My near-acceptance of an offer to head up a user research consultancy a couple of years ago resurrected my consideration of whether “user research” is the best term to use to label the offering. The term is still popular (though the word “experience” sometimes lies in the middle), but the word “user” can convey a much narrower scope of the service than is often accurate. As I described in Is ‘user’ the best word?, that was true when I was Director of User Research at Studio Archetype and Sapient; there, the label did not always communicate that we did more than only research of “users” and “use.”

Similarly, I recently had a conversation with an ethnographer who wanted to better understand “user research,” thinking it was something she didn’t already do. Given that use of ethnographic research methods is a big part of many user research practices, narrow preconceptions about user research apparently exist even within the applied research community.

In short, it is not always clear what label is best to apply to such an offering. It is also not always clear what its ideal scope or focus should be or should become.

Lots of people conduct “usability research,” but its methods and approaches have lagged behind major changes that have occurred in the world of computing. In Is Usability Obsolete?, an article published in the May+June 2009 issue of interactions magazine, Katie Minardo Scott argues:

Current usability work is a relic of the 1990’s: an artifact of an earlier computer ecosystem, out of step with contemporary computing realities. Usability can no longer keep up with computing: the products are too complex, too pervasive, and too easy to build. And in our absence, users and engineers are beginning to take over the design process. These trends demonstrate the growing gap between usability theory and commercial practice—the “new realities” of computing haven’t been truly embraced by the usability community. The trends are, at a minimum, making traditional usability more difficult, if not irrelevant in the new paradigm.

Michael Hawley argues that researchers tend to rely on tried-and-true older methods that are inadequate for understanding consumer behavior in a world increasingly proliferated with social media and other digital channels. Among the techniques Michael recommends using instead is the monitoring of social media for a real-time view of the “customer decision journey.” Of course, social media monitoring is already being done by non-UX researchers. However, as Lauren Serota and Dan Rockwell state in An Introduction to Casual Data, and How It’s Changing Everything (interactions, March+April 2010):

People are swimming in data like never before. Services like Nike +, Daylum, and Mint allow anyone access to endless aggregations of personal information, thereby increasing self-awareness and shifting perception. Companies also utilize these tools to harvest commentary on Twitter, Facebook, and via customer-service interactions, connecting to the minds of some of their customers more than ever. However, having access to this… ‘causal data’ doesn’t mean that companies/brands, or consumers, for that matter, understand it or have the means to translate it into meaningful direction for business strategy, product development, or design.

While there are a number of firms analyzing the surface value of casual data, there is a need to dig deeper to understand context and higher-level implications. The more connected we become, the more connected our data becomes, and the more we need a structured approach for making sense of it.

The label “design research” is used more and more these days. But when Yahoo! abandoned ”user experience research” for “design research“ a few years ago, previous efforts (some of which had been mine when I was at Yahoo!) to involve UX researchers in the early stages of product and service ideation and conception were undercut. As described by Yahoo!’s Klaus Kaasgaard (pictured), a guest speaker at a UX management course I taught during the spring of 2008, the new label made people think that the research was only relevant to the later design phase of Yahoo!’s product development process.

Narrow interpretations of the label “user research” at Studio Archetype and Sapient prompted us to expand the label to “user research and experience strategy.” Narrow interpretations of the label “design research” at Yahoo! led Klaus to change the label back to “user experience research.” But a much more significant change was made at Yahoo! subsequently: a merger of the UX research group and the market research group formed an organization named “Customer Insights.”

When I was in a management role at Yahoo!, we discovered that market researchers were encountering some of the same obstacles as our UX researchers—obstacles to being appropriately involved upstream in the process to have a more strategic impact on the company. So UX research began to partner with market research in an effort to attain that involvement. In his presentation at my UX management course, Klaus, then Yahoo!’s VP of Customer Insights, spoke at length about the similarities and differences between the goals and challenges faced by market researchers and UX researchers, and about how important the merger had been to achieving such a strategic role. (See also Klaus’s Why Designers Sometimes Make Me Cringe.) In an excellent article in UPA’s magazine (Volume 7, Issue 2, 2008), Robin Beers paints a similar portrait of bringing together the market research and user research teams under the umbrella of “Customer Experience Research & Design” at Wells Fargo. (Use of the word “customer” in both cases probably helped as well.)

