Save

We all get excited about design, especially when talking about the latest innovations from Apple, Google and other amazing leaders of UX. But we often forget that these cool designs and millions of raving fans were only possible because these designs were based on the solid foundations of User Research. Years of not-so-glamorous grunt work went into achieving the intimate understanding of these companies’ customer avatars.

And many times, this has been done “the hard way.”

Every product manager’s dream

Every good product manager (and every good enterprise business analyst) worth their salt is obsessed with knowing everything about their market. They “go to bed” with their customers. They want to know what they eat and drink, what car they drive, what words they use when they’re speaking and what brand of clothes they wear to a party.

Good product managers love to have their marketing “speak” like these guys do, preferably, using the same language, so their clients would literally feel that it’s not the site, it’s the voice inside their head is nudging them to buy.

Yes, this is why we develop personas and that is what drives our task analysis, but where is out data coming from?

Design sessions and interviews…and some observation. But more often than not, that too can only get us so far.

Why observation doesn’t always work

Great products like the iPod and iPhone were not created by observation. And neither was the first car. Henry Ford did not come up with it by watching people riding horses.

Users can be amazingly accurate talking about the things they don’t want

He did not get his ideas from asking people either. They wanted faster horses, not a gasoline engine. Most people had no idea what that smelly noisy thing on his “horseless carriage” actually was. So any survey he might have done on what people wanted would’ve given him no insight.

The biggest problem with observation is that it only gets you that far. You start with an assumption that you can watch the user performing all of their tasks. But they may not be doing them right now.

Let’s take a look at another example.

A lot of things we’re doing today were unheard of just a decade ago. Browsing web on your phone, social GPS… even the texting didn’t come about before people were given the full keyboard on their phones. Observing people using numeric keypads on their Nokia phones 20 years back would not have told us that they would really like to send text messages. The only thing people did with these keypads, except for dialing, was playing games.

Maybe, just maybe, if you had an army of researches, you could’ve potentially seen one out a thousand people do that ugly T9 way of entering letters. But would that ring the bell in your head and urge you to give them a full keyboard, so they could text?

Yes, the observation can really be very useful. And yes, almost always it does provide actionable insights. Yes, we need to develop personas to better understand our users, but we’re seriously lacking on ways of obtaining accurate market insight.

We do have surveys. They could be quick, efficient and inexpensive, but traditional surveys will not give us the results we want and the insight we’re looking for.

Here’s why.

What’s wrong with surveys

Most traditional surveys are set up in a way that they can only prove our guesses right or wrong. And when we are wrong, they don’t offer us a lot of help to figure out what’s wrong. We’re still left with our guesses and assumptions.

Yes, Likert scales offer a bit more insight and yes, they take care of the agreement bias situation where people are trying to tell us what they think we want to hear, but it doesn’t change the main thing that’s wrong with all this – traditional surveys are built around our assumptions.

So why not keep it all open and just let them tell us what they think?

User researchers have been hesitating to use open-ended questions since the beginning of time. Some people liked to keep their data models clean and scientific, and some just didn’t know what to do with all that input. At best, we include the “Other” type-in option in our choice lists, but that’s as far as we used to go. And that is why we were missing all the important insights…

So, now what?

Let’s go back and recall one of the main foundations of user research. Why do we go through all these trouble of conducting surveys, observing users perform their tasks, asking them about the problems they’re having?

Why can’t we just ask them to tell us what they want? Why?

Well, because every user researcher knows, that…

Users don’t really know what they want!

Users didn’t ask Steve Jobs to put a mini hard drive into a small package and give them a thousand songs to take with them. They loved it when they saw it, but they didn’t ask for it. Similarly, nobody asked for an iPhone either. Users did not come up with these ideas and these designs. Apple did.

But users are really good at other things—in fact, users can be amazingly accurate talking about the things they don’t want. They can tell you a lot about the problems they’re having. They can describe how it feels to go through the issues they’re facing and what other problems these issues are causing them.

So how’s that for a source of insight?

Well, good researchers and BAs have been asking questions this way for years now. These questions surrounding what customers don’t want are the key questions asked at most stakeholder interviews. Even salespeople ask these questions. “Tell me about the problems you’re experiencing with XYZ product.” And that provides valuable insight.

But now we hit the brick wall again as we just can’t interview that many people!

Scaling up the interviews

Yes, interviews provide the valuable insight we need, but we cannot interview enough people to find all (or most) of problems that our market or our business users are facing.

The scope creep, the curse of today’s IT projects, is coming from users realizing these things late in our projects. Largely, because we have not asked enough questions BEFORE the project was started in the first place! (We’re also lacking the tools for prioritizing the problems we discover and mapping them to market demographics).

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could tell (and have the numbers to prove) that university students are more eager to buy our iPod than the ‘high tech’ commuters with more money at hand, and that our intranet site sucks because the corporate CMS makes it difficult to publish content and not because the employees are not engaged or the search function is not efficient enough.

