stranger Things intentional wove such a topical narrative into the series plot. Nevertheless, what is brought to the viewer’s attention is the very stark contrast between what was understood of virtual reality back then, and what is understood of virtual reality now. Formerly more akin to a scene from The NeverEnding Story, virtual reality has grown to be more real than ever. For interaction designers, this poses a very interesting challenge to the design process. How does one invent a completely new world? As always, the answers to our contemporary conundrums can be found by looking to the past.

The current hype around virtual reality technology belies its age. VR has been around for quite some time. According to the virtual reality society, one of the very first devices to influence this area of research was created as early as the 1950s. Known as the “Sensorama,” cinematographer Martin Heilig constructed a machine that placed an individual inside a movie-theater like box, wherein a video was projected along with smells and movements.

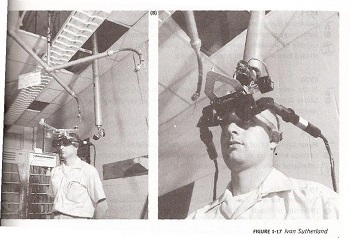

In the 1960s, MIT graduate Ivan Sutherland expanded upon this idea with his invention “The Sword of Damocles“. A head-mounted display (HMD) system, “The Sword of Damocles” enabled users to actually instruct their experience with their body rather than a controller. In 1991, Sega developed the Sega VR headset, which furthered many of the advancements of “The Sword of Damocles.” The Sega VR was a HMD device that effectively tracked and responded to the movements of the participant while allowing him or her to move throughout a virtual world. The Sega VR, along with various other devices of the 1990s, set the stage of our current models of virtual reality technology. Devices such as the HTC Vive, which permits a wide range of movement within a virtual world, could not be possible without its predecessors. virtual reality devices have moved away from relying on external cues such as smell to relying fully on our internal states and our ability to suspend disbelief.

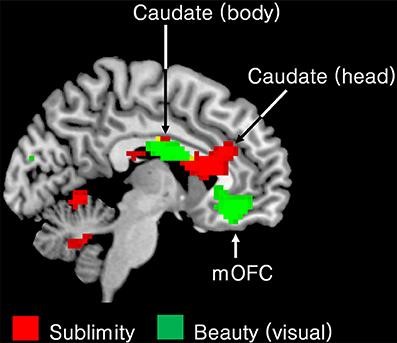

How helpful would it be, then, if we could better understand exactly how to tap into this part of the human brain responsible for suspending disbelief? Based on the research of neurologist Semir Zeki, we may know a lot more about this state than we think. Semir Zeki is a neurologist who performs research on the neurology of aesthetics. A study conducted in 2014 showed that for participants viewing “beautiful” art objects versus “sublime” art objects, those who viewed something of the Sublime demonstrated very different results with fMRI imaging than those who looked at something beautiful. What is the Sublime exactly? The Sublime is a term that was popularized during the Romantic period of the 1800s. It was used as a way of describing the feeling of awe or terror we feel in the face of something overwhelming. If you can imagine peering down a cliff, or looking up at the stars in a clear night sky, then you can imagine experiencing a Sublime feeling. Thus, in considering virtual reality, it is easy to see how stepping into a VR world parallels viewing something Sublime. Thankfully, this tie gives us our first clue as to what unlocks a successful virtual reality experience.

Beautiful

Sublime

So, how did the human brain look under Zeki’s inspection? His study demonstrated that a participant, when viewing something beautiful, showed low levels of activity in the brain’s hippocampus. Yet a participant, when viewing something of the Sublime, showed the brain’s hippocampus to be on fire. The hippocampal region is the area of the brain responsible for a sense of place in a given environment. It is what enables you to understand where you are in conjunction to other objects in a room. When viewing something Sublime, like a thunderstorm, we lose sense of ourselves as this area of the brain goes haywire. In a virtual reality environment, this loss of self is the key to a meaningful experience. Our hippocampal region must ignite, forcing us to lose a sense of true reality.

In a study conducted in 2014 at UCLA, neurologists found further evidence to support this theory. The study, published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, shows that the brain, when participating in a virtual reality environment, responds very differently than it does in real environments. Scientists placed rats in a virtual reality environment and then in a real environment in order to monitor if, at all, a difference would occur in their neural activity. They found that the neurons in a rat’s brain fire very differently in a virtual world than they do in a real world. In a virtual world, the neurons in the brain’s hippocampus seemed to fire at random, whereas in the real world, the neural activity of the hippocampus was much more systematic. Cells known as “place cells” exist in this area of the brain, which help us to mark where we are in relation to a given surrounding. A widely accepted hypothesis, published in the 1978 book The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map, posits that the hippocampus forms cognitive maps, or mental representations of the physical space we inhabit. If virtual reality technology can somehow throw off these GPS cells, we are automatically placed in unknown territory.

While it is currently very difficult to perform fMRI imaging on a subject experiencing virtual reality, it is nonetheless useful to know how to create a powerful virtual reality world. The best VR designs play on the hippocampal region and make us lose our sense of place and time. The history of virtual reality technology shows that from the Sensorama, to the HTV Vive, there was an evolution and growth towards human-centered design. The devices that formerly relied on more external cues now rely heavily on how our minds are built and wired. Although user-experience designers have traditionally accounted for cognitive science in how they design mobile and desktop interfaces, the user-experience of virtual reality is different because it does not prioritize function but instead prioritizes displacement. What is important here is not so much whether or not a user can easily find the correct button, but if the user feels they have transcended our planet. For this reason, we are no longer tackling the same areas of the human brain. How we may strike the correct keys to play on the brain’s hippocampus, however, is an answer for another day.

Image from Stranger Things TV show is courtesy of Netflix

Caitlin Burke

Caitlin Burke is an Associate Product Manager at HBO.