Is such a coming together of these two disciplines appropriate for every company? No, as implied by eBay’s decision to split them up after they attempted to bring them together. There are multiple factors to consider when determining what is best for a particular company. But it is important to understand that great benefit can be achieved when the two work together.

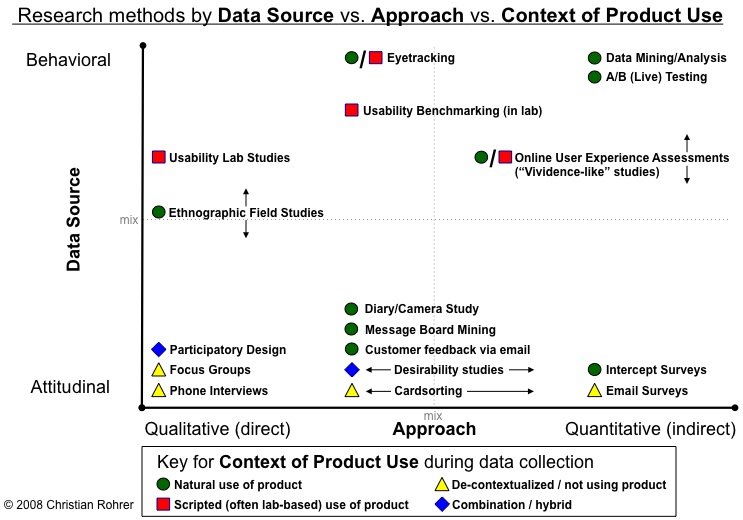

In an October 2008 contribution to Jakob Nielsen’s Alertbox, Christian Rohrer provides a mapping of a wide range of research methods, some typically thought of as “market research” methods, that can help you to better understand their similarities and differences.

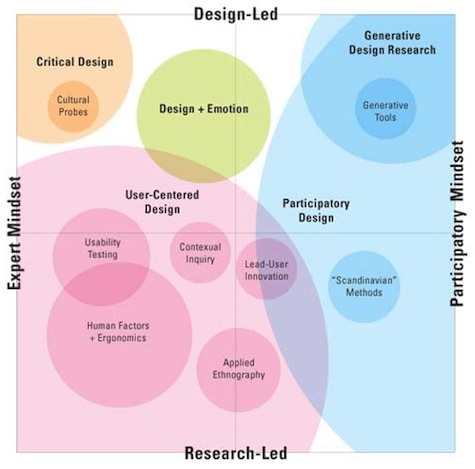

In the November+December 2008 issue of interactions magazine, Liz Sanders provides different insight via her map of “design research.” Here is how Liz describes the map’s organization:

The design research map is defined and described by two intersecting dimensions. One is defined by approach and the other is defined by mind-set. Approaches to design research have come from a research-led perspective (shown at the bottom of the map) and from a design-led perspective (shown at the top of the map). The research-led perspective has the longest history and has been driven by applied psychologists, anthropologists, sociologists and engineers. The design-led perspective, on the other hand, has come into view more recently.

There are two opposing mindsets evident in the practice of design research today. The left side of the map describes a culture characterized by an expert mind-set. Design researchers here are involved with designing FOR people. These design researchers consider themselves to be the experts and they see and refer to people as “subjects”, users”, “consumers”, etc. The right side of the map describes a culture characterized by a participatory mind-set. Design researchers on this side design WITH people. They see the people as the true experts in domains of experience such as living, learning, working, etc. Design researchers who have a participatory mind-set value people as co-creators in the design process. It is difficult for many people to move from the left to the right side of the map (or vice versa) as this shift entails a significant cultural change.

Not only have the design-led perspective and the participatory mind-set been gaining traction, so too has the “gamification” of seemingly everything. Luke Hohmann’s advocacy of the use of methods employing collaborative play is one example of this in the world of research (see What is Holding User Experience Back Where You Work? here in UX Magazine for a sense of what one of Luke’s “innovation games” is about). MindCanvas’s “game-like elicitation” remote research methods are another.

So, what kinds of “user research” should you be offering (or soliciting) these days? What label should be used to reference them? How and with whom should such research be approached? As the world changes, so too is and must at least some of what constitutes this critical offering.