As UX designers, our role in our industry is more important today than ever. Our medium is maturing into a broad, multiple-platform, always on, multi-context, center-of-our-universe conduit for information. Our clients and customers are demanding more of us. We’re not just designing web experiences anymore. Our designs have to adapt and respond to a variety of devices with different input methods that are used under very different circumstances where user goals and expectations change as well.

As if that weren’t challenging enough, the technologies we use to build the things we design are becoming more sophisticated, more abstracted, more diverse, and as such, more difficult to keep pace with. But these emerging complexities of our industry are a good thing. They’re a telltale sign that our medium is growing up. The Web has become our global town square where culture bubbles up, revolutions are born, economies are nurtured, and our lives are lived.

We’re growing our teams to meet the needs of our medium too, and our roles continue to focus and specialize. Our mobile design teams are subdividing to address new platforms and devices. Content is no longer an afterthought in our process. We now have people for that, and they have a strategy. Our developers are changing, too, as they wrangle various flavors of databases, languages, and techniques that make our heads spin. And user science has its own fragmentation issues. We’re tackling information architecture, usability, and design often while communicating with clients, and the gamut of specialists in our team.

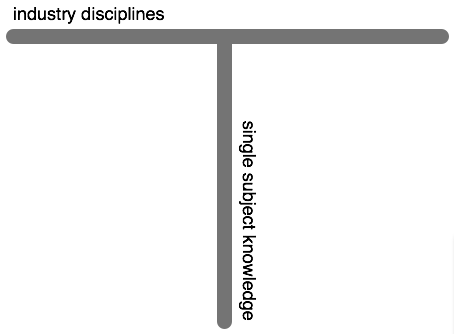

There’s a very good reason why good UX designers are hard to find right now. We have to know a lot. No, we’re not going to write an API, and maybe some of us won’t produce final design comps, but we have to know enough about all of these things and more in order to know they matter, and fit them together into a cohesive experience. UX designers need to have a T-shaped understanding of our medium (figure 1). The x-axis of the T represents a broad understanding of each sub-discipline. The y-axis represents a deep understanding of the user sciences.

UX designers need to have a broad understanding of the industry and deep knowledge of design.

A UX designer who can grasp the complexities of engineering problems, the subtlety of design, the power of great content, interaction design principles, and the value of a well considered taxonomy can properly navigate the challenges of a project that transcends platforms. But we have to grasp the big picture for another reason too.

The fragmentation of knowledge in our growing teams can lead to chaos, miscommunication, and ineffective design. We’re all spending a lot more time diving deep into our disciplines, and as we do, it’s harder to pop our heads up to see the landscape around us. That’s dangerous for our clients and our companies. Somebody has to peer into our separate silos and see the relationships to ensure a unified outcome. Someone has to be able to empathize with the people in our teams and help find user-centric solutions when silo blindness causes design, engineering, and content to collide. That’s where we come in.

Because we have to understand so much of what our peers do, and because empathy is at the core of our values, we are in a unique position to be the diplomats and translators within our fragmented teams. I’m finding that is a big part of my day-to-day work as the lead UX designer for MailChimp. In addition to designing wireframes, building prototypes, guiding user research, and writing code for the application interface, I spend my time talking to customer service about problems they’re seeing, then filtering and relaying those findings to developers. I work with developers to see final designs through, and listen to their suggestions that can improve the original designs. I collaborate with marketers, content producers, and other design teams to conceptualize branding and communication strategies for new features.

Language is at the heart of my work. I have to speak the languages of developers, designers, executives, marketers, content producers, and customer service experts. Each group has its own subtle nomenclature and motivations that aren’t always clear to others. That can lead to confusion, and sometimes even animosity. But with a broad knowledge of each group’s skills, a UX designer can often serve as a diplomatic intermediary, clearing up miscommunication while keeping user needs in the front of everyone’s mind.

I suspect I’m not the only one in our industry that is starting to find himself acting as translator and diplomat. These are roles that should come naturally to us. Our communication skills, inherent empathy for others, and grasp of the breadth of our medium make us a perfect fit. And how fortunate we are to be at the center of the lines of communication, as it empowers us to do our job more effectively. We get to see our designs change over the course of a project, and we can guide those changes to ensure they are made with the needs of users in mind, not because they take us down the easier path.

Our expanding presence in the project lifecycle does not make us project managers, though. Budgets, scheduling, and client management is a job unto itself. We’re simply the stewards of ideas, which can get compromised and mangled in a game of telephone as they are passed between team members. User experience is not only about seeing the big picture of how our applications and websites are used, but also about how they are made.

Along the way, it’s not uncommon for an interface to have features tacked on, new complexities introduced, and core areas get scoped out. It’s our job to stave off feature creep, and ensure that the team loops back around to complete the project as originally envisioned. That can be hard to pull off, but the real trick is doing it in a way that doesn’t alienate team members.

We’ve all seen our contributions to a project get crushed by the cogs of committee thinking. It stings, and demoralizes. It causes us to jealously guard our designs and turn a deaf ear to the suggestions from our teammates regardless of merit. This impulse can be as dangerous to your ideas as the threats from outside. While shepherding your designs to launch day, you have to remain open to the input of your colleagues. Not only will you find that your design will get better, but you’ll build up a stockpile of good will that you can cash in when you really need to call in favors to make sure the interface gets the extra TLC it requires. Diplomacy is your best tool to see your ideas to fruition, and cultivate a more rewarding career.

Diplomacy and communication skills are not easily learned from a book or a class, but if you’re a UX designer working in a team you’re probably getting the best education with these skills that you can. Spend some time outside of work getting to know more about your colleagues’ disciplines. Listen and empathize with the people you collaborate with as much as you do with the people you’re designing for. Though roles are splintering and technologies are becoming more complex, we can design more usable and enjoyable experiences for our users when we better understand our peers.