So how do we go about doing user research efficiently and effectively?

I’ll show you how.

Introducing two-minute interviews

Here’s how a single researcher can conduct a thousand interviews a week… with accurate results. Well, not the actual interviews. I’m going to show you how to use open ended questions in your surveys effectively, so you get the best of both worlds – the speed, low cost and flexibility of surveys and the richness of information that only interviews could be used to collect until now.

Here’s a typical scenario: We have a consulting practice where we help clients with UX work, and we also offer our own products in the Enterprise Content Management space. To learn about our market, we needed a new approach as we could not interview enough of our potential clients. We could ask them to fill in a survey but, as I said, that would not have been very insightful.

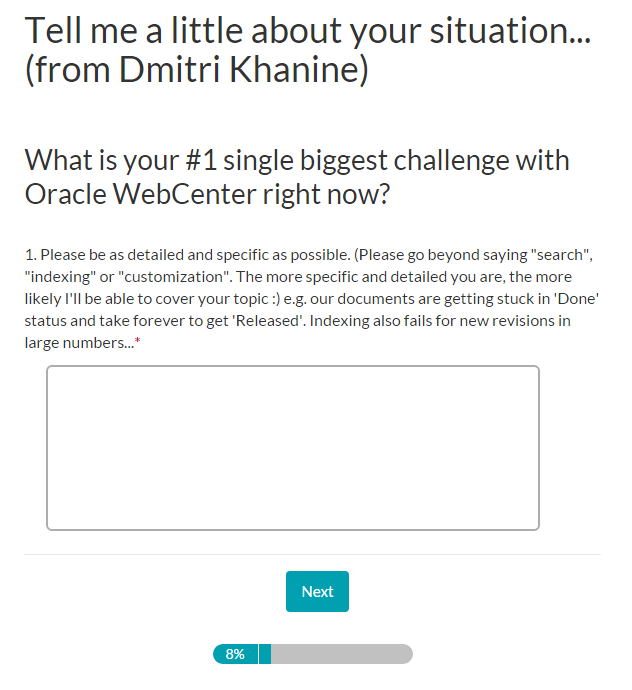

So here’s how you could use an open ended question – ask them about their single biggest challenge with a product or a specific situation that you’d like to improve:

- The first page of survey below asking users about the Single Biggest Issue they’re having with Oracle Content Management. This makes it easy for them to focus on a problem:

Be sure to make your open ended question the first question in your survey. If users decide to only answer one question and leave, this is by far the most important question that you want them to answer.

Once they tell us about their current situation, the only other thing we want to know is – what type of role are they playing with our product or in our situation? In our example, we were asking them if they a system administrator, business user or consultant. This ‘demographic’ information will help us map common types of problems that people will be reporting to us to different types of users.

- Here’s the second page of our survey where we’re asking them our ‘demographics’ questions:

Finally, you may choose to get on the phone with some of your survey takers to further clarify the situation, get a feel of their emotions and so on. When doing so, you should be focusing on the people who demonstrated the highest commitment to fixing the situation – by willingly providing you the most detailed answer and also giving you permission to call them.

And that’s it. So we’re now done collecting information and it’s time to extract valuable insights out of our survey responses.

