A big part of UX research is talking to people and trying to understand how and why they behave in a certain way. So, several methods we use, like interviews and focus groups are in a way, amplified versions of face to face communication. UX researchers put a lot of effort into getting across a question just the right way and then understanding what the user is saying or doing. They tend to prepare for the sessions rigorously and go over the session recordings not only to uncover insight but also to reflect on their moderating skills.

But even though there are industry practices and protocols involved, at their core, usability sessions and interviews are observations and conversations you have with people to understand them. So, many things I have learned practicing user research are extremely useful in day-to-day conversations.

Really listen

Imagine you share something about yourself in a conversation. But instead of asking further or simply reassuring you to go on, the person’s reply makes it about them. Sounds familiar? Or are you the one who makes it all about them sometimes?

If you search for “conversational narcissism” online, you’ll find a lot of shaming for this behaviour. However, a study from Harvard University suggests that sharing information about yourself feels intrinsically rewarding. The study involved examining brain responses in a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner while people discussed their own opinions and personality traits. As they did so, parts of the brain activated that are generally associated with reward and pleasurable feelings. These are the same areas that light up in response to sex, cocaine, and good food, Adrian F. Ward explains an overview of the mentioned study.

But in fact, the same study found that similar neural activity occurred, when people were talking or thinking about themselves without any audience. So maybe we can improve our conversations with other people by having the most important ones with ourselves, through introspection. When you let go of the rush to think about “you” while listening to others, something unexpected happens.

In her wonderful book, Practical Empathy, researcher and author Indi Young calls to try a new way of listening that starts with shifting your attention back to your partner, every time it drifts:

You fall into a different brain state — calmer, because you have no stray thoughts blooming in your head — but intensely alert to what the other person is saying. /…/ You are completely engaged in a demanding and satisfying pursuit.

Indi Youg, Practical Empathy p. 50.

I certainly don’t achieve this level of concentration and flow with every user interview, but I’m getting better. And I’m sure this is a skill everyone can and should practice through simply noticing your own thoughts and redirecting attention to your subject of interest — the person sitting opposite. Listening actually is the first step towards real empathy.

Keep listening (that means stay silent)

There is an unwritten 90/10 rule in user research, meaning 90% of the talking should be done by the user (the one being interviewed). It took me some time to really take this on board. When you are engaged in listening and your partner goes silent you will want to encourage her, so remaining quiet feels counterintuitive. This is perfectly normal. But resisting this urge can eventually lead to better answers and a deeper conversation.

What happens during that pause after you ask a question and get a brief reply (or a non-answer) is that you both will feel an urge to fill the silence. If you resist to do so, your partner will either feel prompted to expand or will simply get that extra moment to reflect and consider what she might want to add. Remember that time moves slower when you are the one asking questions and speeds up when you’re answering.

