Chapter 1: The biased customer lifecycle

We are all consumers. We buy and use products and services, each of which has a life cycle for us spanning from purchase to useless. The way we consume has come a long way from the earliest beginnings, when consumption consisted of a crude transaction or debt: for example, exchanging the corn harvested in autumn for furs to keep the family warm in winter.

Nowadays we buy things on a whim, impulsively, to satisfy an emotional desire which has been constructed by influences embedded in a complicated social hierarchy. This hierarchy has evolved alongside the basic features of modern life such as money, markets, advertising, and its sole aim is to target and inspire consumers to buy the goods that have been created.

This evolution has created many jobs, a great deal of wealth and, you could argue, a certain purpose for the billions of people that now populate this planet. But it has its downside: occasionally and often in the long term, it fails.

The physical aftermath of our consumption of products can be seen in the problems of pollution. Plastic litters the oceans, we discuss the warming of the planet while ice melts. These are the bad outcomes from our consumption, the aftermath that we fail to capture before it leaks into the natural environment around us.

In the world of services the goods supplied are less tangible. They could be the healthcare you receive from a nurse, the plane ride you buy from a travel company or the money management carried out by your bank. Instead of physical waste, here the bad outcomes are less tangible: mis-selling in banking, lost pensions and locked-in gym membership.

Even less tangible are the bad outcomes from the new landscape of the world of digital. You can see examples in the software you have on your computer, the apps you download to your phone and the social media applications you use. The problems arising from this industry often get ignored as they are invisible, hidden on servers, and in your data that companies keep and use in ways that may well cause you anxiety in your daily life.

I see the problems that arise from these different areas of consumption as having the same source. Endings are no longer part of the overall consumer experience. We have moved the source of the problem away from the cause.

As consumers we are able to overlook endings. In business we have built a culture of ignoring them. As students we are taught they are not important. Endings are dodged and left for someone else to clear up. They are broken away from the rest of the experience.

It would be simplistic to assign blame. This is in fact a deep societal problem which has developed over hundreds of years. We have been programmed to ignore endings, to consider only the short term and to deny that endings need to happen.

We need to understand the position we now find ourselves in. It’s not enough to design better endings, although that would be an excellent start. It is about understanding the full significance of the position we are in: emotionally, environmentally, socially and commercially.

To do this is no small task, but I have attempted to put together the arguments, evidence and potential solutions for what I believe defines this enormous problem with endings.

The consumer lifecycle

The consumer lifecycle is a model used in marketing to define stages through which a person goes when purchasing and consuming something. For example, as a consumer you recognise you have a need to buy something. Maybe it’s more milk, or something more complicated like a new car, or to sign up to an Internet provider. Then you might look at some different options for where you are going to get this new purchase. Once you have decided, you then make the transaction, hand over the money, sign up and commit to the service. You then use the service or product until a point when it is not required. The science of this process can be reflected as a consumer lifecycle.

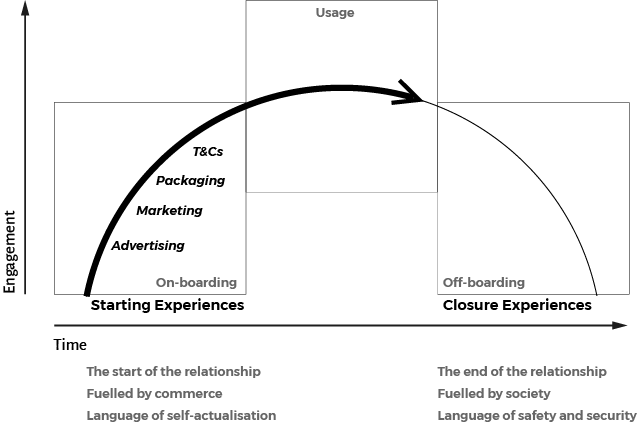

We will build on the consumer lifecycle and adopt a common vocabulary for the discussion in the book. To do this we’ll simplify the product or service lifecycle into three phases:

- On-boarding

- Usage

- Off-boarding

In this context, on-boarding is made up of starting experiences. These are the actions that persuade the customer to commit to the product or service: they form the start of the relationship between consumer and provider. Examples of starting experiences are advertising, that attracts you to a product or service, marketing that orientates you towards the decision to purchase, packaging that enhances the product and makes it look more attractive and Terms and Conditions that establish the agreement between provider and customer.