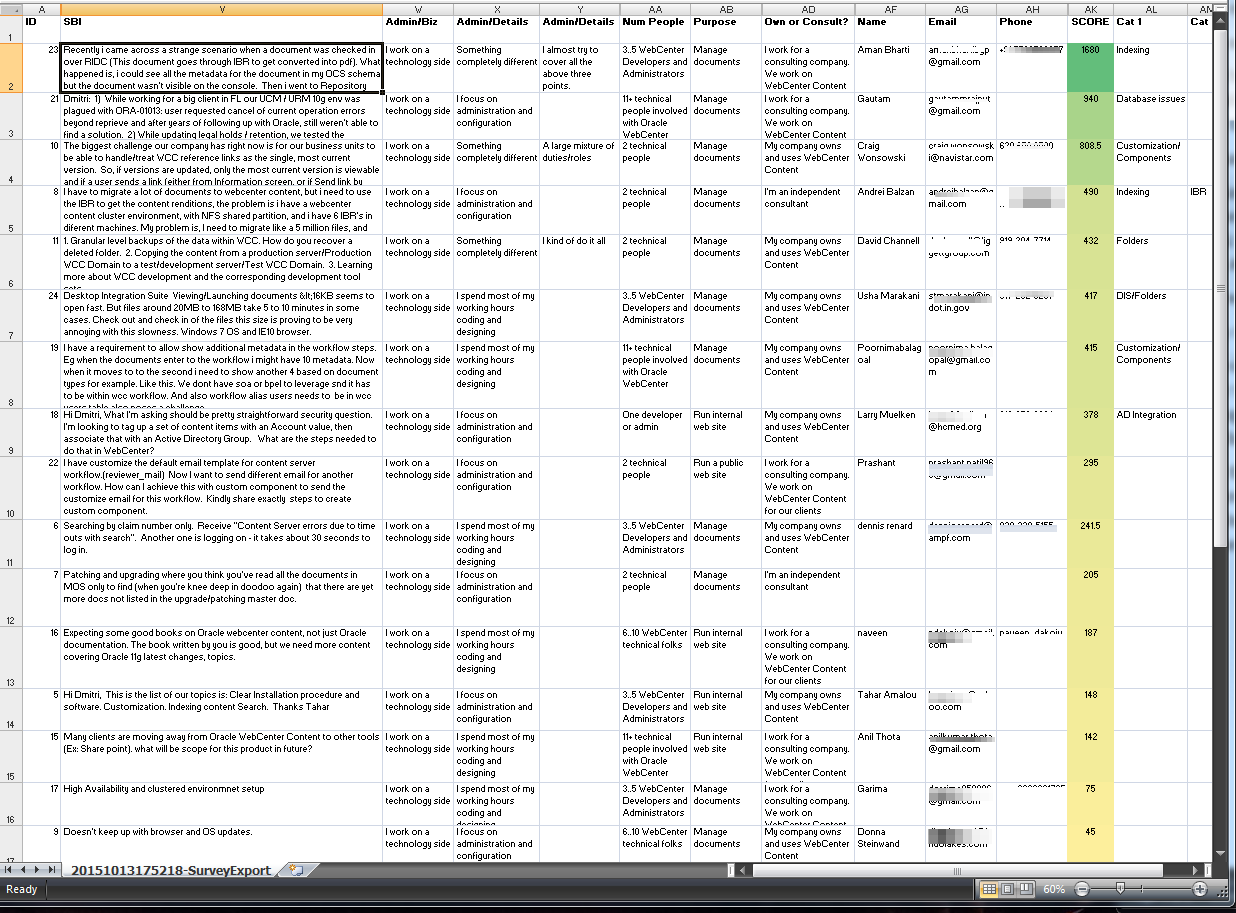

The screenshot below shows the export of the survey data with a few additional columns we have added in to analyze it:

We assigned higher score to responses where people spent more time describing their problem. We also bumped up the score for those who were willing to spend time with us on the phone to discuss their situation further. Once sorted by score, we then analyze their Single Biggest Issue (SBI) answer text for common problem categories (Cat 1, Cat 2 and on columns) and we take note of the language they’re using to describe them.

Today we call this ‘Interview Survey’ approach a BIB Survey – the Biggest Issue/Bucket Survey, as it helps to both, identify the biggest issues that our market or our business users are facing, identify which groups of users feel the strongest about solving their issues and also define ‘buckets’ – the frequent types of problems that people are looking to resolve.

Based on our stats so far, it takes about two minutes or less to process a single survey response. This makes it easy for a single user researcher to process a thousand BIB surveys in a single week, still leaving ample time left for a few follow up calls.

That said, all you really need to understand your market or your business users is a few hundred responses. The rule of thumb is this – as soon as you stop finding new types of problems in your Single Biggest Issue responses, your BIB stage is done.

We developed this BIB Survey tool based on ideas of Ryan Levesque’s1, the ultra-successful marketer and product developer, and we have been having great success with it, so I really hope I was able to communicate its value and made it easy for you to benefit and implement your own BIB Surveys in your organization.

Conclusion

There you have it. You now have a quick and flexible tool you can use to include all of your business users and all of your market in your user research. This will ensure that you never miss hidden critical insights that so many researchers today are just unable to discover.

We saw why it’s uber-important to gain maximum amount of insight about your users, and why observation and traditional surveys will not always bring you the results you need. We looked at the reasons why and how the new type of high performance interview-survey blend, the BIB Survey, can bring you this critical information, discover complete set of different problem types your users are facing and help you map these to demographic information, to make it easy to use this in subsequent analysis stage.

Will you be using them? Can you think of a specific scenario or a challenge that you can now solve with BIB surveys? Is anything missing? I’d love to hear your comments, your questions and your ideas in the comments area below.

1 Ryan Levesque. Ask: The Counterintuitive Online Formula to Discover Exactly What Your Customers Want to Buy…Create a Mass of Raving Fans…and Take Any Business to the Next Level: Dunham Books; 1st edition, April 21, 2015

Image of timer held in hand courtesy of Shutterstock.

Dmitri Khanine

Dmitri is a published author and frequent speaker at industry events. He loves to impress business users with six and seven figure savings by finding root causes and focusing project teams on solving the right problems quickly. At times not starting a project can be a wise and the most cost effective decision and Dmitri's User Research will provide hard facts to support the decision either way. Dmitri's 'secret sauce' is his ability to help organizations reduce the scope creep, costs and delivery times with better focused requirements and more efficient UIs.