Ask and echo

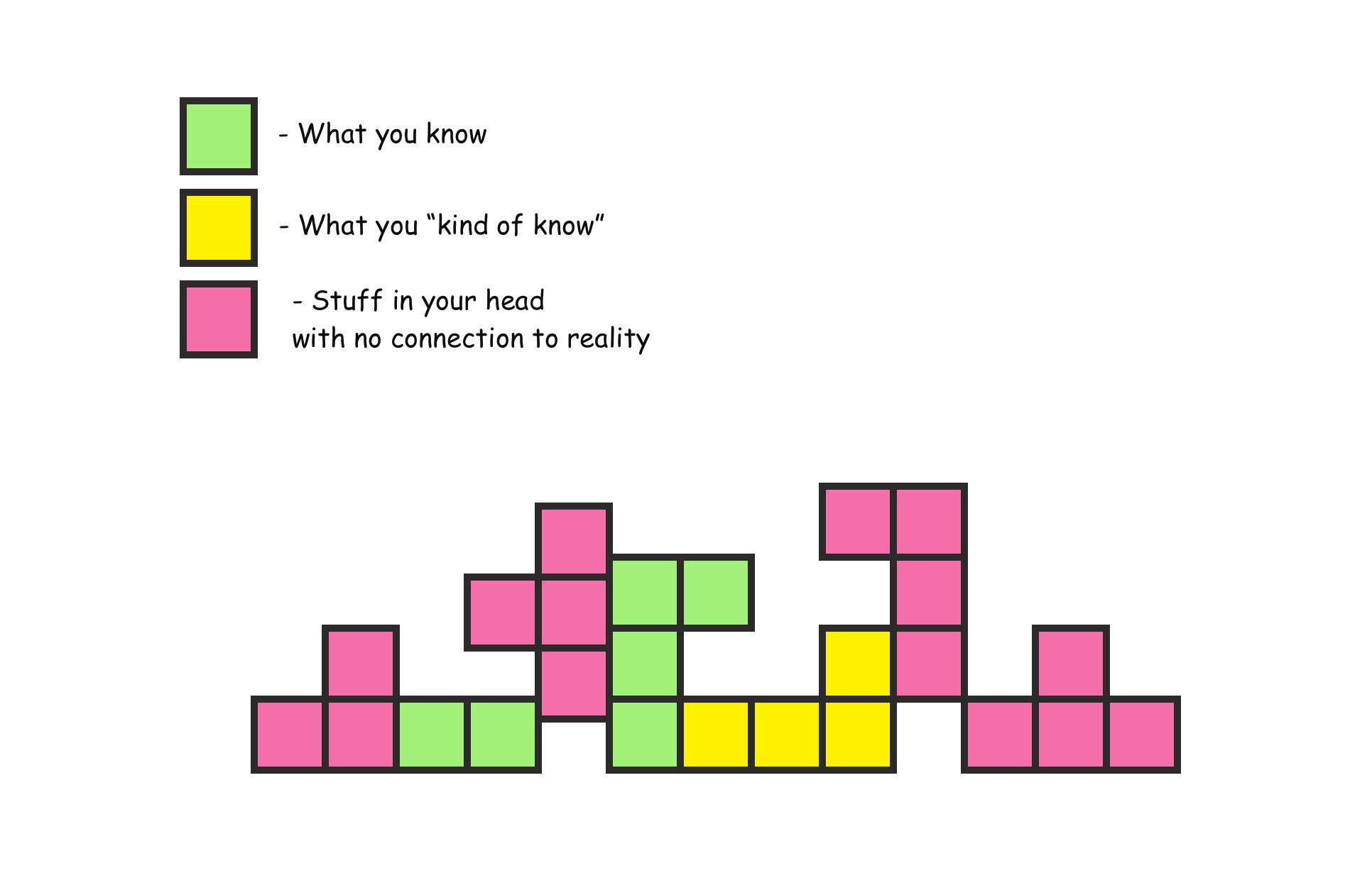

Now imagine you are listening to a presentation about a new concept/ project/ idea at work. She is using all the right words but… you don’t really get what she means. But no one else is saying anything so you keep quiet. First perhaps not to look stupid and then because you’re convinced you don’t care about the silly thing anyway.

People tend to fill the gaps between bits of “knowing” with assumptions that have little to do with what has been communicated. If you do that in a usability testing session and don’t follow up on a useful comment, it can result in poor decisions or no decisions at all (slowing down the design process). So UX researchers take pride in asking “dumb” questions. And as much as I’ve seen, it transcends beyond usability sessions, into work meetings and casual conversations.

During interviews I try to check in with myself and ask if I really understand what an utterance means and where it is “coming from”. If the answer is “not really”, there is a useful trick that might be helpful to anyone: Just repeat the last thing that was said and add your question. This avoids sounding offensive or putting new ideas on the table and helps to focus on clarifying what was said.

On final note, successful user research depends a lot on observation and reflection: learning how to keep attention present and reflect on what is happening around you and within — the two core skills we desperately need more of in any field and situation.