The usage phase completes tasks, empowers people and orders chaos. It is the stable committed relationship between the consumer and the service they use, or the product they own. Examples of usage experiences are paying into or drawing from a pension scheme, daily usage of a car or regular usage of an app.

Off-boarding is a less well-acknowledged part of the product or service lifecycle. It is made up of closure experiences of different kinds, such as the effort needed to neutralise the effect of the closure, to terminate the relationship between consumer and purchase. Typical closure experiences are the completion of a mortgage, the deletion of unwanted photos online, the appropriate disposal of an unwanted product, saying goodbye or closing unused accounts. Off-boarding acts to tidy up the impacts of consumption, and neutralise its ills.

The consumer awareness of endings

Sadly, most of industry ignores the ending as an important part of consumption. Although many producers make great efforts to counter the negative effects of consumption at an industrial level through legislation, improved materials and corporate governance, they are terrified of sharing, or even acknowledging endings with the consumer. Both producers and consumers have learnt to deny that endings happen.

Consequently we have all lost control of this part of the consumer relationship, which in turn removes our ability to deal with it sensibly. The product or service life cycle that has been created protects the consumer from questioning the consequences of consumption. A myth has been created for consumers that it is better to re-purchase rather than end the life cycle in a responsible manner

By failing to acknowledge the importance of dealing with endings we lose our ability to improve them. The beginning, or on-boarding, of a customer is now a complex ritual that, as consumers, we navigate confidently. But the ending of that process has been distanced from the consumer and is now almost invisible as part of the same experience. That distancing has also removed the consumer’s individual responsibility. This has had critical knock-on effects to the way we relate to the products and services that we consume, and is now haunting our ability to deal with personal and global issues.

The emotional imbalance

Our motivations and emotions at the beginning and the ending of the customer lifecycle vary. Not only do the tone of language and the source of the messages change, the emotions and motivations are quite different.

The examples above indicate that the sources of the messages associated with a closure experience often differ from those that coax the consumer to buy or join at the beginning of the product or service lifecycle.

The tone of off-boarding is also starkly different – an austerer, emotionless tone, desperately trying to demonstrate the impartial voice of authority in the black on white text that is often used. Whereas the voice of on-boarding is encouraging, full of joy, inviting our normal life to get better through colourful language, imagery and messages.

These messages speak to different motivations. The off-boarding asking for restraint, consideration and champions safety and security approaches, with a worrying tone of foreboding

The on-boarding encourages potential, tickling your dreams and fantasies with suggestions of how you can fulfil them and reach a level of self-actualisation.

We can illustrate this with the well used model of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Starting Experiences that facilitate the on-boarding of a customer answer, or at least propose to answer some of our strongest motivations – are represented by the arrow on the left. In contrast, Closure Experiences, that aid the off-boarding of a customer seek to spell out a far humbler set of motivations – indicated by the arrow on the right.

Differing voices

It’s very easy to spot the way in which the product lifecycle is biased by different messages by simply looking around you every day.

At the on-boarding phase of the product or service lifecycle we hear wonderful stories of how our lives could be improved by the purchase of a new product or service. But by the time of off-boarding we are made aware of the impact of our purchase and the damage this has on the wider environment.

The parties involved have different responsibilities and perceptions. At one end we have producers and advertisers that want to sell a product. Their responsibility is to the shareholders of the company to create a good turnover. At the other end we have governments and agencies who are responsible for safety and good practice on behalf of society.

Our empowerment is encouraged at one end of the process and derided at the other. For the consumer this is conflicting and overwhelming.

I will refer to these issues and models in the rest of the book as we analyse particular models to highlight the broken model underneath. We will look at examples from industry and how starting and ending experiences are used. We will also consider how these are communicated to customers throughout the consumer lifecycle.

We will start by considering the long history of endings.

If you want to read the whole book, it is available on Amazon from the 8th of June.